Welcome back to Autistic Advice, a semi-regular advice column where I respond to reader questions about neurodiversity, accessibility, disability justice, and self-advocacy from my perspective as an Autistic psychologist. You can submit questions or suggest future entries in the series via my Tumblr ask box, linked here.

Today's question comes from two separate Tumblr users, both of whom want advice for balancing their commitment to organizing and community-building with their need for a lot of alone time as Autistic people:

This is a question that really hits me where I live. Figuring out how to balance the need to connect to others and enact my political ideals in my behavior with my need for bountiful alone time and rest is an ongoing question for me, one that I've had to develop answers to numerous times through my years as an activist (and then as someone who stopped identifying as an activist).

I have struggled to find belonging within most politically engaged activist communities that I have joined over the years. So many of the campaigns I joined in my youth overworked me, manipulated me into committing to efforts that did not suit my strengths, misunderstood my mannerisms and quietness, punished me for expressing questions or divergent opinions, and made no space for someone who lacks emotional empathy and processes in a very slow, cold, analytic way. My alienation in activist spaces (and the burnout that such overwork caused) was so extreme that for a while, I said I did not believe in community at all.

My attitudes are quite different now that I've actively created the social bonds with other neuro-weird, queer anarchist types that I always needed, and have received their care, understanding, and patience. I surround myself with people whose political perspectives I respect and value, who are forever learning and evolving in their outlooks, and who welcome open discussion when they disagree with me. These are people who truly live community by offering up spare guests rooms, spare change, free rides, home-cooked meals, and compassionate ears to those they love — and who don't view one another's efforts with a knee-jerk attitude of suspicion and insufficiency.

Today, I would say that my political activist life and community-building efforts are in the healthiest place they've ever been. I am dedicated to the cause of Palestinian liberation, and show up to protests and other organizing events around once per week. I'm also plugged into a lot of unionization efforts throughout my neighborhood, on campus, at local Starbucks locations, and at the local queer clinic, Howard Brown, just to name a few.

I am more conscious than ever about making time for the people I have built relationships with — because "communities" are just relationships, and we must nourish them ourselves with our actions if we wish to reap their benefits. When someone gets fired, street harassed, kicked out of an apartment, or otherwise fucked over by oppressive systems, I'm able to be by their side with a free meal or some mutual aid money and a distraction for the day. I've had to make real sacrifices in my career to be able to do that, but my friends are worth the world.

I finally feel that I'm free to decide for myself what the right course of action is when an injustice is presented to me, rather than drowning in overwhelm or allowing some charismatic nonprofit leader to point me in the direction that best suits their own ends. I've been on the streets for months and yet I still feel energized. There's a calm clarity to the work I do now that allows plenty of room for relaxation, and at last I've granted myself permission to speak up when an initiative doesn't make sense or a community meeting isn't accessible for someone like me.

I remember how terrible it felt to alternate frenetically between over-committing and burning myself out on the one hand, and dropping into despondency and inaction on the other. The balance I've finally been able to strike is something I wish I could gift to every other socially conscious Autistic person that I know. But since I can't, and since the solution to this tension will look different for everyone, what I've done instead is collect advice from a variety of neurodivergent organizers, interview a few trusted colleagues, and mined my own experiences to create the following tips:

Keep Unnecessary Meetings to a Minimum

"Don't attend unnecessary meetings," advises Jersey, an Autistic activist in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Jersey has been on the front lines of numerous pro-Palestinian actions in the past several months, serving as a medic during the #BlocktheBoat action to delay the shipment of munitions to Israel, shutting down the Oakland Federal Building, and blocking the Bay Bridge, an action for which he was arrested and charged with false imprisonment (among other laughable charges) by the San Franciso District Attorney. Since the siege on Gaza began in October of last year, Jersey has been living and breathing for the Palestinian cause. Yet even he has limits.

"Tell [fellow organizers] that your capacity for meeting, especially in real life, is low," he says. Instead of having to speak at length with organizers about your interest in getting involved, see if you can articulate your own role within the movement. That way, you won't have to be "managed" as much.

