Take a train journey through the British countryside, and you're sure to come across a view like the one in the photo above. When fields full of solar panels — known as solar farms or solar parks—started to become common around 10–15 years ago, I used to gaze out on them with a mix of hope and excitement — they offered tangible, irrefutable evidence that the renewable energy transition was underway. But while I still welcome the sight, as they became more ubiquitous I get a karmic pang of guilt, as more and more productive farmland is put out of action. Food security, food price inflation, and the benefits of eating locally and seasonally, are all negatively impacted as farmland is given over to other uses, no matter how great those uses are.

But there is another way: agrivoltaics. In other words, letting livestock graze — or crops grow — between the rows of solar panels. Can we really do both? Can we have/grow our climate cake and eat it?

Amazingly, the term agrivoltaics was first coined in a 1982 paper by academics in West Germany, proposing "a configuration of a solar, e.g., photovoltaic, power plant, which allows for additional agricultural use of the land involved". Fast forward over 40 years, and Goetzberger & Zastrow's vision is very much a reality.

"Combining solar energy with agriculture seems like a very sensible idea, especially… where competition for land is fierce," says Martijn van der Pouw, business developer for Statkraft, an agrovoltaics company in the Netherlands. "There are several solar parks where sheep graze between the panels, but this is not what we in The Netherlands would normally consider agrivoltaic combination use. It's just an easy way for greenkeeping. In an agrivoltaic project, the goal is to produce high-quality fodder, vegetables, berries, or fruits, while also producing energy." He advises that the primary focus should be on agricultural production, with solar filling in the gaps — not the other way around. "A general goal is that agricultural production should be at least 70 per cent of what it was before the solar panels were installed," says van der Pouw.

At first glance, it might seem like trying to do both together means compromising the food and energy production — that you end up doing neither as effectively as if you kept them separate. In fact, there's evidence that both benefit. PV panels work optimally at cooler temperatures (between 15C and 35C), so installing them above or between evapo-transpiring crops has temperature-regulating properties that keeps them cooler and more efficient (which is also the case with solar shading over canals and reservoirs — another effective dual-use, land-saving option).

In return, growing certain crops in the shade of solar panels can produce better yields, too. One study from the University of Arizona found that agrivoltaic systems led to two-to-three times more vegetable and fruit production than conventional agriculture. The study, published in Nature, presented results from a multi-year research project using chiltepin pepper, jalapeno and cherry tomato plants: the results showed that shading from the panels had a positive impact on air temperature, direct sunlight and atmospheric demand for water, stating:

"The shade provided by the PV panels resulted in cooler daytime temperatures and warmer nighttime temperatures than the traditional, open-sky planting system… There was also a lower vapor pressure deficit in the agrivoltaics system, meaning there was more moisture in the air."

Protection from sunlight and hot temperatures offered by solar panels enabled a better harvest for all three crops — up to three times greater for chiltepin fruit production and two times greater for tomatos. Given the famously tight margins faced by farmers, these are huge benefits.

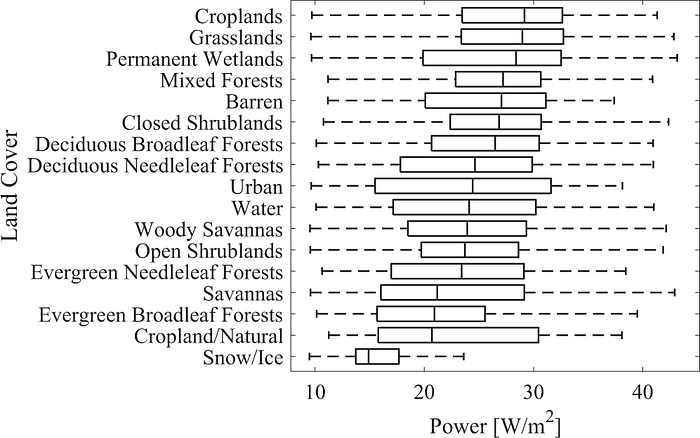

Agrivoltaics and the benefits of shading make intuitive sense in a desert location like Arizona. But what of cooler states and countries where a lack of sun, not shade, is more of an issue? A study by Oregon State University, also published in Nature, found benefits in more temperate grasslands and wetlands. Barren terrains, traditionally preferred for solar PV farms, were in fact found to be less suitable.

Baa Baa, Solar Sheep

As a reluctant vegetarian, who stopped eating red meat for environmental reasons, I'm always looking for a loophole. Culled wild venison, deemed a pest in the UK, for example, is an occasional treat. So, what of the livestock grazing option that van der Pouw dismissed as merely woolly lawnmowers? Could agrivoltaics bring lamb shank back onto my Easter dinner table?

