WARNING: This story is an updated, revised and corrected version of a previous story. Racist and bigoted language, racial slurs, race violence prevalent.

A September, 2019, New York Times story headlined "The Last of the Dunk Tank Clowns" pronounces the gasping demise of the dunking booth, a one-time staple of carnivals and state fairs across the United States. In it, fair-goers paid a couple dollars to hurl three baseballs at a dinner plate-size target that would drop an insult-spewing clown into a tank of lukewarm water.

This attraction is now virtually obsolete. Outdoor Amusement Business Association president Greg Chiecko was quoted as claiming he polled his members about dunk tank clowns and that "most say they don't know of any that still exist today."

Maria Calico, president of the International Association of Fairs & Expositions, claimed she has seen an insult clown only "once or twice in the last decade."

In today's progressive society, no one wants be disrespected about their hair, clothing or weight as an inducement to drop a trash-talking Bozo into the tank. Recognizing this trend years ago, the clowns' humor became much tamer, and some of the few games remaining even displayed disclaimers that fair-goers were about to encounter "satire humor" or an "insult zone," and that the management was "not responsible for insults made by the clown."

The clown dunking booth's history, however, is far more savagely dark than canned insults foiled by simple political correctness. It is in fact rooted in a most vicious form of white supremacy.

The African Dodger

In 1881 an enterprising carnival promoter in Indiana got the idea to chain a monkey to a table and invite people to pay a couple pennies to try to strike the primate with three balls. The game, however, was a failure, as there seemed to be almost universal indignation at the use of "an innocent creature" for such blood-sport.

"For any man to put an animal in this position, it is a shame and an outrage," howled the September 23 Indiana Herald. "It is nothing less than a severe case of cruelty to animals, and as such should be prohibited by the management of the grounds."

Stung by the criticism, the promoter reinvented the game by replacing the monkey with an unemployed black man who placed his head through a hole in a piece of jungle scene-decorated canvas stretched between two poles. He called his new game "The African Dodger," and it became a national sensation.

As a target for baseballs, the monkey was off-limits, but the recently-emancipated black man was fair game.

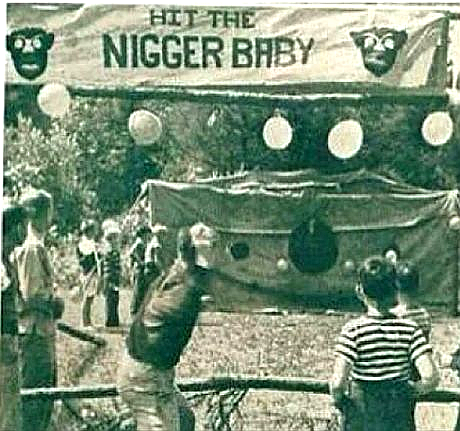

The African Dodger — also known by more racially contemptible labels as "Kill the Coon," "Hit the Coon," "Nigger in the Hole" and "Hit the Nigger" — showed up on American carnival midways just as lynchings and Jim Crow segregation became more widespread. And while it may be natural to assume this was a distinctively southern game, it actually had no geographical boundaries, with ads and clippings for it showing up not just in the Deep South but in Boston, New York, Scranton (Pennsylvania), Rutland (Vermont), even Dodge City (Kansas).

The game was an epitome of violent race subjugation, just falling short of actual lynching. As if segregation and such blatantly racist criminal justice inequities as "black codes," in which black men in many southern states were arrested and imprisoned for sometimes nonsense crimes, were not bad enough, the added indignity of a black man having to support himself and a family by allowing middle-class white men to satisfy bloodlust toward them by hurling baseballs, with the specific intention of injury or even death, is particularly appalling.

Many sociologists at the time went out of their way to justify the game by reminding the white power structure that blacks really didn't mind such humiliations. Scientists, religious leaders and politicians all agreed that the African was "less evolved," and had "heavy and massive craniums" that resisted such punishment. All these fallacies served to further dehumanize the black race, to render them unworthy of empathetic or humane treatment and convince whites it was not only acceptable but challenging and fun to brutalize them.