"For example, if you're a photographer, tell people that and then demonstrate that you can show up relatively independently, take great photos, and then show them with the group," he says. Once you have proven yourself to be reliable and competent, you can skip meetings without facing as much criticism.

Many organizing spaces are oriented around neuro-conformist standards of what socializing and planning for an event must look like. Non-Autistic people generally process new information socially as part of an ongoing dialogue, whereas many Autistics prefer receiving all the relevant facts in a single, linear document they can read and process on their own. Many activists also enter a movement with intense emotional needs, and wish for others to bear witness to their suffering and share how they are feeling too. This means that those of us who find socializing and emotional processing to be draining will have to advocate for ourselves.

"We can remind organizations to be intentional about what does and does not have to be a meeting," says Aeryn, another organizer. "Sometimes all you really need is an online survey, a memo, or a thread where people can ask questions online."

If you can, tell meeting organizers that you are unavailable to meet often, but that you will listen to meeting recordings or read the agenda on your own time, and then communicate through email or private message to indicate that you have. Depending on how much you trust an organization and its leadership, you can either explain directly that you cannot process information in real-time easily because of your disability, or you can simply say you're busy with school, work, or family obligations.

Operating independently may require being strategic in the roles you take on within an organization. Jersey says: "If you've never done security but want to do security, you will have to do a lot of training and meeting with people. But if you're already a trained medic and have some type of credential… you can probably just tap into a medic chat and sign up for events as they arise." This, in fact, is what he's done.

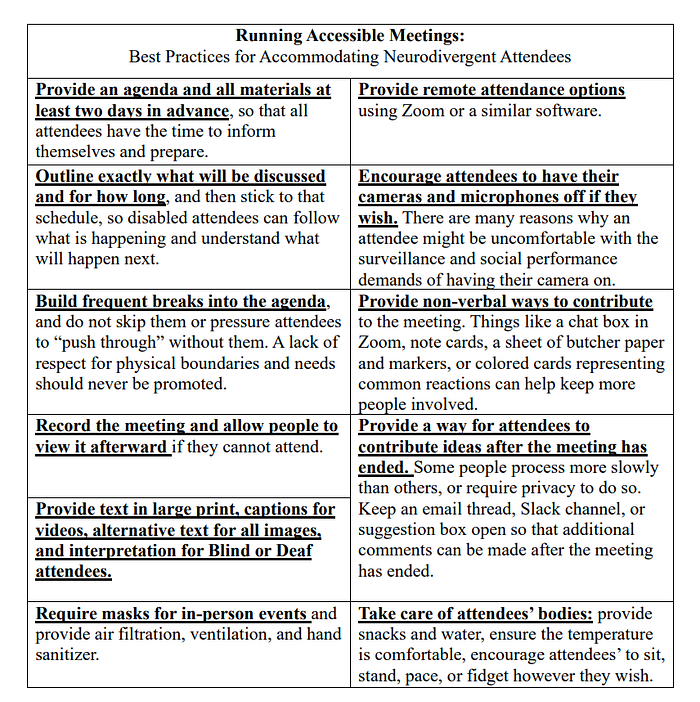

Of course, it will be sometimes be necessary to get to know other members of your organization of choice, express your own perspectives to the group, and receive updates through some form of meeting. However, there are still many accommodations you can request to make those meetings more accessible:

Push for Accessible Meetings

When an activist movement is new or its resources are limited, its meetings may tend to be urgent, somewhat disorganized affairs, rife with lots of thinking out loud and amorphous brainstorming and possessing little in the way of an agenda.

Autistic people typically find it very hard to contribute to such meetings, because the flow of conversation is unpredictable and confusing, and most of us struggle with knowing when it's appropriate to jump in and offer a comment. The constant flux in conversation topics is exhausting for us to keep up with, as are all the social and emotional undercurrents bubbling beneath what's actually being said.

After the meeting is over, we may have almost no recollection of what was shared, because we were putting so much energy into masking and wearing our "listening faces." Critiques and questions may occur to us hours after the discussion has ended, after we've had some time alone to digest and reflect. Even if we are physically present within a space, we are pervasively excluded when meetings are conducted in such an unstructured, overwhelming way.

