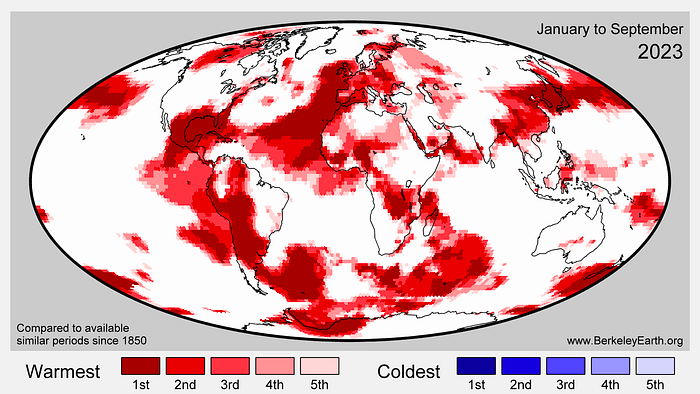

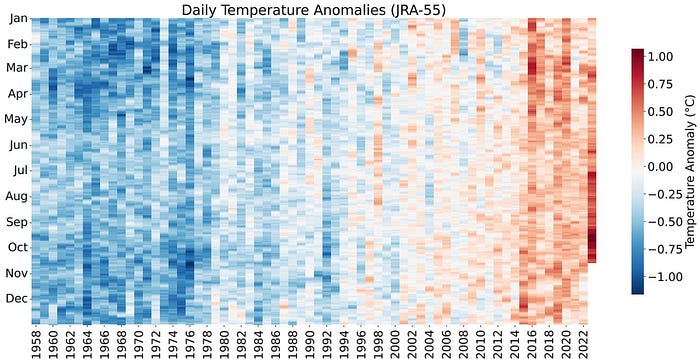

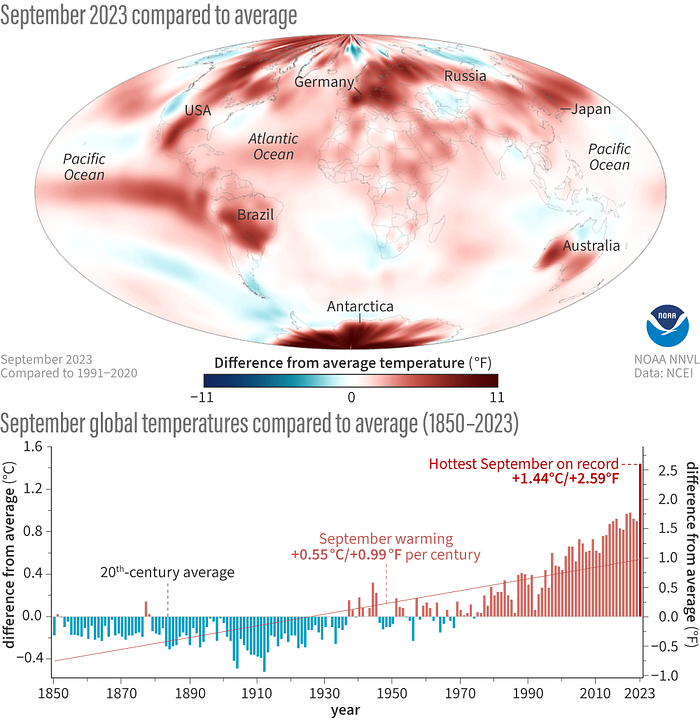

After a cooler start to 2023, four months have seen unprecedented global temperatures, with September being the hottest month ever recorded. But sweltering temperatures baking the globe on land and sea have been piling up month after month, year after year. September was in fact the 6th straight month with record global ocean temperatures, and the 49th straight September with temperatures higher than the 20th-century average; oh, and the 535th consecutive month with warmer-than-average temperatures.

This meteorological evolution saw the likelihood of 2023 becoming the warmest year on record jump from 46.8% at the end of July to a 99% "virtually certain" probability by Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) standards.

But this isn't just another apocalyptic prediction. It's a stark reality, proven by empirical data. And one that demands our immediate action.

