I come from a place where the water is so cruel it bites, where diving means digging a hole in the ice and surfacing with your eyelashes frozen shut. I began cold plunging to support my grandfather after doctors suggested it might help with his cancer-related joint pain. At first, we'd barely wade knee-deep. But I developed a knack for it, and soon enough, I was scuba certified and exploring the underlayers of frozen lakes.

Without proper mental and physical training, this kind of diving I do now could be a death sentence.

But sometime after another Arctic melt season and too many maps showing vanishing permafrost, I started craving a different kind of immersion. Warmer depths. Other currents. Diving has rewired something in me: there's a silence below the surface that reminds me of home.

That's how I found Raja Ampat.

First, a photo of limestone peaks cresting above turqoise waters like the humps of a dragon. Then a National Geographic listicle calling it a "must-see" for 2025 followed by a New York Times spread including it in its bucket list dream. And then — the other side of the coin. Deforestation figures. Mining maps. Legal loopholes. Suddenly, the most biodiverse marine ecosystem on Earth wasn't just a paradise. It was a frontline.

Because Raja Ampat — an archipelago in West Papua, Indonesia — is more than just the "crown jewel" of the Coral Triangle, the name scientists have given to this area of Southeast Asian seas that sustain the richest marine ecosystem on Earth. It's what the world stands to lose when we greenwash collapse.

UNESCO named it a Global Geopark in 2023. Over 2 million hectares of its reefs are protected. Its karst islands and coral-covered seabeds are so biodiverse they make other reefs look like deserts. In its villages, about 70,000 West Papuans live by the tides, navigating in wooden canoes, speaking over a dozen dialects. They call the forest mother, and the sea father. Even the view from Piaynemo Island appears on Indonesia's highest-value 100,000 rupiah note.

But currency comes with a cost.

As Raja Ampat's popularity continues to grow past NatGeo covers and New York Times travel recommendations, so do the threats to its future. By now, you probably know the equation: if humans show up, devastation follows. And this is more than increasing tourism, bringing major challenges of waste and sewerage management.

Indonesia now produces over half of the world's nickel, an essential ingredient of our "clean" future in electric vehicle batteries, and it's racing to supply two-thirds of global demand by 2030. And so, nickel mining is creeping into Raja Ampat. These are small islands, many of which are legally off-limits to mining. But the law hasn't stopped the drills. Or the heavy machinery from clearing forests. Or the few rivers that provide freshwater, clouded with tailings that eventually choke coral reefs. Or the communities being pushed to the edges of their ancestral lands.

What does a "clean" future look like when it runs on coal-fired smelters and the erasure of Indigenous worlds and ecosystems?

This is the paradox at the core of our so-called transition: that in the name of planetary salvation, we are industrializing paradise. In places where oars are still the most powerful technology, bulldozers now arrive to pave a battery-powered future.

Indonesia's nickel industry isn't just a case study in extraction — it's the poster child of tradeoffs.

And if Raja Ampat falls, what hope is left for the places that never made the front page?

The Cost Beneath the Chrome

Nickel isn't rare. But it is in high demand. And that difference — between what's abundant and what's profitable — has redrawn Indonesia's fate, leaving a trail of promises, pollution, and political amnesia.

So, again: in 2023, Indonesia produced over half of the world's mined nickel, and by 2030, it's expected to supply nearly two-thirds. The numbers sound impressive — until you realize what they're built on.

To transform the country into the world's EV nickel superpower, Jakarta banned the export of raw ore in 2020, requiring it to be processed on-site. That meant smelters. Industrial parks. Entire fossil-fueled cities rising along island edges. Today, these smelters are powered by coal-fired plants, built fast and dirty, baking the same climate they claim to be cooling.

The investment flood came quickly. Tens of billions of dollars, much of it from China, poured into Indonesia. Nickel towns sprang up across Sulawesi and the Maluku Islands, transforming nutmeg coasts and mangrove forests into devastated nickel belts. Behind every battery-grade nickel shipment is a scorched village, a hollowed mountain, or a reef that no longer breathes.

Indonesia, with the largest nickel reserves on Earth, feeds the supply chains of Tesla, Ford, Volkswagen, and nearly every major EV player on the planet. Elon Musk once begged miners to "please mine more nickel." Indonesia delivered. In 2023, Tesla inked a $5 billion nickel deal with the country, even as the headlines were filled with warnings of deforestation, coal pollution, and worker deaths.

Tesla changed its rhetoric. But it didn't change its sourcing.

And so the contradictions pile up. The smelters that purify nickel for "clean" cars are burning coal. The workers powering this revolution are dying in preventable fires. In Sulawesi, tailings dams have burst and drowned entire villages. Nickel-laced runoff flows into fisheries once teeming with life — now empty.