Thankfully, all of this can be avoided. Here are some of the accommodations that organizing meetings should provide in order to maximize their accessibility — not just for the sake of Autistics, but for anyone who struggles to process verbal information quickly and form their own immediate verbal responses to it on the fly:

"At in-person meetings, I am so stressed by trying to seem normal and freaking out about potential COVID exposure that it's virtually useless for me to even be there," share Dave, an activist in his 40s. "I have demanded that all my anti-racist church group holds all meetings online, and many others have thanked me for pushing for that.

Another organizer, Cherry, says that she had to push for her union's meetings to include a clear agenda of speakers. "I need defined roles to know how to contribute, and I can be a strong problem solver if I know I'm welcome to be. Now in our meetings there is a time set aside for people to ask practical questions. That is when I roll up my sleeves and say okay, if we want to have a potluck, I know what to do, and I need x, y, and z to do it." She says that if she wasn't explicitly given a chance to hold the floor by a leader, she would simply be silent.

There is truly no need for a meeting to ever be run in a chaotic, structureless way — it harms absolutely everyone and limits an organization's potential. When necessary materials and a meeting agenda are not sent out well enough in advance, everyone is left scrambling to play catch-up.

When discussion is open to whomever speaks up the most quickly and with the loudest voice, the most privileged individuals in the room tend to dominate. Providing nonverbal and asynchronous ways to contribute to the conversation makes it easier for those with developmental disabilities or who are less fluent in the language being spoken to remain involved. And as COVID continues to ravage our healthcare system, there's no excuse to not provide remote means of attendance.

If you are new to an organization (or to activism in general), you might be afraid to push for such changes. But keep in mind that you are doing a wide, diverse array of other people a service when you do so, and improving the strength of the organization as a whole. You can point to the guidelines published by the Autistic Self-Advocacy Network or Make Things Accessible to help bolster your argument, or ask leadership to read this piece.

And remember that asking organizations to accommodate you is an important litmus test: if you are infantilized, ignored, spoken over, and treated as if you are being an obtrusive "pain" for making such requests, that tells you a whole lot about whom the group prioritizes and who is likely to be left out repeatedly. If the overall vibe of the community sucks, hit da bricks. You can find (or create) something better. No political cause on the planet is best served through suffering and exclusion. Compassionate coalition-building is necessary for all of us to thrive.

Tell Organizers When Something Isn't Working

One time a few years ago, I was attending an in-person training for a racial justice organization that I had been involved with for quite some time. An external speaker was visiting to share with us about her time protesting white supremacist hate movements on the East Coast and to assist us in planning our own actions, but before diving into her programming, she wanted us all to engage in a little informal ice-breaker activity.

"What I'd like for you to do is stand up and wander around the room, and find the first person whom you naturally make eye contact with," she instructed, "And then sit down with them and ask them some of the following questions about their racial identity and background…" She listed the questions out verbally and then told us to get started.

Everyone in the room rose to their feet and my heart immediately began thudding. Chairs were pushed back, bodies began moving throughout the space, and voices raised in laughter, but I was unable to do a thing. I was transported back to every gym class or school project where I had been last picked. I couldn't bring myself to raise my gaze or grant anyone eye contact, and didn't even know really how one was supposed to go about doing so in the first place. Looking at someone in the face was never "natural" to me, and others seldom paid me any attention even when I did.

I knew I wasn't supposed to find my conversation partner as quickly as possible, latching onto the first body that came near me, and that rather I was supposed to roam. Yet as I started to roam, I saw others breaking off into pairs and turning away from me. It was like I was a ghost. There was some gentle, inexplicable dance to looking at others that I couldn't understand, and everyone around me joined together into a mysterious blur. On the verge of tears, I ran to the bathroom and locked myself in a stall for fifteen minutes, waiting for the activity to end.

This casual, relatively unstructured activity was meant to "break the ice" but all it did was freeze me. I was made acutely aware of my difference, and made so terrified of exposure that I beat a hasty retreat. Later, I wrote an email to the event's leader, letting her know that for Autistic people like me, it is often impossible to naturally, effortlessly make eye contact with some unknown person and then approach them. I miss out entirely on the signals that other people's bodies and faces give off that allow them to coordinate such an activity.

