In 1955, an outbreak of encephalomyelitis struck the Royal Free Hospital Group in London, U.K., hospitalizing over 200 patients. Encephalomyelitis is the inflammation of the brain and spinal cord, typically caused by infections. But what's intriguing is that about 2% of the patients developed what is known today as myalgic encephalomyelitis or chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), which is also a subtype of long-Covid.

This incident was published in the British Medical Journal in 1957, which is likely the earliest record of ME/CFS. But the subsequent decades were met with widespread skepticism about this condition. A few experts even believed ME/CFS is psychosocial, a hysteria of some sort. As a result, the amount of research done on ME/CFS was pitiful. Getting funding to do research on ME/CFS was notoriously hard as well.

Today, we're paying the price. The pathomechanisms (patho- means disease) of ME/CFS — as well as its risk factors, prognosis, and treatments — remain poorly understood. We have bits of studies covering different pathomechanisms of ME/CFS but none were unifying and convincing.

But this is about to change, thanks to recent, comprehensive research from the U.S. National Institute of Health (NIH).

A deep dive

The NIH study, titled "Deep phenotyping of post-infectious myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome," was published in Nature Communications in February 2024. This paper has over 70 authors, reflecting the amount of research done in this single paper.

What this study did right from the start was to recruit the right people. Due to the absence of a diagnostic biomarker and over 20 diagnostic criteria, existing ME/CFS research has suffered recruitment inconsistency. To this end, the NIH study established strict inclusion criteria that included comprehensive medical and psychological assessments to reduce the likelihood of incorrect diagnosis.

As a result, the study ended up with 17 ME/CFS patients out of the initial 217 cases inquired during its recruitment process from 2016 to 2020. During this screening process, as many as one-fifth of the initial ME/CFS cases were found to be due to other medical conditions after all.

This group of 17 ME/CFS patients is quite similar in terms of manifestation, duration, and trigger (some sort of infection) of symptoms. These patients were paired with 21 healthy controls with similar age, sex, and BMI.

Initially, I also suspected what such a small sample size could tell us. But I realized that the consistency and precision of the group are more important than the size — quality over quantity — especially when sophisticated pathomechanisms are at play. We want to know we're truly examining a group that represents the condition.

These participants underwent all sorts of medical examinations to map what was going on in the body as much as possible. The paper is 24 pages long, excluding the reference list, and the methods section alone is nearly 10 pages long. No, their font size and spacing aren't big.

Without further delay, their results found that ME/CFS comes with:

1. Cardiovascular autonomic dysfunction

Compared to healthy controls, ME/CFS patients exhibited decreased heart rate variability (HRV) — with increased daytime heart rate (indicating ↑ sympathetic activity) and diminished drop in nighttime heart rate (indicating ↓ parasympathetic activity) — as well as longer blood pressure recovery times (indicating ↓ baroreflex-cardiovagal function).

The autonomic nervous system controls involuntary functions, such as heart rate. HRV refers to the variation in the time intervals between heartbeats, which is a measure of the heart's ability to respond to different physiological conditions and stresses. HRV is an indicator of the autonomic nervous system's balance and efficiency; higher variability generally suggests better cardiovascular fitness and stress resilience, while lower variability can indicate stress, fatigue, or underlying health issues.

The baroreflex-cardiovagal function refers to the vagus nerve's ability to regulate heart rate in response to changes in blood pressure. When blood pressure rises, the baroreflex stimulates the vagus nerve to slow down the heart rate to stabilize blood pressure. Conversely, when blood pressure drops, this reflex reduces vagal tone, allowing the heart rate to increase.

Altogether, the presence of lower HRV and reduced baroreflex-cardiovagal function indicates that the autonomic nervous system control of the cardiovascular system is compromised in ME/CFS patients.

2. Impaired brain-muscle connection

Both healthy controls and ME/CFS patients showed similar maximum grip strength. But the problem is that ME/CFS patients could not maintain their maximum grip strength for as long or as many repetitions as the healthy controls. This suggests that the fatigue in ME/CFS isn't due to muscle weakness but some neuromuscular control.

Subsequent brain stimulation tests revealed that the motor cortex in the brain became less active after exercise—returning to baseline—in healthy controls. But the motor cortex remains active in ME/CFS patients, indicating that their brains remained overly active and possibly less efficient in controlling muscle movements.

Further brain imaging tests found that ME/CFS patients had decreased brain activities in areas related to integrating sensory information and executing a motor response. These brain areas were the temporoparietal junction, superior parietal lobe, and right temporal gyrus, which also influences the activity of the motor cortex.

These differences in brain activities suggest that ME/CFS patients have a reduced ability to sustain brain-muscle engagement during prolonged or repeated tasks.

3. Reduced cardiopulmonary performance

During cardiopulmonary exercise testing, both healthy controls and ME/CFS patients do reach similar peak respiratory exchange ratios (indicating maximal effort), but the latter have lower peak power, respiratory and heart rates, and oxygen uptake.

