🧨 You're Using DateTime.Now — and It's Breaking Your Code

Let's be honest: We've all written this:

if (DateTime.Now > token.Expiry)

{

return Unauthorized();

}It works… until it doesn't.

In production, this little line can wreck your logic due to clock drift, time zone shifts, or mocking nightmares.

The Hidden Dangers of DateTime.Now

While DateTime.Now seems convenient, it's a ticking time bomb for your application, especially in critical scenarios like token validation. Its reliance on the system clock introduces unpredictable external dependencies that can silently, yet catastrophically, break your code.

Here's why DateTime.Now is so problematic:

- Clock Drift: Even well-maintained servers experience subtle discrepancies in their internal clocks. Over time, these minute drifts can accumulate, leading to significant variations between different machines. If a token's expiry is based on a server with a slightly fast clock, and another server with a slightly slow clock attempts to validate it, you could face either premature expiration or, worse, tokens remaining valid long past their intended lifespan.

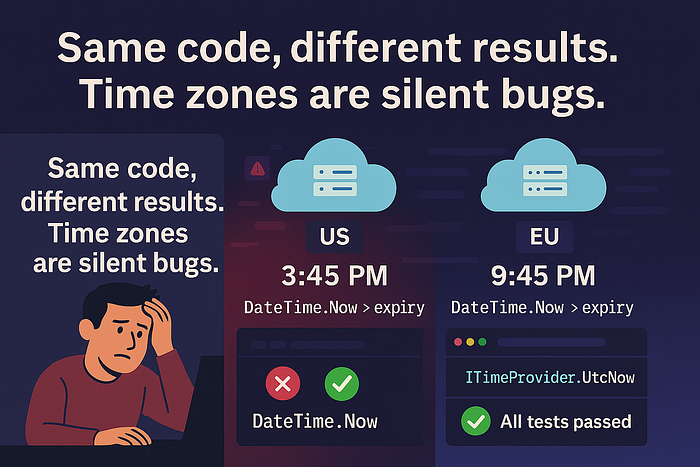

- Time Zone Troubles:

DateTime.Nowreturns the local time of the server it's running on. This is a recipe for disaster in global applications. Imagine a token issued in London (GMT) being validated by a server in New York (EST). Without explicit time zone handling, your application will misinterpret the expiry, leading to authorization failures or security vulnerabilities. - Mocking Nightmares: When it comes to unit testing,

DateTime.Nowis a constant source of frustration. You can't easily control or "mock" the system's current time, making it incredibly difficult to write deterministic and reliable tests for time-sensitive logic. This often leads to brittle tests that fail sporadically or, even worse, critical bugs slipping into production because they weren't adequately tested.

Essentially, DateTime.Now makes your code fragile and susceptible to environmental factors beyond your control. For robust, reliable, and testable applications, especially those dealing with security-sensitive operations like token validation, it's crucial to move away from DateTime.Now and embrace more resilient approaches to time management.

🚨 Why DateTime.Now Is a Trap

DateTime.Now uses the local system clock — and that's dangerous. While it might seem convenient for quick time checks, relying on DateTime.Now for critical application logic is a common pitfall that leads to hard-to-diagnose bugs and unreliable behavior in production.

Here's why DateTime.Now is a trap:

- 🧭 Time zones differ per machine: Your code might work on your development machine but break on a server in a different time zone.

- 🧪 You can't reliably mock it in tests: This makes testing time-sensitive logic incredibly difficult and leads to flaky, non-deterministic tests.

- 🐞 CI/CD servers often run in UTC, devs use local: This common mismatch causes build failures and frustrating debugging.

- 🔐 It causes flaky issues with JWT, cache TTLs, and audit trails: Critical features relying on precise time can fail due to clock drift or time zone discrepancies.

- ☁️ In distributed apps, it causes hard-to-debug inconsistencies: Subtle clock differences across services lead to unpredictable behavior and data issues.

And worst of all: it's invisible until something fails silently. The insidious nature of DateTime.Now is that it often works fine during development and initial testing. The problems only surface in production under specific, often hard-to-replicate, conditions like clock drift, server reboots, or international traffic, making them true "nightmare bugs" to track down.

🧠 DateTime.UtcNow Is Better — But Still Static

Switching to DateTime.UtcNow fixes time zone problems, but it's still a static, hardwired dependency that causes other issues:

- ❌ Still can't override in unit tests: You still can't control the "current time" for testing specific scenarios, leading to unreliable tests.

- ❌ Still breaks when parallel test runners expect different time states: Running tests concurrently can lead to race conditions and unpredictable failures because they all rely on the same, uncontrollable static time.

- ❌ Still unclear in shared libraries: Components using

DateTime.UtcNowhide a critical dependency on the system clock, making them less reusable and harder to reason about.

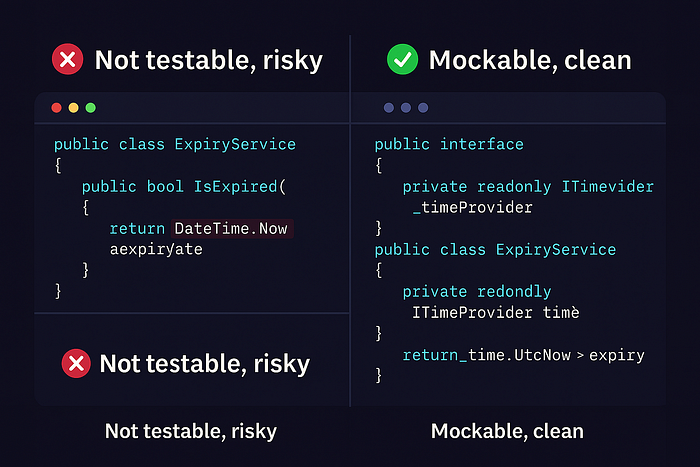

✅ Use ITimeProvider: Abstract Your Clock

Stop calling the system clock directly. Instead, inject a time provider that you control.

