This article was updated Sept. 28 at 3:45 p.m. ET.

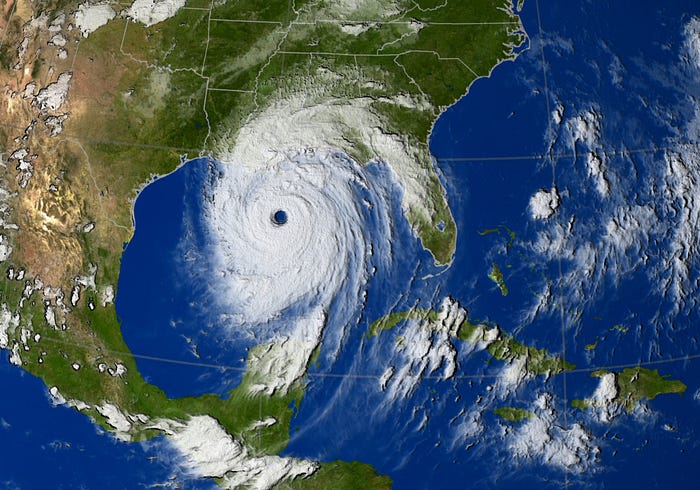

Hurricane Helene's rapid intensification this week and its ultimate power of destruction through record storm surges, high winds and an utter deluge hundreds of miles inland are all reflections of the changing climate, and strong signs of worse superstorms to come.

Helene became a hurricane on Wednesday, Sept. 25. By Thursday night—roughly 36 hours later—it had intensified into an extremely dangerous Category 4 storm with top sustained winds of 140 mph, before slamming into Florida's Big Bend coast. "Helene is the 9th strongest hurricane since 1900 to make landfall in Florida based on minimum sea level pressure," said longtime hurricane forecaster Philip Klotzbach, a research scientist at Colorado State University. And it's "the strongest hurricane to make landfall in the Big Bend of Florida" since modern record-keeping began in 1851, he said.

Helene created record storm surges along the Florida coast, leveling some towns, and generated hurricane-force winds nearly as far north as Atlanta. After picking up tremendous amounts of moisture from the unusually warm Gulf of Mexico, Helene caused landslides amid record flooding in North Carolina and Tennessee, more than 300 miles from where the storm made landfall. More than 40 inches of rain were recorded in two gauges south of Asheville, North Carolina. Flash flooding was reported across many parts of Florida, Georgia and North Carolina and Tennessee, particularly in the Appalachian Mountains. Several dozen deaths have been reported as of this writing.

Helene was the second storm this year to intensify with shocking rapidity and become unusually powerful.

During what's normally a relatively quiet month for hurricanes, on June 28, 2024, tropical storm Beryl formed in the Atlantic with top sustained winds of 35 mph. Within 24 hours it strengthened into a hurricane. A mere 24 hours later, Beryl had intensified into a major Category 4 storm with sustained winds of 150 mph — the first Cat 4 ever in June.

The powerful storm made its way from the Atlantic into the Caribbean, and on July 2 grew into a monster Category 5 hurricane — the earliest Cat 5 ever in the Atlantic basin. Its ultimate top winds of 165 mph set a record for the strongest Atlantic hurricane ever recorded in July. Beryl's winds ultimately subsided to "just" 80 mph before it made landfall in Texas.

Rapid intensification in the modern era

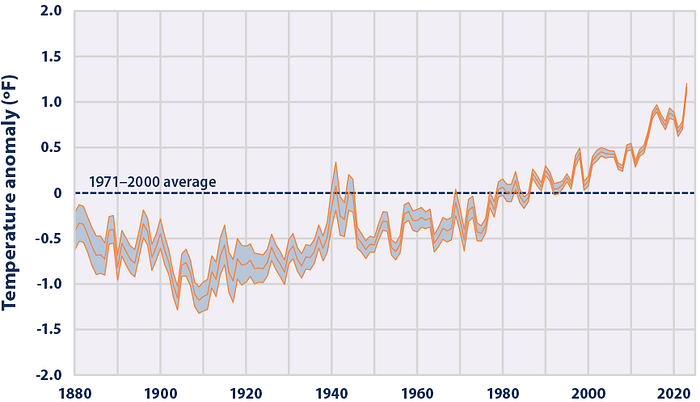

The quick ramp-up to tremendous power of both storms reflect new norms as a warming planet creates bathtub-warm ocean temperatures that fuel stronger storms that whip more quickly into a frenzy and have the potential to become more powerful than they did just a few decades ago.