This implies that even though ME/CFS patients can exert maximal effort, their physical or mechanical output (peak power) does not match up, highlighting a disparity between effort and actual performance.

Furthermore, ME/CFS patients displayed a slower increase in heart rate during exercise. They also reached their anaerobic threshold — a point during intense exercise when the body shifts from oxygen-based energy production to less efficient, anaerobic metabolism— at lower oxygen consumption levels, suggesting an earlier onset of fatigue.

When the body shifts to anaerobic energy production, it indicates that it can no longer meet its energy demands through oxygen-based (aerobic) processes alone. This shift occurring at lower exercise intensities suggests that ME/CFS patients have compromised cardiopulmonary fitness.

4. Altered neurotransmitter activities

In the cerebrospinal fluid of ME/CFS patients, levels of DOPA, DOPAC, and DHPG were decreased compared to healthy controls. DOPA (dihydroxyphenylalanine) is a precursor to dopamine synthesis. DOPAC (dihydroxyphenylacetic acid) and DHPG (dihydroxyphenylglycol) are by-products of dopamine and norepinephrine when metabolized.

But levels of the neurotransmitters dopamine and norepinephrine did not differ between the groups. Dopamine and norepinephrine belong to a class of neurotransmitters called catecholamines or catechols. Thus, altered levels of their precursors or metabolites suggest problems in how these catechol neurotransmitters are processed or regulated. In the study, altered catechols also correlated with physical and cognitive fatigue.

Further analyses revealed that metabolites related to the tryptophan and serotonin neurotransmitter pathway were significantly altered in ME/CFS, especially in females, compared to healthy controls. In contrast, specific decreases in threonine and glutamine were noted in males.

The cerebrospinal fluid profile better reflects what's going on in the brain than standard blood tests. Altered neurotransmitter activities therein would indicate some sort of neurological dysfunction in the brain, consistent with the previous findings on impaired autonomic-cardiovascular and brain-muscle connection.

5. Altered muscular gene activities

Similar to the altered immune profile, ME/CFS also comes with altered muscle-related gene activities that are sex-dependent.

In males, genes involved in sugar metabolism and mitochondrial functions were downregulated, while genes related to the breakdown of fatty acids were upregulated — indicating changes in how muscle cells process energy.

For females, genes linked to growth hormone receptor signaling and protein regulation by ubiquitin were upregulated, while those involved in fatty acid oxidation and mitochondrial functions were downregulated. This pattern suggests a disruption in energy processes within the muscles.

Therefore, these findings indicate significant differences in muscle gene expression between men and women with ME/CFS, reflecting distinct changes in muscle energy metabolism that are consistent with the previous finding on impaired brain-muscle connection.

6. Altered immunological activities

Compared to healthy controls, ME/CFS patients had elevated levels of PD-1 (programmed death-1), a marker of T-cell exhaustion, in their cerebrospinal fluid. ME/CFS patients also showed a shift in B-cell types in the blood, with increased naïve B-cells but decreased memory B-cells.

When analyzed by sex, male patients had increased expression of certain receptors on T-cells in cerebrospinal fluid, while female patients had more naïve T-cells in their blood. Moreover, gene expression analyses found that men had changes in genes linked to immune signaling, while women had alterations in genes linked to B-cell functions.

Overall, these findings highlight that immune changes related to T-cells and B-cells in ME/CFS are complex and differ between sexes.

7. Altered gut microbiota profile

Microbial analyses of stool samples revealed that patients with ME/CFS exhibited lower diversity in their gut microbiota compared to healthy controls. The overall composition of the gut microbiota — as in the type and amount of bacteria present — also varies between the two groups.

8. Others

There were no differences in lung ventilatory function, muscle oxygenation, resting energy expenditure, basal mitochondrial function of immune cells, muscle fiber composition, or body composition. These null findings indicate there's no resting low-energy state in ME/CFS.

Other null results include the absence of lymph node enlargement, brain lesions, brain inflammation, small fiber neuropathy, neuronal injury, heavy metal toxicity, hypermobility, mitochondrial function, orthostatic hypotension, cell senescence, and autoimmunity.

These null findings indicate that these factors are not involved in the pathomechanisms of ME/CFS and, thus, may not be effective targets for clinical treatments of this condition.

