Curated and Distributed in Philosophy | Self

Coping With an Overabundance of Mankind's Greatest Mental Resource

Knowledge is everywhere. It is the fundamental resource of the human mind and in the midst of the digital age, we find access to it in every nook and cranny that we dare to look.

The ever-evolving list of the best-selling books. Instant access to thought-pieces and researched-based articles scattered all over the internet. The flood of intriguing educational visual and virtual content.

For the curious and knowledge-hungry mind, this reality duals as both a wet-dream and a nightmare in that they have to deal with having too much to choose and learn from — the paradox of choice.

This leads to expected behaviors that you, my curious friend, might identify with:

- Buying more books than you have time to read especially when you have a collection of unread books in your personal library still waiting to be read

- Saving yet another article to read later on Medium to go along with your collection of the other 100 articles that intrigued you in the past

- Adding another lecture or video essay to your watch-later playlist on Youtube

In Japan, the term best used to describe this is Tsundoku, which translates to the acquisition of reading material but letting them pile up in one's home without reading them — in our modern world I believe this term can capture the same meaning with saved online articles and videos (for brevity, books will be used interchangeably with digital content).

This can understandably be a cause of guilt. The pressing feeling you get when you go out to acquire a new piece of material knowing full well that you haven't digested everything you've collected in the past.

Next thing you know, you have piles and piles of books and long lists of saved content that are just waiting to be consumed but never will because you acclimated a collection so large that it'd take several lifetimes to reasonably get through all of it.

Maybe this makes you anxious, but what if I told you that this is a very good habit to have? That oversaturating your library with untouched and unconsumed material might provide far more value and purpose to your life than any piece of consumed content ever will?

It's a bold claim, but that's exactly what Nassim Nicolas Taleb claims in his critically-acclaimed book, The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable:

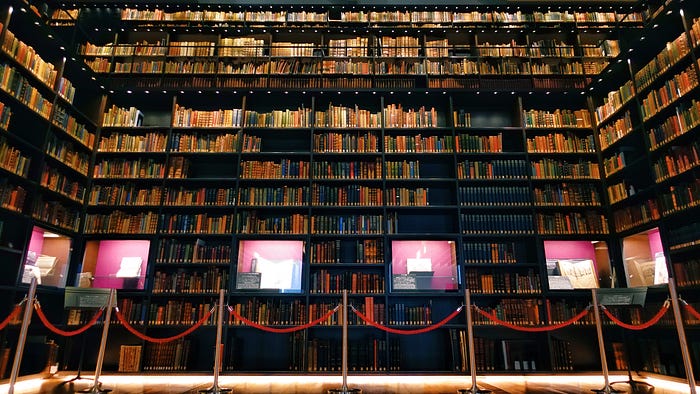

"Read books are far less valuable than unread ones. The library should contain as much of what you do not know as your financial means, mortgage rates, and the currently tight real-estate market allow you to put there."

The Antilibrary — A Boundless Fountain of Curiosity

Understanding that read books are far less valuable than unread ones might appear very counter-intuitive and confusing to you.

That's okay. Knowledge itself seems to have been put on a pedestal these days where people tend to form their identity around the number of books that they've read, their educational institution, and everything that they do know.

The problem with this is perfectly illuminated by Lincoln Steffens' quote from his 1925 essay, Radiant Fatherhood:

"It is our knowledge — the things we are sure of — that makes the world go wrong and keeps us from seeing and learning."

Certainty in a world clouded in mystery has become mainstream. Marcello Gleiser highlights in his book, The Island of Knowledge, that we have a tendency to constantly strive towards more and more knowledge, but that it is essential to understand that we are, and will remain, surrounded by mystery. Science after all is driven by the unknown answers to calibrated questions of nature.

That's why the antilibrary is such an important tool— the intentional act of pursuing Tsundoku for monetary personal growth.