More than 75,000 hectares of forest have already been erased. A recent investigation found that a major Indonesian firm polluted a community's water source for over a decade — nickel compounds included. Harita Nickel, the firm in question, insists it's working to improve its environmental and social governance. Meanwhile, cancer rates and miscarriages are rising nearby.

And now, the industry is looking further east. To the islands with no room left to bleed.

Raja Ampat is legally protected by Indonesian law. Mining is banned on small islands like these. And yet, it's still happening.

The law is only as strong as the will to enforce it. And that will erodes fast when nickel's on the table.

The Impact Isn't Abstract

Indonesia stretches across nearly 20,000 islands. And by its own law, almost all of them — 99% — should be off-limits to mining. That's because they fall under the legal definition of "small islands," defined in Law №27/2007, which bans extractive industries on islands smaller than 2,000 km². The Supreme Court upheld the ban again in 2024. On paper, the law still stands.

But paper laws don't stop drills.

According to Forest Watch Indonesia, 245,000 hectares (or three New York Cities) across 242 small islands have already been handed to mining companies. From Obi Island to the vast IWIP and IMIP industrial zones, the nickel boom has ignored boundaries, bulldozed rights, and replaced conservation with combustion.

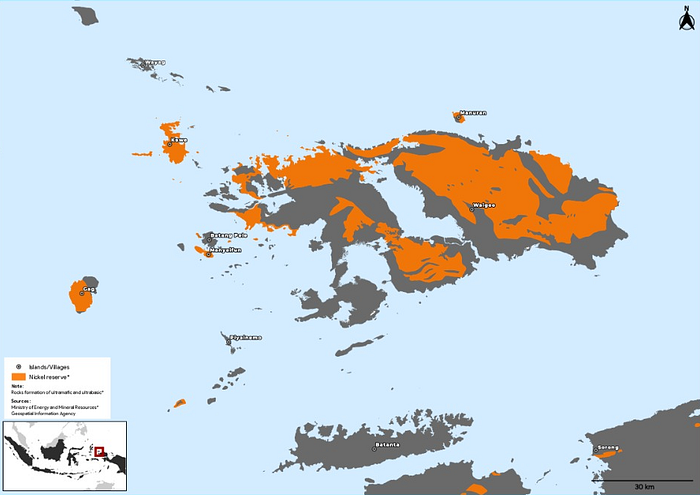

For years, industrial mining in Raja Ampat was kept at bay — largely confined to three smaller, mineral-rich islands: Gag, Kawe, and Manuran. But what began as isolated projects has metastasized. Between 2020 and 2024, land use for mining in Raja Ampat grew by nearly 500 hectares — triple the pace of the five years prior.

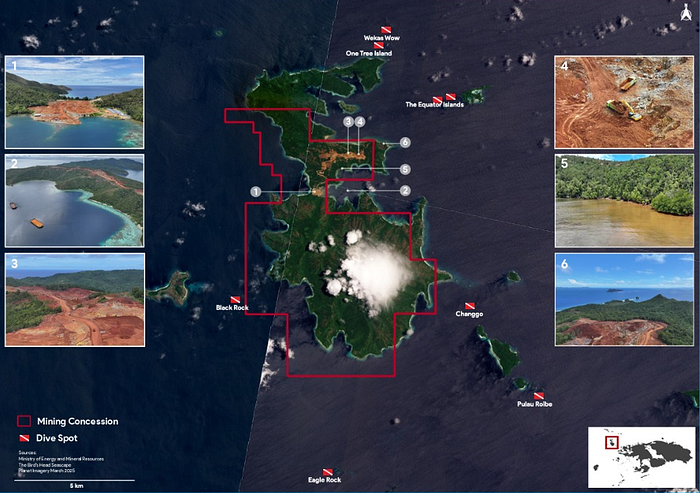

In February 2025, the warning signs turned into footprints. PT Mulia Raymond Perkasa — a company few locals had even heard of — set up a base camp on Batang Pele. The license had been quietly granted back in 2013, but no one had moved until now. First, men came with machetes to cut a trail through the forest. Then came the surveyors. Then the buildings. The location: dangerously close to key diving sites, family-run eco-lodges, and a marine ecosystem that's still recovering from last year's bleaching event.

A few weeks later, a fresh 3,000-hectare nickel permit appeared on the government's mineral data portal. This one, on Waigeo — home to endemic birds of paradise, the island that gave Raja Ampat its name.

The Indonesian government revoked four licenses on June 10, 2025, after mounting public pressure. But the impact isn't abstract. You can see it all the way from Google Maps. Near jetties and old homestays, the water has changed color. And these revocations may be temporary. Because a concession revoked today can be reissued tomorrow, especially when there's nickel underground.

