In the past four years or so, the Julia language has exploded in popularity amongst Data Scientists. Many of the Data Scientists who are now working in the Julia language have jumped to Julia after working with Python, which is lucky, as in a lot of ways, the syntax of both languages can be incredibly similar. Many Python programmers often make their first comment on Julia code " It looks like Python." That being said, a lot of these migrating Python programmers will not have much trouble getting used to the syntax of Julia.

While there certainly are many similarities between the syntax, methods, and key-words of Julia and Python, there are also some seriously large differences between the two. This slight variation could certainly create some headaches for Python programmers who are trying to effortlessly enter the world of Julia and take advantage of what the language has to offer without much strife. Luckily, the differences are quite minimal, and generally syntax is going to be quite similar!

Julia Syntax Basics

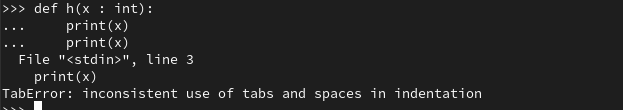

The first biggest difference between Julia and Python as far as syntax goes has to do with whitespace. In Julia, whitespace does absolutely nothing to the way that code is compiled. This is something I never really liked about Python; I always thought that using indentation as syntax was tedious. The language even implements an entire error, called a " TabError" for when you do this wrong.

This is certainly not my favorite part of writing Python, and although that is certainly just my preference I think many other Pythonistas would agree that this is not the best part of Python's syntax. Instead, Julia uses the end key-word, and that same function in Julia with inconsistent use of tabs and spaces in the indentation runs well in Julia.

function h(x::Integer)

print(x)

print(x)

endIf we wanted to, we could even move this print way over here, like this:

function h(x::Integer)

print(x)

print(x)

endIt really doesn't matter in Julia. One thing that does matter, however, is new lines. Creating a new line in Julia is like writing a semi-colon in JavaScript or C. That being said, adding a semi-colon to your code will have the same effect that it has in those languages.

function h(x::Int64)

print(x) print(x)

end

ERROR: syntax: "function" at REPL[10]:1 expected "end", got "print"

function h(x::Int64)

print(x); print(x)

end

h (generic function with 1 method)The semi-colon also does not do the same thing that it does in Python, which is hide the display of returns. Another substantial difference is also the annotations. In Julia, annotations are actually used for something other than documentation — that being multiple dispatch. When working in any scope below a global scope in Julia's Main, you can also annotate any type, and this actually helps with Julia performance. If you would like to read more information on that, here is an entire article I wrote about it:

Another key difference between the languages to identify is that both languages reside in completely different definitions of multi-paradigm. While Julia is quite unique, and uses multiple dispatch absurdity as a paradigm, Python is a little different in that it is an object-oriented scripting language with some generic programming concepts on top that make it multi-paradigm. This also has a significant impact on how constructors differ between the two languages.

Constructors

Pythonic contructors are very different to Julian constructors. Julia's constructors do have a surprising amount of similarities, however. In Python, a Constructor's " method" is called __init__(), and is put into the class and determines the arguments needed to construct the type. In Julia, however, an inner constructor is built, which is just a function of the same name of our struct that creates the type in some way. Another great thing about this in Julia is that we can also have multiple constructors for the same type. This makes things a lot easier, as now we do not need to write a bunch of extra methods to convert other data into the data to be provided to the __init__() method.

mutable struct Example

x::Int64

function Example()

new(x)

end

endWe can also pass types as parameters using {}, but this is a bit more advanced usage. This allows you to have a type with multiple different types under it, and then treat each type differently depending on what is inside of it. For example,

mutable struct Example{X}

x::X

function Example(i::Number)

new{typeof(i)}(x)

end

endNow we could construct one with a float and integer, and dispatch them accordingly like so:

x = Example(5)

y = Example(2.2)

myf(x::Example{Int64}) = println("it's an integer")

myf(x::Example{Float64}) = println("it's a float")Inheritance is also done in a different way in Julia. Rather than having classes inherit attributes and methods from other classes, the structs in Julia inherit methods from their abstract type. These do not have any values in particular, they are just a name that can be used to group multiple types together. This is done with the sub-type operator.

abstract type Dog end

mutable struct Poodle <: Dog

endNow all dispatches annotated to the type Dog will also be callable on the type Poodle.

