عُدْنــا والعَـوْدُ أحْمَـدُ

While working as a penetration tester at BugSwagger on a web application engagement (target referred to throughout as ex.com), I habitually check the authentication and account-management endpoints early in the assessment:

1- reset password 2- change password 3- change email 4-account settings These areas are always juicy targets — a small design mistake there can lead to a major impact

On ex.com I started looking into the reset flow and the email-campaign endpoint that triggers the password-change confirmation. At first glance the UI looked completely normal: a reset email, a confirmation link, a form to set a password. But when I dug into the API, I found a critical server-side flaw: the endpoint accepted and acted on sensitive fields directly from client input.

That combination — Mass Assignment + insecure reset design — made it possible to perform a 1-click account takeover.

Below, I'll walk through what I found, why it matters, how it can be fixed, and how security teams can detect wider abuse.

Step 1: test the reset password page

"First, I tested the reset password page — it was working completely normal and didn't show any issues at all."

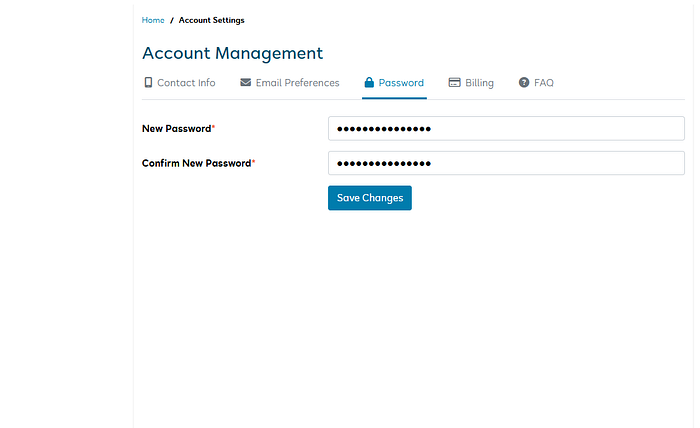

Step 2 : test the change password page

"While testing the change password page, I noticed something very important: when you try to change your password, the application asks you to enter the new password twice. This alone can open up several potential scenarios, such as CSRF. However, I decided to first take a closer look at the request structure before exploring those possibilities."

Step 2.1 : Normal Request Behavior

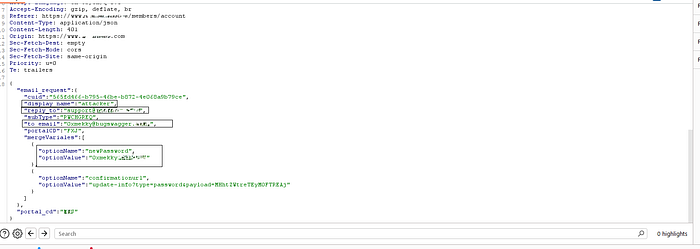

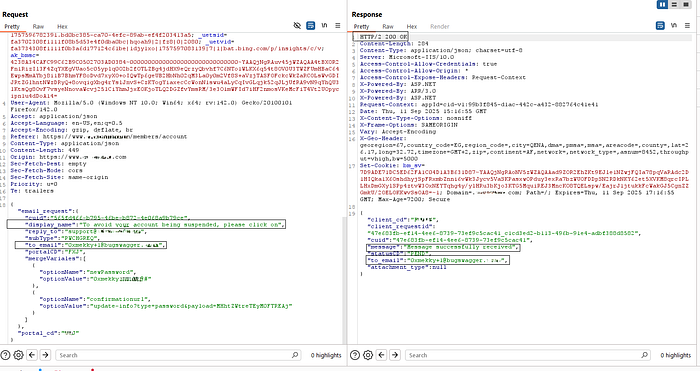

"I opened Burp Suite to inspect the structure of the request and see how things were working behind the scenes, in order to better understand the flow."

**"I entered a new password twice as required and intercepted the request. As shown in the screenshot below, the request contained the following parameters:

display_name: "account name"reply_to: "support@ex.com"to_email: "0xmekky@bugswagger"newPassword: [my chosen password]**

"The first thing that came to mind when I saw this request was to send it normally and observe the behavior. After sending the request as-is, I received the confirmation email in my inbox. At this point, I noticed something critical: as soon as I clicked the confirmation link, the account password was immediately changed to the new one I had supplied earlier. In other words, no additional input was required from the user — just a single click on the link was enough to complete the password reset."

