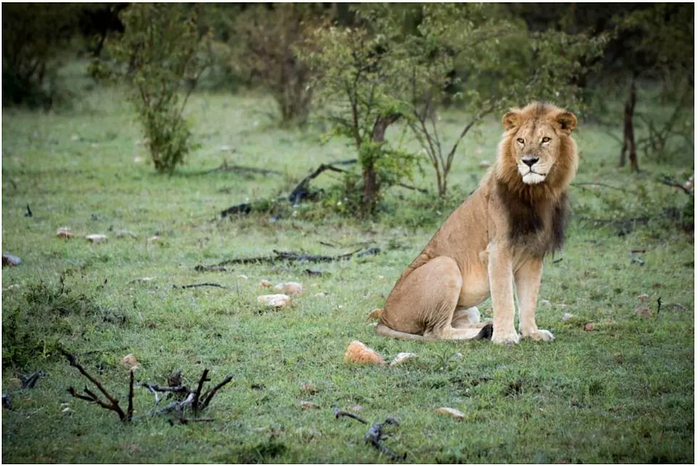

A study recently came out that documents how a tiny invasive ant is affecting the mighty lion on the savannahs of Kenya, demonstrating the ecological connections between all life regardless of how great or small

© by GrrlScientist for Forbes | LinkTr.ee

In a remarkable, but accidental, real-life experiment demonstrating the ecological connections between all life regardless of how great or small, a study recently came out that documents how a tiny ant is affecting the mighty lion on the savannahs of Kenya.

This ant is invasive and it's far from home. It probably arrived from the island of Mauritius, located in the Indian Ocean, early during the last century, and began establishing itself in the Ol Pejeta Conservancy in Kenya around 20 years ago.

"It showed up in people's houses and other centers of human activity," said the study's senior author, animal ecologist Jacob Goheen, a Professor of Zoology & Physiology and of Botany at the University of Wyoming. Professor Goheen's expertise is linking theory with data as he works to better understand community dynamics and structure, animal-plant interactions, and conservation biology.

"To the best of our knowledge, it was introduced in bushels of produce from somewhere in the Indian Ocean," Professor Goheen stated.

The ants, known as big-headed ants, Pheidole megacephala, build and live in huge underground metropolises, like most of the ant species that you're familiar with. After they invaded, these small ants hunted down and killed the native acacia ants, and ate their pupae, and eggs.

The native acacia ants live symbiotically with whistling thorn acacia trees, Vachellia drepanolobium. In exchange for food and shelter provided by the trees' bulbous thorns, acacia ants act as bodyguards, vigorously protecting their landlord-trees from predation by hungry giraffes, elephants and other large herbivores.

"Much to our surprise, we found that these little ants serve as incredibly strong defenders and were essentially stabilizing the tree cover in these landscapes, making it possible for the acacia trees to persist in a place with so many big plant-eating mammals," said the study's second co-author, ecologist and conservation biologist Todd Palmer, a biology professor at the University of Florida.

Acacia ants' bites are quite painful because they contain formic acid, which is the caustic burning chemical that makes many insect stings (and stinging nettle attacks) very painful. The native acacia ants are especially well-equipped for attacking hungry elephants by swarming up their noses, biting madly all along the way. This mutually beneficial ecological relationship between acacia trees and acacia ants is known by biologists as a mutualism.

Unfortunately, invasive big-headed ants offer no such protection to acacia trees, and because they kill the physically larger acacia ants, the trees are suddenly rendered vulnerable to elephant attacks. As a result, elephants began crushing and eating the acacia trees, destroying the tree cover. Thus, after invasion by big-headed ants, the landscape was transformed into a much more open habitat, largely devoid of brush, small trees and woodland.

Predictably, Professor Palmer, Professor Goheen and collaborators found that elephant attacks resulted in five to seven times more broken trees than when native acacia ants are present.

Lions are ambush predators that live on the savannah. As the tree cover was lost to marauding megaherbivores, Professor Palmer, Professor Goheen and collaborators wondered how this transformation might affect the relationship between lions and zebras, their favorite prey? Would zebras be more likely to spy stalking lions and flee?

To test this hypothesis, the researchers set up study areas where big-headed ants have invaded and compared them to areas without big-headed ants, and measured the interactions between lions and zebras. They found, as they had predicted, that the big-headed ant invasion did indeed reduce zebra kills because the zebras could spot hunting lions from a long way away and take evasive action.

"We show that the spread of the big-headed ant, one of the globe's most widespread and ecologically impactful invaders, has sparked an ecological chain reaction that reduces the success by which lions can hunt their primary prey," Professor Palmer, Professor Goheen and collaborators wrote in their elegant and insightful study (ref).

Further, Professor Palmer, Professor Goheen and collaborators documented that between 2003 to 2020, the number of zebras killed by lions declined from 67% to 42%, whilst the number of buffalo killed by lions surged from 0% to 42%. The team also found that lions were almost 3 times more likely to attack and kill zebras in wooded, tree-covered parts of the park — which is what most of the park once was — rather than on the open grasslands that recently appeared, demonstrating the dramatic impact of just one tiny invasive insect on an entire food web.