I would have been far more comfortable if a discussion partner had been assigned to me, I explained. However, many other neurodivergent people would find the entire self-reflection activity to be mortifying regardless. I recommended that she provide clear guidelines in the future for how individuals might partner up, and ensure that everyone in attendance had access to reflection questions ahead of time so they could prepare.

Part of me also wished to ask why a lengthy reflection on one's personal racial identity journey was necessary for organizing a protest of a racist security firm, which was what we had actually gathered there to do, but I held my tongue on that point. I knew that for many people who are not Autistic, building familiarity through conversation appears to be essential. I'd much rather get to the point of the gathering. But I understand there must be some middle ground.

Thankfully, the organization had a significant neurodivergent membership, and the event lead had worked in churches for many years, where she had grown somewhat accustomed to accommodating people with disabilities. She apologized to me for the awkwardness of the encounter without any defensiveness, and said she'd work on getting better at including neurodivergent people. On the whole, I felt good about the interaction.

Sometime later, the leader of that same organization pushed for all of its members to sell tickets to a fundraising gala. "Everyone should aim to get at least five people to go to this event," he told us, passing event flyers into our hands. "Talk about this gala with your coworkers. Talk about it with your friends. Have a buddy over for a drink and then ask them if you can count on them to attend. We need to really push this."

I bristled once again. I didn't understand why it was important for us to focus so much on raising tons of money, and in particular, I didn't think inviting friends to an expensive, fancy dinner event was an especially good fit for my skills. I wouldn't enjoy schmoozing and networking at such an event, nor would anyone I knew. I didn't feel comfortable speaking up in that instance, though, because the pressure was so strong.

It was becoming clear to me by then that the organization's goals had diverged from what mattered most to me. Instead of directly confronting racist institutions and protesting discriminatory policies, as this group had once done, it was now becoming the fundraising arm of the leader's campaign for elected office. I left the group shortly after.

I share both of these anecdotes as an illustration of how important it is for us Autistic activists to speak up about our viewpoints and explain to our fellow organizers when things are not working for us. In the best of circumstances, other activists will want to include us, but are ignorant about our needs. Many conscientious people really will make the necessary adjustments once we explain to them that we can't provide eye contact, make phone calls, donate much money, or participate in team-building skits.

In the worst of cases, we have the freedom to become noncompliant and simply walk away. Activist work is done on a voluntary basis, after all, and so it should always reflect our deep-seated beliefs as well as what's best for us. I have done activist work with many organizations that eventually proved to be too moderate or too focused on short-term electoral outcomes for my tastes. I'm too much of an anarchist to want to contribute much to any one person's political campaign. I'm too Autistic to be knocking on doors and attending galas. But there are plenty of other valuable things that I can do, ones that align more with both my needs and my understanding of how change really happens.

Attend Events That Don't Require Much Socializing

There are plenty of ways to get involved in a movement, even in person, that don't require sitting through tedious meetings and performative small-talk. Showing up to these can help foster a sense of belonging and breed familiarity without zapping your social and emotional batteries so much.

"Attend something like art and banner making [events], where there's people around but no need to engage so much," Jersey suggests. Many abolitionist groups also hold letter- and postcard-writing sessions, for instance, where you can gather around in relative silence with other people and draft missives for prisoners without any need for eye contact or chatting.

Protests, rallies, car caravans, and other demonstrations are also a natural fit for those of us who can handle the bustle of crowds but don't find unstructured conversation to be comfortable. Part of the reason that I remain so motivated after months of Palestinian liberation actions is that many of the events I've attended have been downright fun for me rather than a slog. I enjoy chanting and clapping along with the rhythm of the drums and marching up and down Michigan Avenue in a big crowd of people. Hell, I often fork over $25 for the privilege of moving around in a noisy crowd at the dance club!

For me, it's a delight to be among thousands of other people who share my values, but without the burden of having to speak. Protests help me to feel less alone and despairing, and plug me back into the great potential of the collective despite living in a world that is woefully individualistic. And as someone who has to use their communication abilities as part of their "job" all day long, it's refreshing for me to be able to stand in a crowd and feel that my physical presence is enough.