The Museum of Jim Crow Memorabilia at Ferris State University in Big Rapids, Michigan, states that "With everyday objects, forms of entertainment, advertising and public policies confirming this [supremacist] hierarchy, it is possible to see how whites came to believe they were superior, and how some blacks could internalize these images, practices, attitudes and policies and come to see themselves as inferior and to accept the role of target."

Mode of operation

"The modus operandi was as follows:" stated an account of the African Dodger game in the August 30, 1888 Nebraska State Journal, "The manager would sell the privilege of throwing three balls at the colored gentleman's cranium for 5 cents, or 6 for 10 cents. When you threw the balls at the darky it was his business to dodge them. [A] small boy then bought the balls back to the manager."

"The manager was shouting in a loud voice, 'Here you are gentlemen; three balls for five or six for ten. Come now, kill the coon; kill him I say! Hit his head once and you get one cigar, twice and you get two cigars, three times and you get half a dollar."

The unnamed writer related his own unsuccessful efforts before graphically describing how two young men laughingly broke the rules by throwing balls at the same time, to the amusement of the manager and those watching, but with violent and shocking results to the dodger.

"They raised their arms to throw, when whiff!! Bang!! — one ball caught the darky on the ear, and the other on the top of his head … [the darky] became so confused that he didn't know enough to take his head out of the hole. Each threw their remaining five balls in rapid succession, and while some of them missed the darky's head, yet enough of them hit him to give him a swelled eye and the [blood] began to flow. You should have heard the crowd shout. How they did cheer! And I felt glad, as I had a grudge against that darky."

Swallowing pride

An answer as to how torturing and brutalizing a race of people became midway entertainment lies with the propensity of post-Civil War American Caucasians continuing to relegate blacks to lower-class, even sub-human status, affording them impunity to continue acts of white superiority over them.

Only a few years earlier, in 1875, Texas Physician E. T. Easley and Howard University Educator Edward Ballock had written that blacks were not just "ill-equipped" for any social status, but that they had a "lessened sensibility" at their nervous systems, making them better equipped to endure pain. In Chicago, Dr. Charles Bacon wrote around 1903 that education and social integration for blacks was "as out of place as a piano in a Hottentot's tent," and that blacks were "just as devoid of ethical sentiment or consciousness as the fly or the maggot."

One clipping that appeared in a Bel Air, Maryland paper on October 16, 1885, gleefully recalled that the African dodger at a sideshow "was mistaken by a youthful disciple of Darwin for a big monkey." Another item from a 1920 Delaware paper even referred to the dodger not as a man, but as an "it" — "Baseball experts will try their best to crack the woolly nut of the famous Black African Dodger as it grins at them through a hole in the canvas …"

"A coal black son of a warmer clime shows a row of gleaming white teeth while throngs of men and boys strive unsuccessfully to land a baseball squarely on the tip of his nose," proclaimed a 1923 Rutland (Vermont) Daily Herald.

Many today may question the willingness of black men to endure such ritual pain and humiliation, but well-paying employment opportunities for black men between 1880 and the Great Depression of the 1930s were mostly nonexistent, and generally confined to low-paying manual labor, manufacturing and farming jobs. Working as an African Dodger — with the prospect of earning $5 per day plus expenses over a two- or three-day period — may have made the admittedly reprehensible job a risk worth taking.

"First colored gentleman — Mornin' Mr. Johnsing. What are you doin' now, whitewashing?

Second colored gentleman — No sah. I've left the field of manual labor, sah, and am now earnin' my living by head work, sah.

F.C.G. — So? Preachin'?

S.C.G. — No; I' the African dodger at the shootin' gallery, sah."

— joke published in the May 21, 1889 Dodge City Journal Democrat.

"internal injuries which may prove fatal."

