In the 1600s London was a mostly filthy, overcrowded city. It was much, much smaller than the massive conurbation that it has developed into today. Streets were narrow, and rickety wooden buildings were packed into these alleyways, with progressive building upwards and outwards. If you looked above your head on some streets, it would be hard or impossible to see the sky, because the upper levels of buildings would meet above your head, blocking your view. The situation was so dire that in 1666 a spark from a small bakery would trigger a massive five day long fire which destroyed over one third of all buildings in the city. Remarkably, fewer than ten people actually lost their lives. It was plague, not fire, that was the great leveller of 17th century London.

The Great Plague of 1665

Having first arrived on British shores in 1348 as the Black Death, killing as much as half the population at that time, the plague had returned frequently, and the Great Plague of 1665 killed approximately one-quarter of London's population within a year. A pathogen carried by fleas that lived on black rats, the flea would often jump to a human when its host died. One bite and within days the egg-sized swellings or buboles that developed in the armpits were a sign that your days were likely numbered. Soon this progressed to vomiting and diarrhoea, followed by bleeding from the skin and nervous spasms. In a minority of cases, if the buboles popped and produced a foul smelling ooze, you had some small chance of surviving, but otherwise you were dead within days.

With pathogens and vectors still undiscovered at the time, there were many proposed causes of the plague. 'Bad air' caused by the pervasive stink of open sewers was one. A quarter of a million dogs and cats were destroyed because animals were believed to be carriers — sadly these were the wrong animals. If you were a Catholic, it was God's punishment for allowing your faith to lapse, and if you were a Protestant, it was God's punishment for not completely eliminating Catholicism. If you were an astrologer — hugely popular at the time and practiced by all sorts — it was all about how the planets aligned. If you really had no idea, you could always put your trust in a quack to sell you some tincture or a Cordial Balm of Gilead to help protect you.

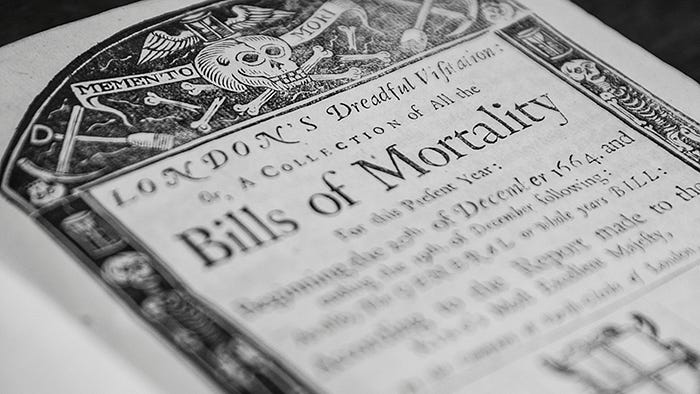

Bills of Mortality

As you might imagine, public record keeping was not great at this time, and before the late 1500s, deaths could only be traced to those who could be found in the burial records of church parishes, but with no information about cause. It would not be until 1837 that formal registration of deaths would be made compulsory in Britain, but in 1592 the London authorities started tracking the causes of death via weekly published documents called Bills of Mortality, and these offer fascinating insights into the wide variety of surprising and mysteriously-named ailments that sent Londoners to their graves. Let's take a look at a Bill of Mortality from the year of the Great Plague.

There's some fascinating information in this document. The scale of the plague in London is clear, with well over half the total deaths attributed to it. And if this document is to be trusted (which is a big caveat), then London's murder rate of 1 in a week is hard to separate from the same statistic in the modern era — in some ways the city hasn't changed all that much. The recording of those who were 'christened' also reminds us of the deeply pervasive Christian beliefs of the time, with many believing that unbaptized souls would never set eyes on the pearly gates of heaven.

But what are some of these weird and mysterious causes of death like Kingsevil, Rising of the Lights, Flux or Impostume? It is important to read these in the context of the lack of understanding of pathology at the time — the cause of plague, for example, would not be discovered for another two centuries. At this time, medicine was very much 'say what you see'. Many of these causes of death described symptoms that the unfortunate soul displayed just prior to their expiry — Griping in the Guts is one example. Let's look at a few interesting or surprising causes on this list.