All this in a hurricane season that's lasting longer than it used to.

Meanwhile, the intensification of hurricane behavior is so stark that experts have begun pondering addition of a 6th category to the Saffir-Simpson intensity scale, as the era of superstorms is expected to bring even more storms that are literally off the charts.

A study last year analyzed how rapidly hurricanes intensify, comparing the period 1970 through 1990 to what they termed the modern era of 2001 through 2020.

Atlantic hurricanes in the modern era are more than twice as likely to strengthen from Category 1 to Category 3 in a 24-hour period than in the previous era, the analysis suggested.

"In the modern era, it is about as likely for hurricanes to intensify by at least 57 mph in 24 hours, and more likely for hurricanes to intensify by at least 23 mph within 24 hours, than it was for storms to intensify by these amounts in 36 hours in the historical era," said study leader Andra Garner, an assistant professor of environmental sciences at Rowan University.

"The number of times that hurricanes strengthen from a Category 1 storm (or weaker) into a major hurricane (Category 3 or greater) within 36 hours has also more than doubled in the modern era relative to the historical era," Garner said.

Off the charts

The classification system for hurricanes tops out at Category 5, an open-ended designation for the most ferocious storms packing sustained winds of 157 mph or more. But the scale has become insufficient to handle increasingly powerful storms that have developed as the planet grows warmer, including a handful that exceeded 192 mph — colossal tempests some scientists say should be designated as Category 6.

Comprehensive research has found that the maximum sustained winds of the strongest hurricanes are getting stronger in nearly every region where they form and develop.

Since 1980, five tropical systems would have been designated as Category 6 storms, if such a category formally existed, scientists concluded in a study published earlier this year.

All five storms occurred in the past nine years. Each was in the Pacific Ocean, but the Atlantic has also produced hurricanes testing the limits of the Cat 5 classification, the scientists explained in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Eight Atlantic hurricanes since 1980 have produced sustained winds of 180 mph or greater, they found.

The researchers have not formally proposed revising the hurricane scale, but rather presented their findings to illuminate the shortcomings in communicating potential public threats using the current scale.

"Our motivation is to reconsider how the open-endedness of the Saffir-Simpson Scale can lead to underestimation of risk, and, in particular, how this underestimation becomes increasingly problematic in a warming world," said study team member Michael Wehner, a climate scientist at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