Conditionals

Another area where Julia is slightly different, but quite similar is in conditionals. The first thing that changes is the operators and key-words. In order to get the inverse of a conditional, you use ~, rather than !. Instead of

if x ! in [5, 10]We would do

if ~(x in [5, 10])All that the ~ method really does is take a Bool and inverse it. Another different is also elif being elseif. Conditional statements are also ended with end.

if x == 1

println("it's one!")

elseif x == 2

println("it is two")

else

println("two is as high as I can count")Other than that, the operators are of course different. Two examples are the replacement of or and and with the operators || and &&. For a full list of Julia operators, you can view the Julia documentation on operators here:

Iteration

Julia also has iteration statements that are quite similar to Python. Probably the most substantial difference between Python and Julia in this regard is that when iterating multiple things a tuple must be provided. In Python, the following would be a normal usage of zip():

x = [5, 10, 15]

y = [5, 6, 7]

for i, w in zip(x, y):

passIn Julia however, the i and w above would need to be in a tuple.

x = [5, 10, 15]

y = [5, 6, 7]

for (i, w) in zip(x, y)

endJulia also has far more expressive comprehensions that can contain a lot more details on the actual returns for each element. If you would like to read a bit more on the abilities of Array comprehensions in Julia, I recently published an overview on it here.

Types

Another area where Julia differs slightly is in the construction of some types. Starting with a Julia-specific type, the Symbol is made by simply providing a colon before a phrase:

:mysymbYou can also make a symbol by using Symbol(::String), which is a Symbol constructor that takes a string.

Symbol("Hello there")Quotation marks are used for strings, apostrophes are used for chars. In Julia, these are two different types, so they are not interchangeable like they are in Python. Another type that is very different to create is the range type. This is actually something I really prefer in Julia to Python. In Julia, we can create a range simply using the colon:

for x in range(1, 5):

pass

for x in 1:5

endDictionary constructors are also a bit different, as they take a set of pairs, not whatever this is:

d = {"x" : [5,10], "y" : [15, 20]}Pairs are made with the pairing operator, =>, and are provided to a dictionary constructor directly to make a dictionary.

d = Dict(:x => [5, 10], :y => [5, 10])This creates a dictionary that is of type Dict{Symbol, Vector{Int64}}.

Common Methods

The last substantial difference is the common methods that are used in both languages. There are definitely some that end up being the same, such as the sum method. However, the len method becomes the length method, the max method becomes the maximum method, and so-forth.

x = [5, 10, 15, 20]

# python

max(x)

min(x)

len(x)

sum(x)

shape(x)

# julia

maximum(x)

minimum(x)

length(x)

sum(x)

size(x)A lot of the Python methods for a list, just as an example, are also a method of that class. In Julia, however, they are usually not — and any methods that alter the type are likely to end in an exclamation point.

# python

x.append(5)

# julia

append!(x, 5)

push!(x, 5)Creating methods is also very different in Julia. As we have looked a bit at different function structures prior, I will not dive into those differences. However, it is worth noting that Julia has both an operator for anonymous functions and candid support for syntactical expressions to make functions with very little code at all.

# Anonymous function

myf = arg -> println(arg)

domath(y::Int64) = y + 5 - 1The closest thing to these sorts of expressions in Python is probably lambda. If you are not familiar with lambda, it is certainly a great tool that Python developers should get familiar with, as it does have a lot of capabilities — especially in applications involving data. If you would like to read an article to get introduced to lambda, I luckily have written one which you can check out:

Julia is a language that certainly deserves its spot in the Data Science and general-purpose programming ecosystems. That being said, it is understandable why those working in Python might want to try out Julia for the first time and not really no where to start. Hopefully this small cheat sheet helps some Python developers out on getting started with Julia! Thank you for reading my article, and I hope this has been helpful towards bringing Julia programming into your Data Science toolbox!