In the chapter "The Mystery of the Origin and Tradition of Daitō-ryū" in Matsuda Ryūchi's "Secret Japanese Martial Arts" (1978), there is the following description:

5. While it is a traditional custom in Japanese martial arts to give names to martial arts techniques according to their characteristics and purpose, in [Takeda] Sōkaku's time there were still no names for the techniques (Note 1).

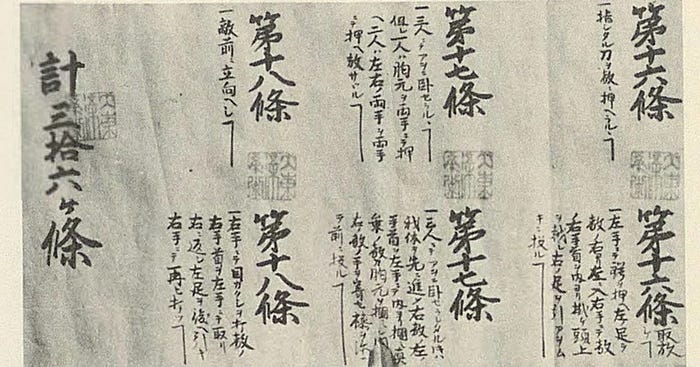

For example, the first technique in the scroll, "Daitō-ryū Jūjutsu Hiden Mokuroku" (大東流柔術秘伝目録, Catalog of Secrets of Daitō-ryū Jūjutsu), the first scroll awarded to a practitioner, is described as follows:

Article 1. Strike with your right [hand]. Article 1. Lift up the opponent's elbow with your left [hand] and turn the opponent's wrist to the right with your right [hand].

The first article 1 shows the movement of uke (受, attacker) and the second article 1 shows the movement of tori (取, defender). Thus, in the Daitō-ryū scrolls (catalogs), there are no technique names (kata names), and the techniques are generally listed as a set of two movements, one for the attacker and one for the defender, as in the first article, second article, and third article …

In general, there is no other kobudō (ancient martial arts) school except Daitō-ryū that writes its techniques in the form of articles on scrolls like this. In addition, it is common practice not to include explanations of techniques in catalogs.

For example, in the "Omote no kata" (表の形, front forms) section of the "Jin Maki" (人巻, human scroll) scroll of Kitō-ryū, one of the original schools of Kōdōkan Judo, only the names of the techniques are written as follows:

Body, dreaming, force-avoidance, water wheel, water stream, pulling down, falling down, smashing, valley fall, wheel fall, helmet-taking, helmet return, evening shower, waterfall fall (体、夢中、力避、水車、水流、曳落、虚倒、打砕、谷落、車倒、錣取、錣返、夕立、滝落)

These techniques are still passed down in judo under the name "Koshiki no Kata" (ancient forms).

Looking at the names of the techniques of Kitō-ryū, we see not only technical characteristics, but also names that evoke scenery, such as "water wheel," "water stream," and "evening shower." These characteristics can also be seen in other schools. In other words, the names of the techniques are based on the beautiful scenery of nature, or words from Japanese and Chinese classics are used in the names. This is not only because of the fear that easy-to-understand names might lead to the theft of techniques, but also because of the effort to express the prestige of the style, its spirit, and the profundity of its thought by giving elegant names to the techniques.

If Daitō-ryū is a "palace martial art" (殿中武術) that the feudal lord of the Aizu domain had decreed "not to be taught at all except to senior vassals of 600 koku or more and attendants for fear of its being leaked to other domains" (Note 3), then naturally the style of the scroll and the names of the techniques described on it must also be of prestigious quality. If so, writing the techniques in the form of articles gives a somewhat strange impression.

Note: 1 Koku (石) means 150 kg of rice. During the Edo period, the stipend of Japanese samurai was calculated in koku. 600 koku is currently approximately 45 million yen.

Generally, a samurai who received a stipend of 100 koku or more was considered a senior samurai. According to the Daitō-ryū claim, Daitō-ryū was only taught to vassals of 600 koku or more. There were only about 30 to 40 such vassals in the Aizu domain. When teaching such senior vassals, teaching methods naturally had to be based on a respect for formalities.

However, Takeda Sōkaku was not only uninterested in the names of the techniques (kata), but also in the kata themselves.