public interface ITimeProvider

{

DateTime UtcNow { get; }

}Then use a default implementation:

public class SystemTimeProvider : ITimeProvider

{

public DateTime UtcNow => DateTime.UtcNow;

}Register it with DI:

builder.Services.AddSingleton<ITimeProvider, SystemTimeProvider>();And now you've got testability, flexibility, and safety:

public class TokenService

{

private readonly ITimeProvider _clock;

public TokenService(ITimeProvider clock)

{

_clock = clock;

}

public bool IsExpired(DateTime expiry)

{

return _clock.UtcNow > expiry;

}

}

DateTime.Now vs ✅ ITimeProvider.UtcNow🧪 Want Testable Time? Use a Fake Clock

Create a fake implementation for testing:

public class FakeTimeProvider : ITimeProvider

{

public DateTime UtcNow { get; set; } = DateTime.UtcNow;

}In your test:

var clock = new FakeTimeProvider { UtcNow = new DateTime(2025, 1, 1) };

var service = new TokenService(clock);

Assert.True(service.IsExpired(new DateTime(2024, 12, 31)));🎯 Predictable 🎯 Safe for unit tests 🎯 No fragile hacks or static patches

🔁 Optional Static Clock for Non-DI Usage

For code outside DI (e.g., static methods), add a global wrapper:

public static class Clock

{

public static ITimeProvider Current { get; set; } = new SystemTimeProvider();

public static DateTime Now => Current.UtcNow;

}Then use safely:

if (Clock.Now > expiry) { ... }This hybrid pattern gives you the best of both worlds:

- Testable DI inside app

- Quick static fallback elsewhere

💥 Real-World Bugs You Could Avoid

These are common, silent killers in production:

- ✅ Bug 1: Scheduled task ran early on one machine due to Daylight Saving. A cleanup job executed prematurely, purging data, because

DateTime.Nowdidn't handle the clock shift. - ✅ Bug 2: Redis expiration logic using

Nowinstead ofUtcNowcaused invalidation delays. Different time zones meant cached data persisted too long on some servers, leading to stale content. - ✅ Bug 3: Parallel test runners failed due to inconsistent system clock snapshots. Tests relying on

DateTime.UtcNowexperienced race conditions and unpredictable failures when run concurrently.

These instances show how relying on uncontrolled "now" breaks applications in unpredictable ways.

📌 Developer Checklist

Alright, let's make sure your code never trips over time again. Here's the simple rundown:

- 🚫 Ditch

DateTime.Now: Seriously, just don't use it, especially in the cloud or if you're global. It's a landmine. - ✅ Embrace

UtcNow, but with a twist: Always think UTC, but don't call it directly. Wrap it up! - ➡️ Inject a "Time Teller": Create a little helper (like

ITimeProvider) that tells your code what "now" is. Then, just hand it over using dependency injection. - 🧪 Fake the Clock for Tests: When testing, swap in a "fake" time teller so you control what time it is. No more flaky tests!

- 🏠 Static "Clock" as a last resort: If DI isn't an option (like in old code), a static

Clockclass can be a patchy workaround, but DI is king. - 👀 Stay Sharp on Time Zones & Drift: Even with all this, always keep an eye out for sneaky time zone shifts, Daylight Saving weirdness, and tiny clock drifts. They can still bite!

✅ Why This Post Exists

This isn't just theory; it's a lesson learned the hard way. Back in 2020, my team rolled out a new feature to send scheduled emails precisely at 9 AM. Simple, right?

Not so much.

We had two Azure App Services involved. One was happily running in Central European time, the other strictly in UTC. The result? Our carefully timed emails hit users hours too early. That single screw-up cost us 1,500 unsubscribe clicks. Ouch.

That painful experience solidified one core principle for me: you always wrap your time. Now, I make sure every junior developer I mentor understands this crucial lesson. Directly calling DateTime.Now or DateTime.UtcNow might seem harmless, but as we found out, it's a recipe for real-world, costly failures.

📎 👉 Full Gist Code Sample on GitHub

Includes:

ITimeProviderinterface: A contract for consistent UTC time retrieval.SystemTimeProvider: A production-ready implementation that usesDateTime.UtcNow.FakeTimeProvider: A test-specific implementation allowing explicit time setting for deterministic testing.TokenService(example): Shows how services can depend onITimeProvidervia injection instead of directDateTime.UtcNowcalls.- DI setup: Guides on configuring

SystemTimeProviderfor production use. - Example Test: Demonstrates using

FakeTimeProviderto simulate time in unit tests for reliability.

✅ Stay Connected. Build Better.

🚀 Cut the noise. Write better systems. Build for scale. 🧠 You're reading real-world insights from a senior engineer shipping secure, scalable, cloud-native systems since 2009.

📩 Want more? Subscribe for sharp, actionable takes on modern .NET, microservices, and architecture patterns.

🔗 Let's connect: 💼 LinkedIn — Tech insights, career reflections, and dev debates 🛠R️ GitHub — Production-ready patterns & plugin-based architecture tools 🤝R < style="text-decoration: underline;" rel="noopener ugc nofollow" title="" href="https://www.upwork.com/freelancers/~019243c0d9b337e319?mp_source=share" target="_blank">Upwork — Need a ghost architect? Let's build something real.