What's driving more powerful storms

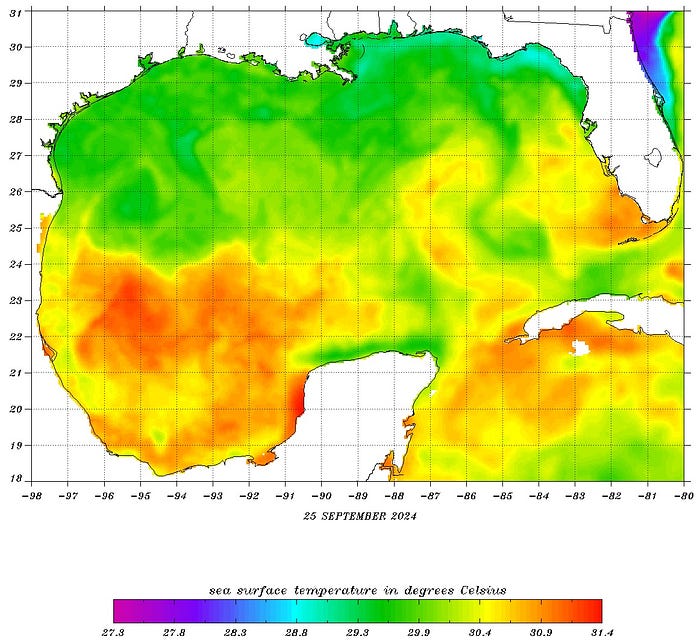

The main fuel for any hurricane is warm water. Hurricanes typically need sea surface temperatures of around 80 degrees Fahrenheit (26.7 C) to develop and stay intact. Warm seas also cause lower atmospheric pressure and increased instability in the atmosphere — additional factors that promote storm formation.

Warmer ocean temperatures, part of an overall warming planet, are expected to fuel stronger hurricanes, increasing the overall odds of powerful storms striking the US, multiple research groups have concluded.

"Generally speaking, the warmer the water temperatures, the more heat energy is available and the higher the potential for tropical cyclones to develop," Florida meteorologist Jeff Berardelli has explained. "So it's reasonable to assume that as humans continue to release planet-warming greenhouse gases, the likelihood of tropical cyclone activity increases."

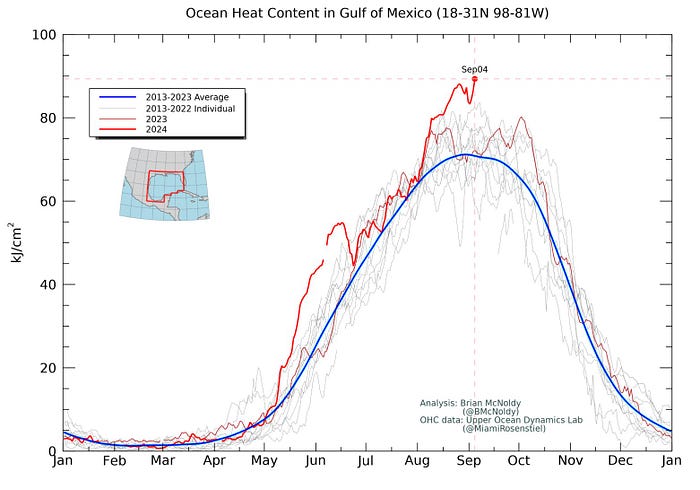

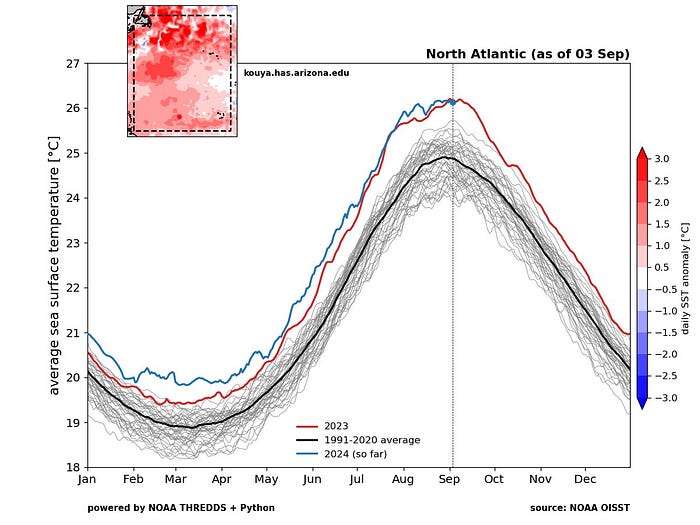

High water temperatures in the Gulf of Mexico are surprising even the scientists who regularly monitor this stuff.

"The ocean heat content averaged over the Gulf of Mexico is obliterating previous all-time record highs," Brian McNoldy, a hurricane researcher at the University of Miami, said on Sept. 4. "It's 126% of average for the date." He called the measurement "pretty amazing."

Heat content in the broader Atlantic ocean was also "extremely anomalously warm for the date," McNoldy said.