New Record Becomes Clear Against Not-So-Grim Earlier Predictions

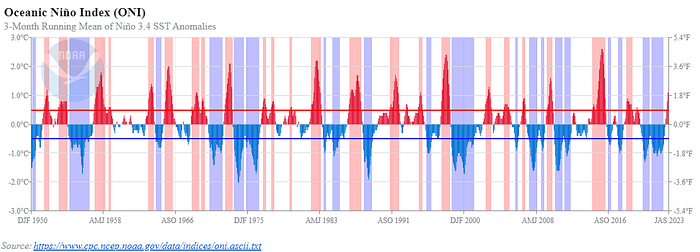

In a year that began with uncharacteristic coolness, projections from renowned authorities such as NASA's Dr. Gavin Schmidt, the UK Met Office, Berkeley Earth, and Carbon Brief suggested that 2023 could only be one of the top ten warmest years on record. And the early months of 2023 witnessed temperatures subdued by an unusually persistent triple-dip La Niña event, causing global temperatures to remain lower from late 2020 through the onset of this year.

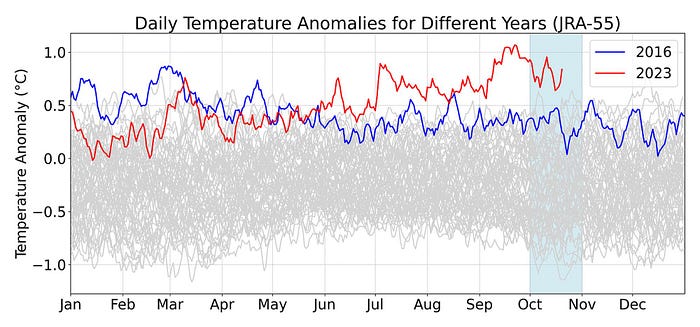

But starting in March, conditions in the tropical Pacific began to transition rapidly into what is shaping up to be a strong El Niño event, even though global temperatures tend to respond around three months after peak El Niño conditions. Since then, a pattern of monthly temperature records has become the trend. And after the past two months, it has become unambiguously clear that 2023 will be the hottest year on record.

Because September was the warmest month ever recorded in the 174 years of NOAA's instrument records. With a temperature anomaly of 1.44°C (2.59°F), it surpassed the previous record for September by 0.46°C (0.83°F) and the prior record anomaly, dating back to March 2016, by 0.09°C (0.16°F). This record-breaking warmth enveloped a substantial 20% of the Earth's surface, marking the largest such coverage since at least 1951. In stark contrast, less than 1% of the globe experienced a record-cold September.

"Not only was it the warmest September on record, it was far and away the most atypically warm month of any in NOAA's 174 years of climate keeping," said Sarah Kapnick, NOAA's chief scientist, in a statement.

And with October's data mainly accessible in the JRA-55 real-time reanalysis product, estimates by climate scientist and energy systems analyst Zeke Hausfather suggest that October 2023 is on track to become the warmest October on record by at least 0.3°C. This peak won't be quite as extreme as September's anomaly. It will still come in as the second-highest anomaly of any month on record.