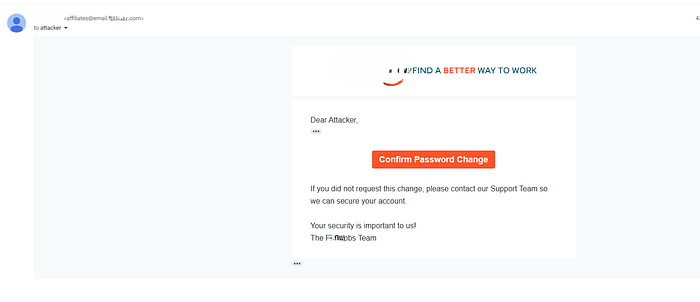

Step 2.2 : Manipulating Email Content

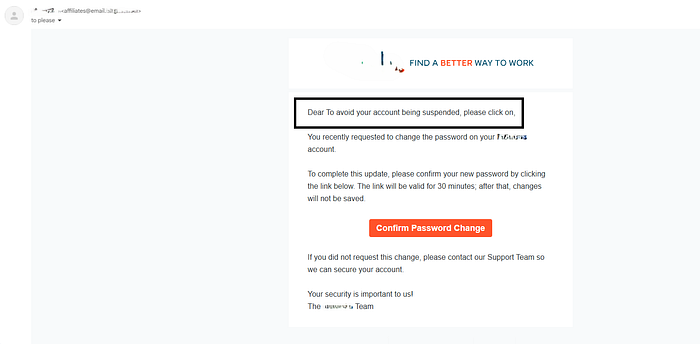

*"I also noticed something interesting in the confirmation email: the account name was being displayed directly in the message. That made me wonder what would happen if I changed the value of that parameter. So, instead of the actual account name, I inserted a custom message of my choice. For example, I replaced it with:

To avoid your account being suspended, please click on ...

After sending the modified request, I confirmed that the message was successfully reflected in the email. The manipulated text appeared exactly as I had crafted it, making it possible to insert arbitrary content into official system emails."**

display_name: "To avoid your account being suspended, please click on"Step 2.3 : Changing the Recipient Email

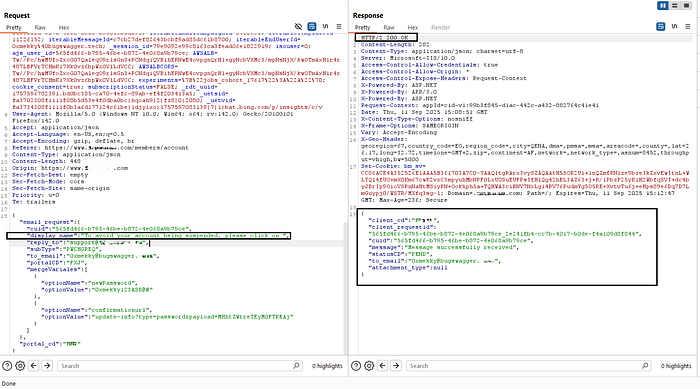

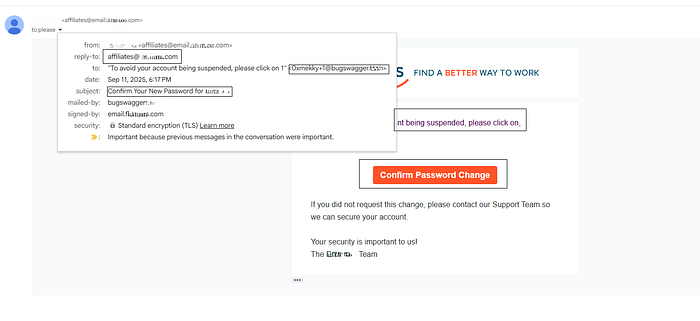

- *"Up to this point I was only testing against my own account. Next, I tried modifying the

to_emailparameter in the request. By default, it was set to my address (to_email: "0xmekky@bugswagger"). From the same account, I changed that value to another user's email — for example:to_email: "0xmekky+1@bugswagger"

The system accepted the change and delivered the password reset confirmation email to that address. The message looked completely legitimate, and when the recipient clicked the confirmation link, their account password was automatically updated to the attacker-controlled value — no additional input required.

When combined with the ability to manipulate the display_name field, this means an attacker could craft highly convincing reset emails containing custom social-engineering messages, making the entire flow both exploitable and believable."**

✅Combined Impact

By chaining these behaviors, an attacker could:

- Send password reset emails to arbitrary users.

- Inject social-engineering messages via

display_name. - Achieve instant account takeover once the victim clicks the link.