I have written previously about the fact that the techniques he taught at the Osaka Asahi Newspaper were not according to the scrolls, and his student, Sagawa Yukiyoshi, also describes Takeda's view of the scrolls as follows:

Questioner: Some people think that if they get a diploma (scroll), that's all there is to it. Sagawa: A scroll is just a piece of paper. What is important is this body. What is important is how much of the techniques have been absorbed into the body. Takeda Sensei used to say, "Scrolls are written inaccurately," and I never even looked at them (Note 4).

Sagawa also describes the techniques of Takeda's Ono-ha Ittō-ryū [swordsmanship] as follows:

Questioner: I have heard that Takeda Sensei also studied Ono-ha Ittō-ryū. Sagawa: I have heard that he attended the dojo of Shibuya Tōma in Aizu Bange Town. Sensei's sword is creative and a synthesis of many things into a unique technique. It is not a kata, but a realistic, hands-on style, and he taught what was appropriate for each situation (Note 5).

Perhaps Takeda had a negative, if not contemptuous, view of kata, or formalized techniques. If you stick to kata, you will not be able to use it in battle. Therefore, he did not teach according to the scrolls, and he may not have been particular about the fact that the kata did not have names.

But even so, if Daitō-ryū has a history of several hundred years, as it claims, it is unnatural that none of the successive masters invented names for their techniques during that time.

Moreover, even if Takeda learned a certain jūjutsu practiced at the Aizu domain and created Daitō-ryū based on it, the techniques of the original school must have had names.

In Okinawan karate, there were originally names for single kata such as Naihanchi, Sanchin, and Seisan, but kumite kata, or yakusoku kumite (pre-arranged kumite), did not exist, nor did the individual techniques have names. The earliest example of yakusoku kumite was made by Hanashiro Chōmo in 1905 for middle school students. Therefore, in 1879, when Takeda is said to have traveled to Okinawa, yakusoku kumite did not yet exist.

Motobu Udundī's torite (tuitī in Okinawan dialect) was also taught in the form of semi-free kumite, not yakusoku kumite. Although torite has basic technique names such as oshi-te, ogami-te, and koneri-te, there was no formalized yakusoku kumite or individual technique names contained within it.

Moreover, in the days of Motobu Chōyū, the way torite was practiced was that he would say to the uke (attacker), "Now, come on," and let the attacker attack, while the tori (defender) was free to perform a different technique each time. This teaching method is somewhat similar to Takeda's teaching method in his seminars.

Takeda also taught different techniques one after another, never repeating the same technique more than once in the seminar. Therefore, most of the participants could not learn the techniques properly.

Motobu Chōyū's teaching method was to apply a different technique each time, as in the demonstration by Uehara Seikichi in the video above. The following is a poem about Motobu Chōyū's teachings.

形(かたち)ととのりば技や色あして 技の身につきば形失せて

If a martial art (technique) is formalized, the true technique will fade away. True techniques that have been mastered are integrated into the body and cannot be preserved as a form.

The philosophy of Motobu Chōyū has something in common with that of Takeda Sōkaku. Of course, in the case of Motobu Udundī, the idea is valid because it was originally a martial art of "isshi sōden" (一子相伝), where the father taught only to his son. Since it was difficult for Daitō-ryū to maintain the prewar teaching methods, after the war, the teaching methods were systematized in each lineage. Therefore, Takeda Sōkaku and the current Daitō-ryū philosophy may not be the same.

Isshi sōden: In some traditional Japanese arts and martial arts schools, there was a tradition that the real (secret) techniques were taught by the father to his son or only one disciple.

Motobu Chōyū did not allow Uehara Seikichi to apply techniques to himself, and Uehara Seikichi learned them by being applied to him. Takeda also never allowed his students to apply techniques on him when he taught them (Note 6).

In the case of Motobu Chōyū, it may be because he was of aji (royalty) status and thought it would be impolite to take his hand and apply the technique. In Takeda's case, it seems to have been out of precaution that a student might grab his arm and break its bones.

Some have pointed to the influence of swordsmanship in Takeda Sōkaku's unique teaching method, but if he really trained in the martial arts in Okinawa, as has been said, we should consider the influence of "Okinawa-te" as well.

Also, Okinawan martial arts are not armored martial arts, but bare-skin martial arts. In the past, people practiced literally with their upper bodies naked.

While there are other features of Daitō-ryū scrolls that are not found in other schools, there are also points that seem to be based on the forms of other schools.

In the following, I will discuss some of the points that have been pointed out in the past and points that I have newly noticed.

The following can be read in a paid article (in Japanese) on note.

Thank you for reading my story. If you would like, please follow me.