There are all kinds of ways to be engaged in your community that rely upon acts of service and presence rather than speech and socializing. Do you care about poverty and hunger? Then consider joining a soup kitchen, food pantry, or Food Not Bombs chapter. You can spend your free time filling bowls or liberating wasted meals from dumpsters instead of attending meetings. Have a knack for keeping things clean? Help your local organizing office get its files in order or volunteer to assist elders in cleaning their homes.

Community gardens, park districts, refugee centers, homeless shelters, needle exchanges, night ministries, queer community centers, YMCAs, and more are desperately in need of people like you, no matter what you have to contribute. And rolling up your sleeves to do the unglamorous work of keeping an organization running will make people appreciate you, and that can help you build greater belonging and closeness.

"If you're there reliably doing the dishes and stacking the chairs, people will respect you immensely," says T, an anarchist with over thirty years of organizing experience. "Lots of people are all talk, or only want to do the work that's exciting, like going to blows with the cops. But the ones who keep everyone fed and the space clean and maintain the library? Those are the ones who keep us going."

T's advice brings us to the next essential component of remaining engaged healthily as an Autistic activist: identifying which unique skills and gifts you have to lend to a movement, and letting that guide your efforts rather than panic or guilt:

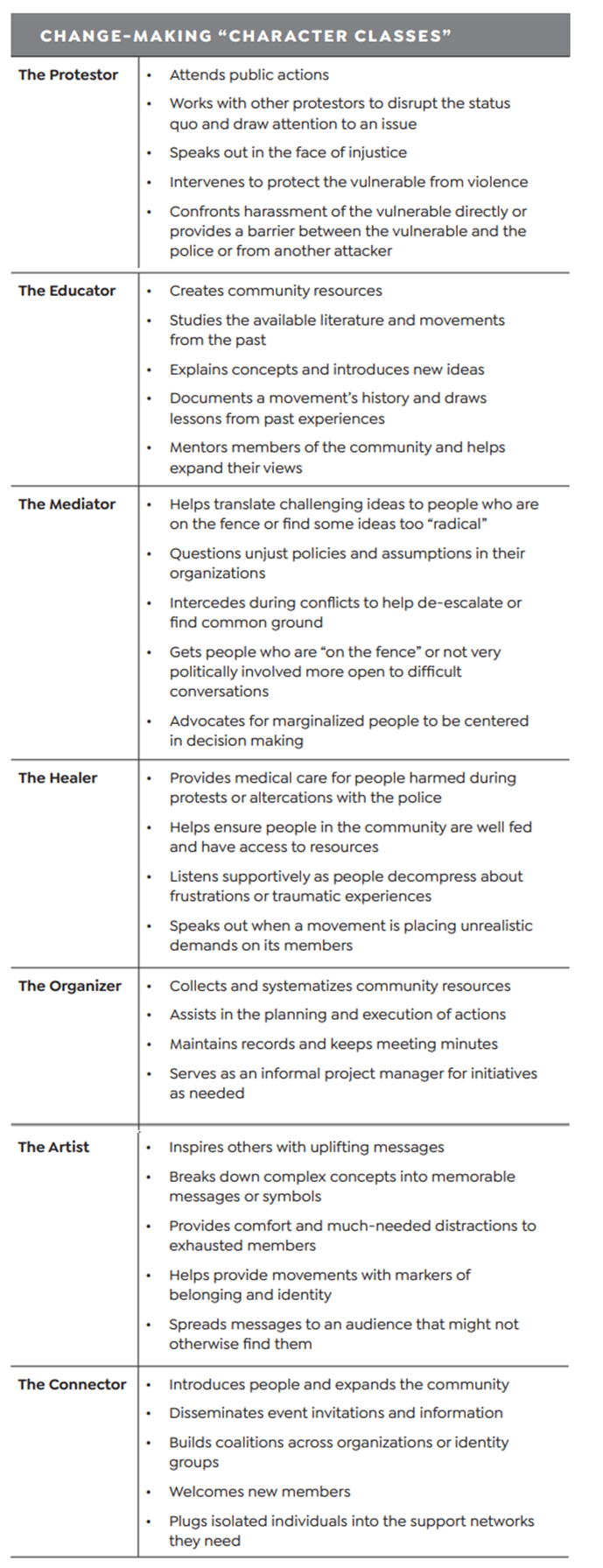

Figure Out Your Activist "Character Class"

Not everyone is suited to be a Black Bloc protestor in heavy boots and a bandana with a makeshift riot shield by their side. Some Autistics and other neurodivergent folks revel in the excitement, physical engagement, and pathological demand avoidance of breaking laws and destroying property, of course, but others among us lack the muscle tone and reaction times to ever be useful to the movement in that way.