The Two Faces of Kawe Island

A pristine tropical island — crystal clear waters, black coral gardens, and majestic manta rays gliding through the currents. This was Kawe Island, a hidden gem in Indonesia's Raja Ampat region. No tourist resorts, just pure nature at its finest.

Then, the mining began. From above, the island now bears a scar. The mining company literally carved through the island's center, turning lush forests into bare dirt and sending muddy runoff bleeding downslope toward the reef. A line of dirt cuts through the forest's waist, nearly slicing Kawe in two. This isn't a metaphor. It's a mining permit that took a beautiful painting and decided to cut it right down the middle.

A 5,992-hectare concession, larger than the island itself, had been quietly handed to PT Kawei Sejahtera Mining (KSM) — a company founded by a politically connected figure in West Papua. Mining has occurred on and off since at least 2004. The most recent license was awarded in 2013 and would have allowed operations until 2033. It extended not just over land, but into the surrounding reefs — some of the most biodiverse marine habitats on Earth.

The damage, of course, goes beyond just looks.

Fishers say the bay is now empty. Divers say the water tastes like rust. Scientists warn that Kawe's steep slopes and heavy rains are a lethal mix. Each downpour sends sediment into the shallows, choking coral. Even the manta rays, which rely on this area as an essential "highway" for their migration, are struggling to survive in these changed waters.

Despite public outcry leading to the mine's closure in June 2025, the story isn't over. Behind the scenes, powerful figures — including a former navy admiral and influential business leaders — have stakes in this operation. The links run deep. So do the consequences.

The island now stands as a symbol of this conflict: parts still showing the beauty of untouched nature, others scarred by mining. One, a sanctuary. The other, a sacrifice. Both real. Both bleeding into each other. And if the mining resumes — and it likely will — the cut will keep deepening until there's nothing left to split.

This is How to Kill a Coral Reef

Nickel mining doesn't just gouge out land. It unravels entire ecosystems.

Indonesia's laterite ore lies close to the surface — cheaper to reach, harder to refine. Unlike the deeper, higher-quality sulfide deposits in Russia, Canada, or the U.S., processing laterite nickel requires intense heat, more chemicals, and more coal. The fastest way to get it out? Strip mining. No tunnels. No restraint. Just chainsaws, bulldozers, and a race to the bottom.

In a rainforest, this means cutting down everything. Piling the topsoil into loose mounds. And watching it bleed.

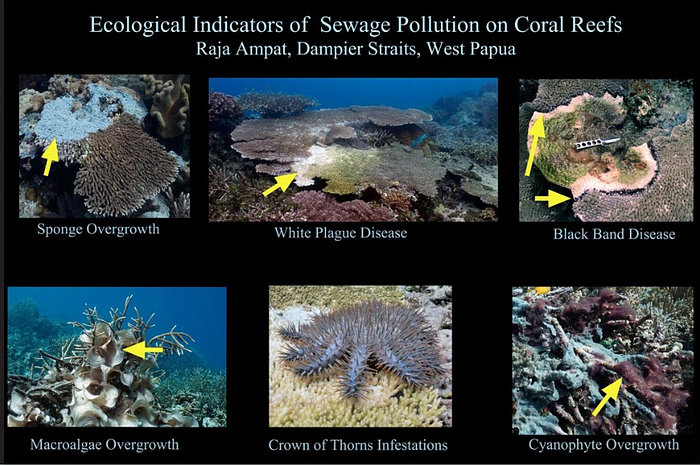

Under Indonesia's tropical rains, exposed earth turns into runoff — muddy, acidic, and loaded with metal particles. That slurry spills into rivers and the sea. And when it hits the coast, it smothers coral. It buries reefs. And it feeds algal blooms that choke out what's left.

Corals don't just die. They suffocate.

Studies confirm that sediment runoff is among the deadliest threats to reefs. It strips away light, invites disease, and accelerates death. In Raja Ampat, it's already happening. Forest to sea, mine tailings now spill like dirty ink into once-pristine waters. What's buried beneath that silt is the very foundation of life offshore.

Coral reefs make up less than 1% of the ocean floor. But they support one-third of all marine life and sustain over a billion people with food, jobs, and protection. These are not decoration. They're infrastructure. And they're collapsing.

We are living through the worst global coral bleaching event ever recorded. Ocean heat, like a subaquatic wildfire, has surged year after year — 2023, 2024, and now 2025 — erasing the last of the "resilient" zones. Even once-secure sanctuaries like the very Raja Ampat and Eilat have bleached.

Reefs don't scream. They just turn white. And then they disappear.