- Kingsevil: Kingsevil was scrofula, a tuberculosis of the lymph nodes — a deadly disease at the time, but today eminently curable via antibiotics. The name at the time came from a popularly held belief that it could be cured by the touch of royalty. This custom originated from the turn of the first millennium and was first practiced by King Edward the Confessor (c 1003–1066). By the 17th century this belief was at its peak, with King Charles II said to have touched almost 100,000 victims in his lifetime. It was to continue in England until the reign of Queen Anne the following century, and continued in France until the early 19th century.

- Rising of the Lights: The 'lights' in this case referred to the lungs, and this was a general term for any deaths that seemed to be associated with violent coughing or obstructions to breathing. This could really have been anything, but medical historians believe it is most likely to have been what we know today as croup.

- Frighted: Most likely this was a death resulting from some sort of nervous shock — possibly bringing on a cardiac arrest. Such deaths are exceptionally rare, and there is a good chance that this death was misreported.

- Imposthume: This is a pus-filled cyst — enough said.

- Chrisomes: Infant mortality was very high in these days, and chrisomes were babies who died within their first month, around the time they would be baptized. Baptized babies wore a white cloth on their head known as a chrisom, which gave rise to this term.

- Dropsie: This was a term used to describe subcutaneous swelling, known today as edema. Often these were people suffering from congestive heart failure.

- Flux: Also described as bloody flux, this is what is known today as dysentery. The state of sanitation and drinking water in London at the time makes it surprising that so few such deaths are recorded.

- Rickets: We still call this disease rickets and it is a disease caused by a deficiency of Vitamin D. It's extremely rare today, but 23 deaths in a week from rickets tells us that life in London was pretty miserable for most, with low levels of sunlight exposure and a poor diet. Because Vitamin D has a role in calcium absorption, the most common visible symptoms of rickets were stunted growth and skeletal deformities such as bowed legs or a misshaped, protuding chest.

- Scowring: This was also dystentery, and its not clear why it was recorded as a separate cause of death. Interestingly this term is still used in rural areas of Britain and Ireland — my uncle who raced greyhounds for a living often described his animals as suffering from the scour.

- Sote Legge: It's unclear what this is, but it could refer to gangrenous legs or feet which is a late stage symptom of diabetes.

- Spotted Fever/Purples: This described a feverish condition accompanied by purple spots and may have been meningitis.

- Starved at Nurse: This described a baby that would not take to its mother's breast. Nowadays this would be commonly described as failure to thrive.

- Stones: This describes kidney stones or gall bladder stones. Surgery for these conditions was available in London at the time, but with no antibiotics on the scene, many risked death from surgery because the pain from these conditions was so unbearable. Among those Londoners of the time who had surgery for stones was the famous diarist Samuel Pepys.

- Strangury: This described painful urination, often caused by bladder problems or a sexually transmitted infection. At a later point, such infections would be described as French Pox, just in case there was any doubt about the debauchery that went on across the English Channel!

- Surfeit: This described a death from excess — at this time it usually referred to obesity or alcoholism.

- Teeth: Although rare and extreme cases of poor dental health could lead to infections that were fatal, this most likely describes infants who apparently 'died from teething'. This is a little bit of a medical mystery, but here 113 children in a week are recorded as having died from this. This correlates with contemporaneous accounts — the Scottish physician James Arbuthnot wrote in 1732: "Above one-tenth part of all children die in teething (some of them from gangrene)". One possibility here is that some of the remedies encouraged to relieve the pain of teething may have caused infection, for example the use of dirty wet rags for the child to chew on.

- Tissick: This was a death associated with coughing or some sort of lung disease

- Winde: This was a death associated with abdominal inflammation or pain.

- Wormes: These deaths were attributed to a parasite of some form.

Bills of Mortality would continue to be published until the early 19th century when they were replaced by statistics that came from the statutory General Register of Births, Marriages and Deaths, and many examples of Bills of Mortality can be found online. They represent an extremely valuable source for professional and amateur historians in helping us understand a critical period in the history of London and the social and scientific development of England and Great Britain.

What are your observations from this article and the Bill of Mortality? Feel free to comment!