With time, nearly all of us will migrate from the kingdom of the well into the kingdom of the sick, and that's if we ever held a passport to the well kingdom in the first place. Thanks to repeated bouts with burnout and long COVID, fewer and fewer of us are capable of doing the most physically grueling of activism. That doesn't mean there isn't a place for us in the movement, however. In fact, each one of us arrives with a distinct constellation of experiences, perspectives, and skills that can be useful — and rewarding for us to use.

In my newest book, Unlearning Shame, I speak about the importance of finding one's own activist character class. We are all familiar with the figure of the protestor, but we can make just as much of a difference if we are a healer, an artist, or a connector of other people, too. Here's a table from Unlearning Shame summarizing what some of the most common activist character classes are:

Of course in reality, the possibilities are limitless. As T says, one of the most significant yet quiet contributors to his local anarchist scene is a research librarian who joined the movement after finishing graduate school. "She saw our heap of files and immediately recognized that we had a lot of valuable information there," he explains. "Ancient zines, books that have been out of print for decades, notes from meetings scrawled on a napkin. And she forced our mess into a coherent organizational system."

Another Autistic activist that I spoke to told me that he took his passion for information security and used it to help other organizers better protect their identities and keep the police from discovering their plans for upcoming actions. He is most comfortable interacting with others remotely, and has served as an informal consultant to numerous leftist groups across the globe.

I want to make it clear that special interests don't have to be particularly technical to be useful to an activist movement. One Autistic ADHDer that I spoke to, Norman, has a passion for animated shows like Bluey and Steven Universe, and that helps him connect with other activists' kids. "Whenever a big crowd gets together I volunteer to do the babysitting, and that's much easier for me," he says. The parents in his community are deeply appreciative of his efforts, which frees them up to do more of the work that matches their own character classes.

Leveraging a special interest or area of professional expertise into your activist work can be very helpful for Autistics who can't (or don't want to) meet with politicians or make endless phone calls. We should also find ways to lend whatever privileges we possess to the movements we believe in, too. This can be as simple as speaking up in favor of the graduate student union when one enjoys the protections of being a professor, for instance, or fighting to have racial justice issues taken more seriously by your employer if you are white.

Not all of the meaningful political action that we do will occur under the guidance of a formal activist organization — we have to be on the lookout for chances to bend or break unjust rules at our jobs, for conflicts on our streets that we can de-escalate, and for sympathetic neighbors who could be made into more lasting comrades and members of our community. Some of this work is inherently social in nature, but it needn't be as exhausting as going to regular DSA meetings. Sometimes it's as simple as holding a single conversation — or starting an apartment-wide Slack chat:

Build Community in Small, Sustainable Ways

My apartment complex has been hit with a series of thefts recently. My housemate's bike was stolen, as was one of their packages and one of mine. One neighbor's expensive textbook was stolen, and another had multiple packages of miniature figurines lifted. Normally, this is the kind of situation that inspires renters to email their management company angrily, put up some security cameras, eye their neighbors with suspicion, and maybe even call the cops. Thankfully, one of my neighbors decided to take a different path:

"I think someone from outside of the building is coming in and taking our packages," read a note taped to our front door. "It is hard for any of us to do anything about these thefts when we don't even know what one another look like. Tomorrow at 7pm it's supposed to be fairly warm out. Would anyone like to meet outside and discuss this problem? If so, write your name and apartment number here." By the time I discovered it, five other residents had already written down that they were interested in meeting to discuss the problem.