Today, nearly half of all coral species face extinction. And yet the machines keep digging.

The irony is that even as the reefs collapse, the government is ramping up its push to bring more tourists to the "last paradise." In 2024, over 33,000 visitors came to dive and sleep in stilted homestays run by local Papuan families. But paradise has a plumbing problem.

In a region with no waste infrastructure, garbage, untreated sewage, and chemicals flow directly into the sea — from homestays, resorts, liveaboards, and the villages themselves. Toxic cyanobacteria are blooming. Coral is suffocating not just from heat, but from soap and shit.

Mangroves die just the same

Raja Ampat's tropical ecosystem is deeply interconnected — from sea to land and everything in between. This is especially true of the mangrove forests that ring the islands.

Mangroves don't make headlines. They don't bleach like coral. They don't scream when bulldozers roll in. But they're everything. They're flood barrier and fish nursery. Carbon sink and storm shield. Grocery store and pharmacy. For many Papuan families, the mangrove is dinner, shelter, and history braided together in roots and silt.

And now, they're vanishing.

60% of the mangroves around Gag and Kawe are already gone. Globally, more than half of all mangrove ecosystems are on track to collapse by 2050. Local groups like the Raja Ampat Coastal Friends Association have been sounding the alarm for years. Restoration efforts tried to replant. But the soil is drowning in slurry. Roots can't breathe in mud.

But the Indonesian government says otherwise.

On a June 2025 visit to Gag Island, the Director General of Mineral and Coal, Tri Winarno, claimed there was "no sedimentation in the mining area." No sediment, despite video, photos, satellite imagery, and entire villages watching their lifeline sink into sludge.

Corporate denial faking an environmental review.

The sediment is there. You can see it. Destroy the mangrove, and you don't just erase trees — you take away the kitchen and the safety net.

The hotel industry is worried. So are the families who rely on tourism. Homestays like those supported by Stay Raja Ampat aren't just side hustles. They're survival strategies. Lose the reef (and the mangroves), and you lose the reason anyone comes. You lose the income. You lose the future.

Imam Shofwan of JATAM says the quiet part out loud: "Your electric vehicle kills us. They say this is the solution to the climate crisis. In the field we have found that this is the new coal. They do open pit mining, and they are highly dependent on huge amounts of coal for processing… For us this is the fake energy transition. The government's apparent revocation of mining permits happened because of the strong pressure from the public, not because of the goodwill of the government."

Paradise Is the Price Tag

This is the paradox no one wants to name: in the name of saving the planet, we are industrializing paradise.

The math is brutal. In places where oars are still the highest form of technology, 10,000-tonne barges now plow through dolphin corridors. Ships blast sonar across seagrass nurseries. 7,000 metric tonnes of nickel ore dumped onto coral. Mangroves smothered under corporate sludge. Fishing boats pushed farther offshore, burning more fuel to catch fewer fish.

This is the business model.

The Indonesian "omnibus law" stripped away Indigenous consultation and rolled out the red carpet for "strategic projects" — code for mining without consent. Divide-and-conquer tactics split communities. A few signatures unlock a permit. A company arrives. And paradise begins to vanish.

In theory, all of this is progress. In practice, it's the same colonial logic, dressed up in nickel and green PR. In the name of saving the planet, we are industrializing paradise.

This is the poster child of our energy transition: not an honest reckoning with consumption, but a sleight of hand. It's like sweeping dirt under a rug — the mess isn't gone, it's just hidden. While there's good in the transition to "eco-friendly" cars, communities in other parts of the world are dealing with the mining, pollution, and environmental destruction needed to make those cars possible.

Meanwhile, the world keeps mining — not for need but for margins. For supply chains bloated with overproduction. For electric SUVs heavier than tanks, and homes stacked with devices we'll ditch next year. The truth is that we already have the transport, logistics, and energy systems to slash emissions — without razing the last rainforest island sanctuaries left on Earth. But it would mean choosing less. Or better: choosing enough.

Because the world isn't dying from lack. It's dying from excess.

All Raja Ampat needs is to be left alone. Its reefs, mangroves, and mountains already regulate the planet better than any machine we've built. The tragedy is that we've forgotten how to value anything we don't dig up and sell.

I'd love to go. To dive through Eagle Rock's manta highways. To sleep in a stilted homestay and hear the forest speak. But I worry that if I did, I'd be stepping into the very trap I'm writing about — one more person drawn to the myth of untouched beauty, becoming part of the pressure that makes it disappear.

This is happening to us. We are the demand. This is our transition. And unless we break from the lie that "clean" means different but still more, Raja Ampat will not be the last paradise lost. It will be another one that vanished from the "must-see" bucket list.

May the northern lights guide you, M.