What was most surprising?

"I was most surprised by how readily lions switched from killing zebra — their primary prey — to more formidable buffalo," Professor Goheen replied.

"These tiny invaders are cryptically pulling on the ties that bind an African ecosystem together, determining who is eaten and where," Professor Palmer observed.

The team used hidden camera traps, they satellite-tracked collared lions and they applied statistical modeling methods to analyze more than three decades of data, and to detail the complex interactions between ants, trees, lions, zebras, buffalo and elephants. But the main source of inspiration and data for this body of research came from decades of fieldwork.

"There are a lot of new tools involving big data approaches and artificial intelligence that are available today," Professor Palmer explained, "but this study was born of driving around in Land Rovers in the mud for 30 years."

What might be the longer-term effects of these ants' invasion?

"We don't know what's going to happen going forward," replied the study's lead author, Kenyan conservation ecologist Douglas Kamaru, a doctoral candidate at the University of Wyoming who studies the links between breakdowns of ecological mutualisms, changes in landscapes, and predator-prey dynamics in a human-occupied savannah.

"It's very difficult for lions to kill buffalo," Mr Kamaru pointed out. "It's a lot of energy compared to [hunting] zebra, and sometimes buffaloes kill lions when they're fighting."

Because the risk of death or serious injury from attacking a buffalo is greater than from attacking a zebra, it takes a larger group of lions to hunt and successfully kill buffalo, which raises the question: will the lions living on the Ol Pejeta Conservancy form larger prides to accommodate their switch to a larger and more dangerous prey species?

"Nature is clever, and critters like lions tend to find solutions to the problems they face," Professor Palmer replied, "but we don't yet know what could result from this profound switch in the lions' hunting strategy. We are keenly interested in following up on this story."

Although the effect of invasive ants has caused problems for buffalo, the number of lions present remains unchanged. But other animals in the area are impacted too, especially Endangered black rhinos, Diceros bicornis, which primarily dine on acacia trees, according to Professor Goheen.

"One of the surprises about this [study] was that these ecological chain reactions, that are triggered by an invasive species, affect a bunch of other species that have seemingly very little to do with that ant-tree mutualism," Professor Goheen pointed out.

This elegant and deeply worrying study identifies how a particular disturbance echoes throughout a complex web of ecological interactions within a specific ecosystem, by providing careful documentation for the famous "butterfly effect".

"Oftentimes, we find it's the little things that rule the world," Professor Palmer explained. "These tiny invasive ants showed up maybe 15 years ago, and none of us noticed because they aren't aggressive toward big critters, including people. We now see they are transforming landscapes in very subtle ways but with devastating effects."

Professor Palmer, Professor Goheen, Mr Kamaru and collaborators are now working to develop solutions to stop the loss of tree cover in these iconic landscapes.

"We are working with land managers to investigate interventions, including temporarily fencing out large herbivores, to minimize the impact of ant invaders on tree populations," Professor Palmer said.

"The role of behavioral adjustments in underlying the population stability of lions, plus the degree to which such stability can be maintained as big-headed ants advance across the landscape, remain open questions for future investigation."

At this point, it's not clear that big-headed ants can be stopped: they currently are marching across the savannah at a rate of 160 feet per year. Worse, these invasive ants can be found almost everywhere on the planet.

"These ants are everywhere, especially in the tropics and subtropics," Professor Palmer remarked. "You can find them in your backyard in Florida, and it's people who are moving them around."

Professor Palmer, Professor Goheen, Mr Kamaru and collaborators say they'll continue watching and measuring the changes in the area to see whether efforts to control the ant invasion work, whether the lions continue adapting their diets successfully and how other animals on the reserve are affected by this cascade of ecological changes. But there's yet another wild card: the warming and drying climate, which could cause huge shifts to the ecosystem.

Sources:

Douglas N. Kamaru, Todd M. Palmer, Corinna Riginos, Adam T. Ford, Jayne Belnap, Robert M. Chira, John M. Githaiga, Benard C. Gituku, Brandon R. Hays, Cyrus M. Kavwele, Alfred K. Kibungei, Clayton T. Lamb, Nelly J. Maiyo, Patrick D. Milligan, Samuel Mutisya, Caroline C. Ng'weno, Michael Ogutu, Alejandro G. Pietrek, Brendon T. Wildt and Jacob R. Goheen (2024) Disruption of an ant-plant mutualism shapes interactions between lions and their primary prey, Science 383(6681):433–438 | doi:10.1126/science.adg1464

Socials: Bluesky | CounterSocial | LinkedIn | Mastodon | MeWe | Post.News | Spoutible | SubStack | Tribel | Tumblr | Twitter

Originally published at Forbes.com on 5 February 2024.