After gathering together to make introductions, my neighbor offered to create a group chat that allowed us to all communicate about future stolen packages and other happenings in the building. It may sound like a small thing, but by choosing connection over isolation, my neighbor helped to make our shared home into a more mutually supportive and open space. One of my other neighbors has emotional outbursts in the hallway sometimes, and every single one of us has been too fearful to do anything about it until now. But now that the walls between us are starting to erode, it feels more possible to check in and really show up for one another.

If we truly wish for the world around us to change, then our activism must be a daily practice. If we wish to vanquish systemic racism, homophobia, violent imperialism, profound social isolation, and exploitative capitalism, we will have to dramatically reorient nearly everything about our lives. But such a task is daunting, especially if you already struggle to connect with others because of a disability that is widely stigmatized.

I know that I believe in a more community-oriented world, but I still avert my eyes from most of the people I pass on the street because I'm either tired or afraid of what they might say to me. I have to consciously make the choice to offer a smile, to say "hello," and to push myself to volunteer for the annual weeding & cleaning of the plaza on my corner.

I know these efforts are worth it, because they have made me feel more loved and safe, and helped me realize that even my smallest efforts can have meaning when combined with the work of everyone else. But encouraging myself to take part in them is a constant struggle against forces that would have me believe that I am freakish and unwanted and that the only security I'll ever know is from staying locked away and alone.

As Autistic people (or other neuro-weird folks), we don't have to do our community-building typically. We can still bond deeply with others even if we do it in a slower, quieter, more roundabout way. One union representative that I spoke with named Dione told me that they have done nearly all their organizing work over the messaging application, Discord.

"I added a ton of my coworkers at the warehouse on Discord and made a vent channel so people could share what all they were going through," they say. "There's only so much rabble-rousing you can get away with doing at work out loud, but in a private server, people feel more bold. We drafted a letter together to give to management using that app. I used that app to do a straw poll of where people were leaning on the union vote. It's spared me so many meetings and phone calls!"

"Start a coworker group chat on Signal!" recommends another organizer, who messaged me anonymously. Signal is an encrypted messaging app. "I have done so much organizing with it!" I can vouch for it as well — I have used it to plan actions that could not be spoken about in a public venue.

Building up stronger, more authentic connections to the people around us is an act of powerful political organizing unto itself. On our own, our actions hold very little sway. But together, in the hundreds and thousands? We can block a bridge, smash up a weapon's manufacturer's windows, drain a corporation's coffers with our boycotts, and yell so passionately outside our elected officials' doors that they never get a moment to sleep. As a collective we can stay fed, and housed, and feel less broken — we can be seen in all our messy diversity and accepted as complex living beings rather than just means to a productive end.

But most of us are very, very far from knowing true collectivity these days, particularly in the industrialized west. The upshot of this is that every time we choose to open up to others, we are taking a step in the direction of the radical and the liberatory. As an Autistic person who used to struggle to speak to other human beings at all, it's important that I remind myself of that. Every single greeting that I offer, every new name that I learn, and every moment where I choose to get a little vulnerable with a stranger at the bus stop matters, and is an act of creating a better world. I don't have to be innately good at it or have endless energy for it. I just have to do it the best that I can.

And the rest of the time? Well, I get to rest!

Rest and Recuperate — and Let Others Carry Your Work Forward

"I plan ahead before going to a protest," says Jazmyn, a member of Students for Justice in Palestine on a campus in the Midwest. "I bring a snack and something to drink, I have a friend come with me, I wear noise-cancelling headphones, and I plan in lots of toilet breaks. And then I make sure to take the rest of the day off afterward."

Numerous neurodivergent activists that I interviewed for this piece emphasized the importance of budgeting one's time and energy carefully. Several different people shared with me that in the past, they used to overestimate their abilities and overcommit to far more actions than they really could sustain — often because they didn't know how to reject requests from pushy or panicked fellow organizers. But experience has forced many disabled organizers to learn their genuine limits.

"I keep the whole next day clear [after a protest]," says Dave. "I have long COVID from pushing myself to do too much when I was sick. I won't make that mistake again."

"I had to stop doing Black Bloc actions because of an injury to my shoulder from when a cop slammed me to the concrete," shares T. "As I grew older, I had to start planning for the long-haul." He shares that his vision of change has evolved since his more radical, confrontational days. "My focus is on taking care of myself and other people in a more immediate way. Smashing things is a young man's game."