Coined by Nassim Taleb in his book, The Black Swan, he describes the antilibrary and its role in battling ignorant certainty by using legendary writer Umberto Eco's relationship with books as a means to show what a fruitful relationship with knowledge really looks like.

Umberto Eco had a very large personal library amounting to thousands of books, so whenever he had visitors, he'd often separate them into two categories. There were those who were fascinated by his library and would ask how much he has read, whereas the other very small minority would actually understand that a library was not meant to be an ego-booster, but rather a very powerful research tool. The library, to him, was not a mere ornament of knowledge, but rather a means to constantly remind himself that there exists a sea of knowledge out there that has yet to be explored — that he will never be able to explore.

Therefore it's clear that the antilibrary serves the purpose of being an intellectual reminder about how much there is to explore in the world, to stay curious, and that you don't know as much as you think you know — there's always more to learn and knowledge will never be complete.

It allows you to be comfortably conscious of your ignorance, thus sparking a fire in your belly to keep on learning. As Stuart Feinstein points out in his Ted Talk and book, Ignorance: How it Drives Science, being consciously ignorant is to have faith in uncertainty, finding pleasure in mystery, and learning to cultivate doubt as there is no surer way to screw up an experiment than to be certain of its outcome.

Though I may find a little discomfort in knowing that I won't finish all of the books that I have in my library, I have cultivated this constant drive to learn more and more in due part to that discomfort. Every time I look, I get reminded of the pressing reality that I will never know all that I want to know, but I can at least try and bring light to the shadows of my ignorant mind.

High Supply + High Demand = Increased Sense of Urgency to Get More Done

Psychology Today published an article on the importance of managing time and had this to say:

Time management is really "personal management" and it is a skill necessary for achieving a better quality of life. By managing your time in a more efficient way, not only you will get the right things done, but you'll also have enough time to relax, de-stress, and breathe more freely.

Andrew Kirby, a self-help YouTuber and founder of Time-Theory (a company aimed to eliminate procrastination and increase productivity among its clients), suggests that by increasing your demand for time and putting more things on your plate — without putting so much that you'll overwhelm yourself — you'll get more done.

He found this to be true among his clients where he discovered the relationship between the increased demand for time and the increased sense of urgency.

When talking about Tsundoku in one of his videos, he discusses how a large library of unread books serves as a way to fundamentally instill that demand of time and urgency into your mind simply through the increase of supply.

This isn't surprising when we think about what was mentioned before. When you have a library of unread books, you increase your inner sense of curiosity and drive to learn more. When you have so many books in front of you that you want to consume and know that every single one requires a large commitment of time, you'll learn to more wisely choose what you decide to spend time on since you might come to the realization that the time you have to consume such content is finite. Knowing that time is finite is exactly what catalyzes a sense of urgency.

As this article from Entrepreneur Magazine states,

"Creating a sense of urgency is rarely talked about when discussing all of the required characteristics that make up the highly successful, but without a doubt, it's a prerequisite for success in business and in the pursuit of achieving your personal goals and dreams."

Therefore, that urgency that you do receive not only teaches you to get more reading and learning done, but it also might provide a path for that urgency to trickle down into other disciplines in your life thus potentially alleviating you of any crippling feelings of procrastination that you may be suffering.

Embrace the Subtle Power of Tsundoku to Transform Your Life

Don't be embarrassed or feel any sort of guilt by diving too quickly into another domain of knowledge before you even explore all the previous domains you were curious about in the past.

Life is nothing more than a constant journey of exploration and discovery.

Our minds change, our interests shift, and our curiosities flower in response to the exposure of previously learned knowledge.

Therefore, the constant acquisition of more books and content based on your current curiosities should instead serve as a reminder to yourself about how curious you are — that alone should make you feel proud of your own mind and the personal pursuit of worldly understanding.

Tsundoku should not, therefore, be seen as a vice, but rather as a virtue that illuminates the beautiful shades of the mind and propels you closer to a potentially more fulfilling, productive, and urgent existence.