Serious injuries in this game were prevalent, especially when a "ringer," such as a minor league or even pro baseball pitcher stepped up to try his luck. One incident described in the August 13, 1908 South Dakota Citizen-Republic was how a "crack twirler" of the Norwalk, Connecticut, baseball club named Joseph Dest initially chucked two softballs to "throw the dodger [Walter Smith] off guard." He then intentionally blasted "a terrific drive" straight into the man's mouth with such force that "several of the dodger's teeth were knocked out, and the ball locked so securely within the colored man's mouth it had to be cut to pieces before it could be removed."

In 1898 the Waterbury (Connecticut) Journal reported that a dodger named William Kelley was so gravely injured by numerous curve balls thrown by Chicago pro ballplayers at the Chutes at Hartford that he had to be taken to the hospital by ambulance. "Other professional players practiced throwing at him, and as a consequence he has been out of the business for a week or more … it was said at the hospital that his face was like a puff ball and that his eyes were badly swollen."

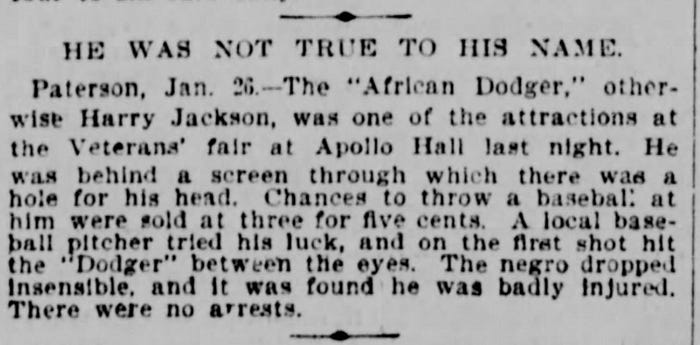

A January 1896 New York Tribune story boasted that a local baseball pitcher on the first shot drilled a dodger named Harry Jackson "right between the eyes," knocking him unconscious and leaving him "badly injured."

A 1908 Hanover Pennsylvania news article concluded that a "squad of local baseball players" repeatedly battered a dodger named William White. "The players were enabled to throw straight and hard, and they hit the coon nearly every time."

"After a half-dozen pitchers had thrown in rapid succession, the negro was pretty well used up, and he was compelled to retire soon afterward with internal injuries which may prove fatal."

Baseball legend Ty Cobb was reported in the June 2, 1911, Washington Times as searching out the African Dodger game first upon his covert arrival at Glen Echo Park. After striking the dodger seven times in a row, his identity was revealed, and he was offered 10 cigars. No word on the condition of the dodger after taking seven straight Ty Cobb fastballs.

Two dodgers were reported to be killed by strikes in New Jersey in 1924, but full documentation is lacking. One Boston dodger named Benjamin Atler was found dead floating in the harbor. It was not known if his death was an accident, a suicide or the result of his employment.

"Unworthy of civilization"

While most saw nothing wrong with brutalizing black men instead of monkeys, there were still smatterings of protest toward the game throughout its heyday. A 1913 editorial in the Joliet, Indiana Evening News spoke out against it, albeit in a backhanded manner by repeating the time-worn stereotype of black' alleged abilities to withstand pain:

There is little to say in favor of it. One can scarcely defend the encouragement it gives to the human mind to 'soak' a few balls at that ebony head … Probably the African dodger himself has little feeling in the matter. The distance is deceiving; the average aim is not over accurate; he has some inches to dodge and he is seldom hit. And when he is it doesn't appear that the balls inflict any hurt or injury on the proverbial solid negro skull.

The editorial went on to correctly state that the game was more of a statement of the lynch mob mentality of the throwers than the dodgers. "The impulse to hit the darky is akin to that which that creates the blood lust in the mob. It is a dormant savage instinct — the same which causes a boy to torture a cat or an Indian to grill his prisoner at the stake. It is altogether unworthy of civilization."