Jersey, who has been active at nearly every single pro-Palestinian action in the Bay Area since October, recently took a few days off to decompress, disconnect from social media, and stay at home smoking weed, which usually rejuvenates him and helps him to stim.

The pressure of facing federal charges for his activist work was, understandably, getting to Jersey, as was the frequent online harassment from far-right Christian Zionists. He was in desperate need of a break.

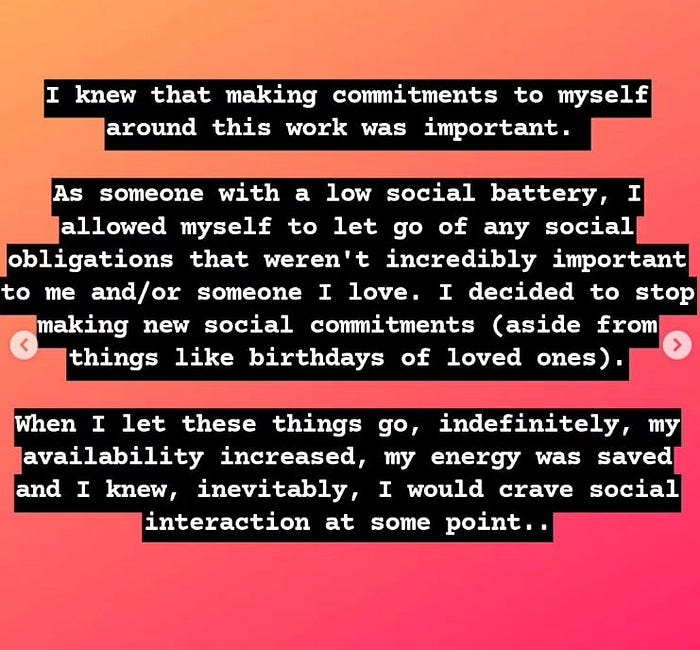

Jersey also shares that since the initial pro-Palestinian protests began, he hasn't made time for much other socializing — and in his case, this has helped to attain a balance between his need for time alone and his need for connection.

"I allowed myself to let go of any social obligations that weren't incredibly important to me or someone I love," he says. "When I let [other social obligations] go…my availability increased…Connecting with people through this cause is actually a lot more fulfilling for me."

This balance might not work for everyone, as certainly many neurodivergent people do need light, unserious socializing in order to be recharged, but I find myself relating a great deal to Jersey. I find honest, vulnerable work that speaks to my real values vastly more rewarding that idle chit-chat.

In the days before October 7th, I truly struggled to fill my weekends at times, recognizing that I needed to take time off and do something "fun" for the sake of my mental health, but finding most public social events to only be draining and fake-feeling. Attending protests has felt like a far more restorative use of my time because it touches both the social part of my brain and my soul.

But still, it comes with its costs. My body gets tired from being in the cold for hours. I have to worry about being censured at my job or fired because of my pro-Palestinian views. Taking in images of mass death is numbing and can be traumatic. And so I must rest, stealing idle hours from my workday and taking long naps in the afternoon and asking my friends to be patient or to consider a protest-date to be a "hangout." I'm quite happy with the balance that I have struck, but it's taken me 35 years of being alive and caring about the world to figure it out.

Even when we are performing noble work that we believe in and find innately rewarding, we will need time to disengage and rest. But that's one of the greatest rewards of building a community: being able to trust that other people will continue to carry the baton of progress for you after you've reached the end of your sprint.

Disabled people are constantly getting told that we aren't trying hard enough to surpass our limits, or that we are faking when we complain of a pain others cannot see. Many of us have come into political activism because we recognize the injustice of being held to a neurotypical, able-bodied standard, but then in our activist work, we often still apply such grueling standards to ourselves. But a world that is nourishing for us to live in is one that will take time. And we can move toward it with gentleness, and plenty of time for rest, and awkward, Autistic honesty, knowing that our defiant, inconvenient differences will help to make that new world more just.

Want to submit a question to Autistic Advice? You can do so here.