Hurricane season is getting longer

Warmer seas take longer to cool down as season's change. No surprise, then, that hurricane season—defined as running from June 1 to Nov. 30—has also begun defying definition.

In 2016, hurricane Alex formed in the Atlantic ocean in January—the first storm on record to do so since 1938. That's a clear anomoly.

But tropical storms—the predecessors of hurricanes—have frequently formed before the season officially begins. Since 2015, seven tropical storms have formed in May in the Atlantic, and one in April (Arlene, 2017). In 2005, meteorologists ran out of regular alphabetized names during an incredibly busy season. The 27th named tropical storm that year—Epsilon—formed in November and became, quite unexpectedly, a hurricane in early December.

"Climate change is causing warmer sea surface temperatures for a longer period of time," said Louisiana State Climatologist Barry Keim. "Warmer atmosphere and sea surface temperatures would result in a longer season because you're over the 80-degree threshold to support a storm, so it makes logical sense that hurricane season would expand in both directions."

Rainfall totals rising

Not only are hurricanes today stronger, on average, but they are dumping more rain when they come ashore.

Hurricane Maria, in 2017, dropped an unprecedented 41 inches (1.04 meters) of rain on parts of Puerto Rico. Global warming played a role in that epic rain event, according to a study of the conditions.

"What we found was that Maria's magnitude of peak precipitation is much more likely in the climate of 2017 when it happened versus the beginning of the record in 1950," said the study's lead author, David Keellings, a geographer at the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa.

Likewise, Hurricane Harvey, also in 2017, soaked parts of the Gulf Coast with up to 50 inches (1.27 meters) of rain.

"Record high ocean heat values not only increased the fuel available to sustain and intensify Harvey but also increased its flooding rains on land," researchers concluded in a subsequent analysis. "Harvey could not have produced so much rain without human-induced climate change."

Climate change is driving more extreme rainfall events outside hurricanes, too. One year ago this week, 8.65 inches of rain fell at New York's John F. Kennedy Airport—more than on any September day ever recorded. Research has suggested further warming will bring 100-year floods every 10 to 15 years, and possibly even annually.

Expect more superstorms

The already observed trends of stronger storms and heavier rainfall totals allow scientists to predict future patterns based on expectations of continued climate change.

The era of superstorms has just begun, the experts warn. In fact, they've been warning about this for a decade or more.

A post-mortem on Superstorm Sandy, which devastated parts of New Jersey and New York back in 2012, used computer models to predict how a future Sandy might behave with warmer ocean temperatures. The results are almost too scary to imagine: winds up to 80% more destructive and up to 50% heavier rainfall.

Another exacerbating factor often not considered in the destructive ability of hurricanes: As ocean temperatures increase, the sea level rises, both because of melted glaciers and the expansion of water when it warms. Higher sea levels were responsible an additional 71,000 people being affected by Sandy's flooding.

Computer models are imperfect, of course. But there is zero doubt that if the atmosphere and seas continue to warm, as is expected, then hurricanes will get stronger and dump even more rain than they would have under climate conditions of the present or the past. Multiple analyses by different research groups have indicated this scenario. One study, using computer simulations of climate change, predicts that by the end of this century, the average rainfall rate in hurricanes will increase 24%.

Separate simulations done by Wehner and his colleagues suggest that if the climate warms to 2 degrees Celsius (3.6° Fahrenheit) above pre-industrial levels, the risk of hypothetical Category 6 storms doubles in the Gulf of Mexico.

"Even under the relatively low global warming targets of the Paris Agreement, which seeks to limit global warming to just 1.5°C above pre-industrial temperatures by the end of this century, the increased chances of Category 6 storms are substantial in these simulations," Wehner said.

I've been reporting on hurricanes since the early 1990s while a journalist at the Asbury Park Press and later The Star-Ledger in New Jersey. If hurricanes interest you, check out my science-based novel 5 Days to Landfall. — Rob