That savagery became more pronounced when managers encouraged (or even paid bonuses to) their dodgers to trash-talk the throwers. Being catcalled by a black man at that time was the ultimate insult to a white, and in his anger, he tended to purchase more and more balls as his throws got more and more errant. The July 3, 1895 New York Sun reported that a "stolid-looking German was throwing himself red in the face in his vain efforts to hit" the fast-talking "coon dodger" at a local fair.

Why, yo' ole fahmer,' commented the target, 'yo' ain't no good. Too high there, hi-yi-yi! Yo' clo's don't fit yo'. I know yo're tailor in Hoboken. That's the ideah! Hit me in the head! Hit me! Yo' can't do it, yo' Hoboken farmer!

"The man who was throwing the balls didn't like the [insulting] and he got angry. That was what the negro wanted. His throwing became wilder, and he finally gave it up after offering to punch the negro's head."

Revenge was indeed sometimes served by some who had failed to clobber the fast-talking black man with baseballs. Records indicate some were so angered they threw rocks, even a hammer at the dodger after their turns.

The game also was not just seen at carnivals and fairs. At a 1908 Elks Lodge Jubilee in Washington D.C., the "visiting Elks were royally entertained" as "nigger babies" were "hit with baseballs until they were unable to maintain their upright position …" Also, that year a table-top "African Dodger" children's game was introduced at Bloomingdale's that featured a "grinning darky" with the words "Hit the Dodger! Knock Him Out! Every Time You Hit Sambo the Bell Rings."

Northern aversion, Southern persistence

Around 1910, fair managers in the Northeast began replacing the African Dodger with a prototype dunking game called the "African Dips." Then in 1915 New York became the first state to pass a law prohibiting the African Dodger, with a fine of $50 and up to one year in prison for both the manager and, incredibly, the black man working as the dodger.

In November of that year, Massachusetts passed a more sweeping law, which included a $500 fine and three years' imprisonment for "any person who engages or manages in any form of show which would hold up to ridicule and disgrace any member of any race, sect, color or religion."

In 1923 a Scranton, Pennsylvania manager tried to soften the original game by replacing baseballs with rotten eggs.

Unsurprisingly, the original African Dodger game remained wildly popular in the South. A particularly disparaging article in the August 21, 1923, Miami News described how the game — called "Nigger-in-the-hole" — was to be one of the main features at the Redland Fair that year. Organizer J. M. Bauer and his partner H. E Schumaker, said that this attraction, "is time-worn… but never fails to draw a crowd."

"We are importing a real live nigger from Liber-hot-tot, where the natives are skilled in the art of dodging coconuts thrown at them by monkeys who sit in the trees and aim at them as they pass," barked Bauer. His stated goal was to "reduce to a minimum the number of cigars and sticks of chewing gum that he will have to hand out to the ones making the lucky hits."

Better off dead

By the beginning of World War II, all these versions had coalesced into the more familiar dunking booth game, with the black man replaced by a wisecracking clown in a final racial affront that was not at all coincidental. But even with the original game thankfully defunct, by the late 1940s, some war-weary southern white people were already pining for the good old days of whizzing baseballs at black men's heads. A 1947 article in the Longview, Texas News-Journal reported nostalgically that "The fun loving spirit of the American people shows up in scenes along the midways and side shows. One familiar example has been the African Dodger, the colored gentleman who thrusts his head through a hole in the curtain and challenges the crowd to hit him with a baseball. So with its showing of high achievement, its pleasant social meetings, and its fun and frolic, the county fair tells a lot about American character."

Indeed, it does.

Postscript

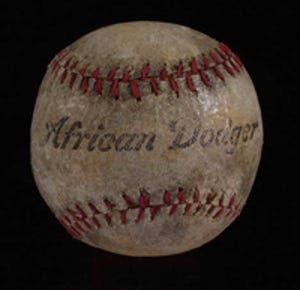

On August 31, 2001, Leland's sports memorabilia auction house sold an "African Dodger" baseball for $349.33, mistakenly describing it as a "1930s African Dodgers Negro League Baseball."

###

Read more "American Grotesk" stories at www.dalebrumfield.net.

-