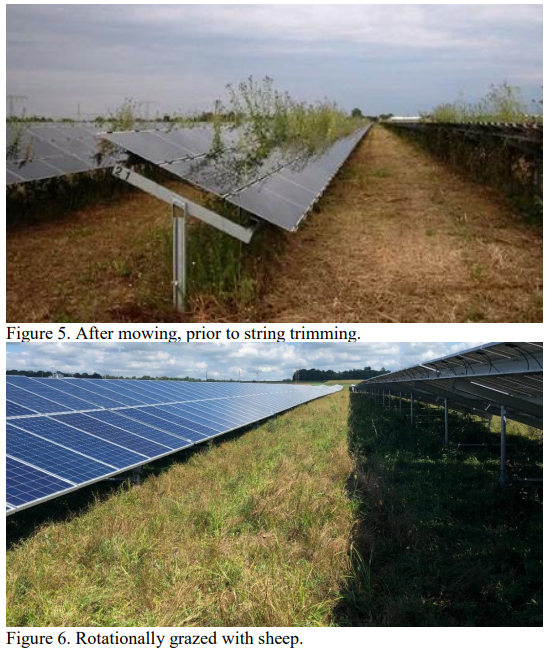

Research reported in The New Scientist finds that sheep living among rows of solar panels spend more time grazing, benefit from more nutritious food, rest more and experience less heat stress, compared with nearby sheep in empty fields. Another study from Cornell University, covering 14 sheep-grazed solar farms, suggests that agrivoltaic farms also offer more efficient renewable energy at lower overhead costs, as well as reducing wildfire risks. In particular, grazing sheep on solar sites proved a cost-effective method to stop weeds growing up and over the panels, casting shade that prevents solar energy production. The study paper includes the following extraordinary before and after photo:

Standard Solar, a renewable company with more than 350 megawatts of US solar, uses sheep grazing beneath its panels in the Midwest and New England, finding it especially useful on rocky sites. "You have to cut the grass because it's a fire hazard," Jay Smith, director of asset management at Standard Solar, told Bloomberg. "The sheep do a better job supporting the biodiversity than a conventional mower." As well as sheep providing meat for local markets, they are a fibre source too: Bloomberg also reports of a Minnesota-based shepherd Josie Trople whose "solar wool" hats and socks from her agrivoltaic sheep now make up a fifth of her revenue. There's even a potential carbon-sequestration upside, with solar sites with episodic grazing displaying better carbon storage and nutrient density in the soil.

It's slowly catching on in the UK too, though I'm yet to see it out of my train window. According to written evidence to the UK Government's Environmental Audit Committee's inquiry in January 2023, a company which monitors around 10% of all large (over 3MW) solar farms in the UK stated that 38% of its sites were grazed by sheep to some extent, while one of Solar Energy UK's larger members said that approximately a third of its portfolio is grazed. The member, who preferred not to be named, stated they would "much prefer it to be around 50%" for ecological and economic reasons, adding that there was "definitely plenty of interest" from shepherds. The barriers to adoption included low panel heights and off-putting paperwork. But any concern over infrastructure damage from sheep was seen as "readily avoidable, simply through installing guards around cabling".

In this year of vital climate elections, solar farms — like many progressive movements — risk falling to the sword of the 'culture wars'. The UK's current Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, keen to win favour with the rural electorate, released the following tweet in summer 2022:

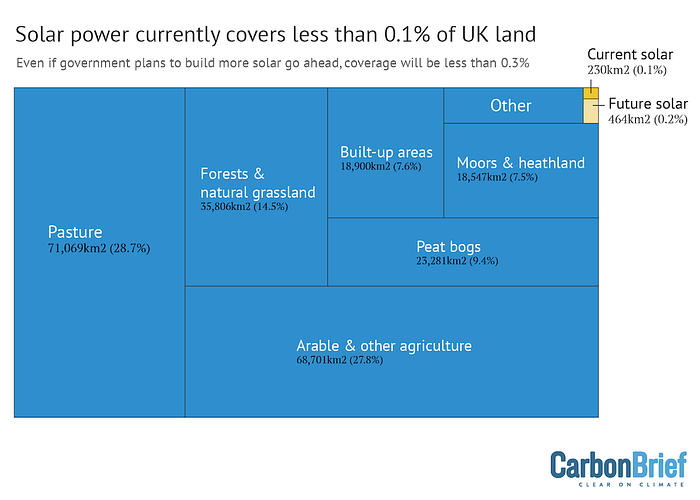

In 2022, Carbon Brief estimated that existing solar farms made up just under 0.1% of land in the UK or 230km2, compared to agricultural land covering 56–70% of the UK with 70,000km2 as pasture for grazing cows and sheep, and around 67,000km2 is for growing cereals and legumes. If these really are in competition, then it's hardly a fair fight. And 'swathes', as the tiny speck of yellow in the infographic below attests, is clearly a gross overstatement.

In attacking solar farms, however, culture wars warriors may have mis-read which side they are fighting. The evidence suggests that most people in the UK, including 73% of Conservative party members, back agri-solar projects. To the rural farming community (traditionally, though by no means exclusively, right-leaning) this offers an additional revenue stream that works alongside — not instead of — traditional farming practices. The powerful National Farmer's Union explains that, rather than directly opposing solar, it is now:

"…working with the solar industry, ecological consultants and other stakeholders to ensure that good practice guidance is applied to this next wave of solar farm construction, enabling truly multi-purpose land use as a source of diversification income for farmers at a time of significant uncertainty for our industry."

Agrivoltaics, then, could well be the ultimate climate win-win. Have you seen any examples near you? And why isn't this mainstream practice yet amongst solar companies or indeed farmers? I'd love to hear your thoughts in the comments below. In the meantime, I don't think I'll be munching on mutton again any time soon — but I do fancy a pair of 'solar wool' gloves next winter. I just need to find where they are in the UK first.

Published in The New Climate. Follow for the latest in climate action.