Putting it altogether

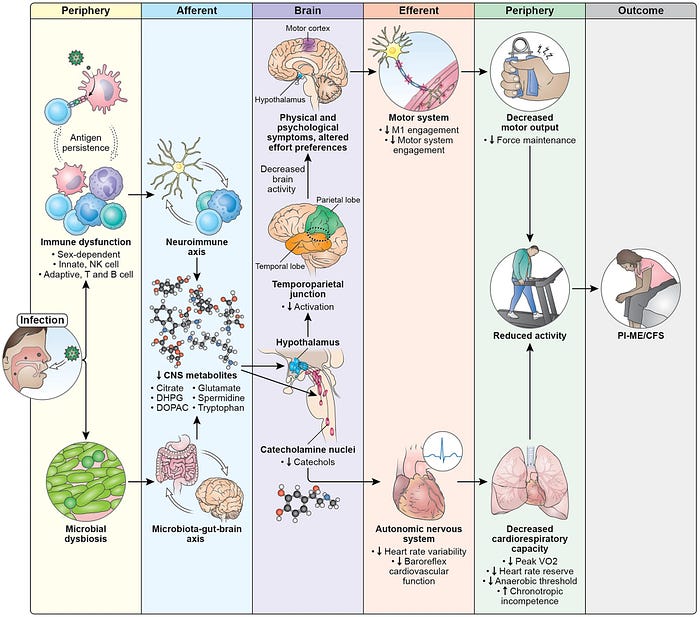

Based on the findings, the study authors mapped out a model proposal of the disease mechanisms (pathomechanisms) of ME/CFS (Figure 1).

First, an infection triggers immune dysfunction and gut dysbiosis (i.e., a negative alteration in gut microbiota), which may remain unresolved and persist long-term. These immune and gut microbial shifts may affect the brain, resulting in reduced levels of various metabolites related to the metabolism of catecholamines and other neurotransmitters.

The altered biochemical environment would then affect several brain structures, including the autonomic nervous system center in the brain. Such autonomic dysfunction may consequently decrease both heart rate variability (HRV) and baroreflex-cardiovagal function, with downstream impairments in cardiopulmonary capacity.

Brain structures involved in muscular control, notably the motor cortex, would also be impaired. This leads to reduced physical capacity, especially in maintaining force output. And this is further exacerbated by the impaired autonomic-cardiovascular and cardiopulmonary systems.

Importantly, according to the study authors, this model identifies promising areas for therapeutic intervention and explains why some treatments might fail. For instance, the presence of T-cell exhaustion suggests that immune checkpoint inhibitors could help by removing persistent foreign antigens. Neurochemical changes affecting neuronal circuits may offer another intervention point.

However, targeting symptoms alone — such as with exercise, cognitive behavioral therapy, or therapies aimed at the autonomic system — may not address the underlying pathomechanisms of ME/CFS.

"This is a more extensive set of biological measurements in people with post-infectious ME/CFS than any previous study," said Avindra Nath, MD, clinical director at the NIH who directed the study. "It reveals that there is an absolute biological basis for this disease, involving clear immune system [and neurological] abnormalities."

The way forward

According to NeurologyToday, other experts in the field describe the NIH study as highly important, mainly because it's the most extensive study to date that validates a biological basis for ME/CFS.

"In the history of neurology, we've had a lot of diseases that were difficult to explain and would often be characterized as 'malingering' or 'hysteria,' such as epilepsy and dystonia," Dr. Nath explained. "As our science has gotten more sophisticated, we have begun to understand that these are true brain-driven diseases that can be treated, and no one dismisses them anymore. ME/CFS has faced that same skepticism."

As mentioned in the introduction of this article, ME/CFS has faced widespread dismissal for decades since its first description in 1955. Long-Covid also faced the same reaction initially. Experts emphasized that Long-Covid and ME/CFS are similar post-infection syndromes, with some long-Covid patients even receiving ME/CFS diagnoses.

Vicky Whittemore, PhD, director of the NIH neurosciences division, shared, "Even as recently as 2015, when I got involved in overseeing grants on ME/CFS, there was still the perception that it was psychological." Dr. Whittemore continued, "All the blood work and imaging and other tests would come back normal, and people would be told there was nothing wrong with them and to go see a psychiatrist." However, Dr. Whittemore's concerns persist. Even with this newly described model of ME/CFS pathomechanism, pinpointing a specific biomarker or clinical test that can diagnose ME/CFS still requires further research efforts.

Moreover, one caveat is that this model is not proven. The authors themselves do admit their study is mainly correlational. Determining cause and effect for a disease with complex pathomechanism like ME/CFS would be a huge challenge. As it's unethical to induce these pathomechanisms to see if they cause ME/CFS in humans, we would need to rely on animal models. Even then, generalizing findings from animal research to humans would require a leap of faith.

One way forward is to investigate reverse causation via pathomechanism-directed treatments. Based on the pathomechanism model, the study authors have proposed immune checkpoint inhibitors or neuropsychiatric drugs—aimed at correcting immune exhaustion or brain neurochemical changes—as potential treatments for ME/CFS. If these treatments do indeed work, they would support the model's causative power.

All in all, scientists at the NIH have done brilliant work at establishing a starting point for ME/CFS research with their newly described pathomechanism or disease model of ME/CFS.

Lastly, if you have made it this far, thank you. Subscribe to my Medium email list here. You can also tip me here if you are feeling generous today, and I will appreciate any financial support I can get.

I started this draft nearly two months ago and finally got around to finishing it thanks to Medium's Draft Day.