Everyone Agrees: Hottest Year Across All Records

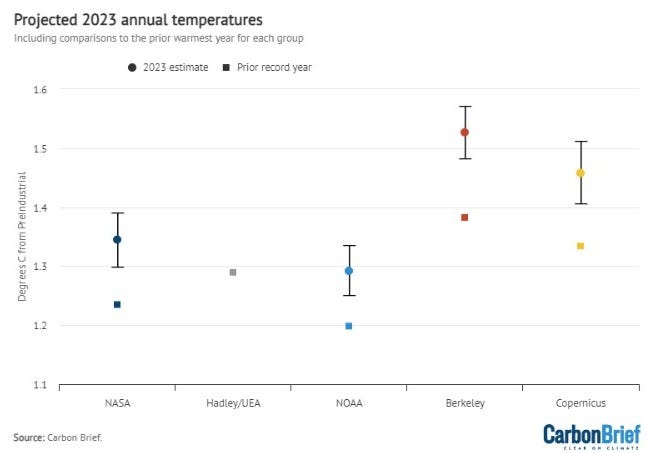

So, the table is set, and every temperature dataset converges on a shared prognosis: 2023 is poised to eclipse 2016 as the previous hottest year — unfortunately, one of those records you don't want to break. Based on the temperatures over the first ten months of the year, propelled by a combination of current El Niño conditions and projected El Niño conditions for the rest of the year, Carbon Brief estimates where each distinct surface temperature record is likely to conclude.

The expected temperature increase in 2023 concerning pre-industrial conditions manifests in varying degrees across these datasets. The central estimates span from 1.29°C (NOAA) and 1.35°C (NASA) above pre-industrial levels (1850–99) to 1.46°C (Copernicus) and 1.53°C (Berkeley Earth).

The choice of data and the methodology for filling gaps between observations wield significant influence over the resultant temperature figures. And differences in the ocean dataset utilized also contribute to divergences.

But one thing is clear: 2023 will be like no other year, climatically speaking.

Between The Lines — What Does it Mean?

First of all, it is important to understand that surpassing the 1.5°C threshold in a single year is not equivalent to a breach of the 1.5C warming limit in the Paris Agreement, which refers to long-term human-induced warming, excluding the annual temperature fluctuations influenced by natural climatic variations, such as El Niño.

Nonetheless, the alarming rise in temperatures has ignited intense scientific speculation, albeit yielding few definitive conclusions, regarding the variety of factors contributing to extreme global temperatures, along with the obvious long-term accumulation of human-caused climate change.

But does this acceleration suggest that global warming is outpacing predictions?

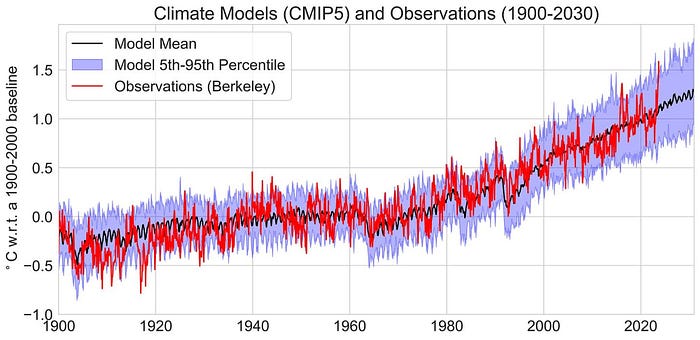

While there is compelling evidence indicating an augmented rate of warming in recent decades compared to what we've experienced since the 1970s, this acceleration has been largely incorporated into current climate models. These models project approximately 40% faster warming between 2015 and 2030 than from 1970 to 2014.

The more intriguing question is how temperatures in recent years and months measure up against climate models' projections for this timeframe.

It is essential to exercise caution when interpreting a single month that exceeds the model's range. Such instances have occurred previously, particularly during significant El Niño events like 1998 and 2016. In fact, we should anticipate approximately one in 20 months surpassing the 95th percentile range if models are indeed an accurate reflection of real-world variability.

It's noteworthy that we are still in the early stages of the current El Niño cycle. Presently, 2023 bears greater resemblance to 1997 or 2015 than the previously recorded warm years, 1998 or 2016. It remains uncertain whether we will encounter more extraordinary warmth later in the year and early next year as the El Niño event peaks or if this El Niño follows a different course — potentially contributing more warming due to the swift transition from unusually persistent La Niña conditions.

NASA climate scientist Gavin Schmidt emphasized, "What's remarkable is that these record values are happening before the peak of the current El Niño event, whereas in 2016, the previous record values happened in the spring, after the peak."

The conclusion after an evaluation of both models and observations is straightforward: despite the extraordinary global temperatures observed since March 2023, these observations broadly align with climate model projections for this year, though this alignment may change as the current El Niño continues to evolve.

Carbon Budgets On the Brink

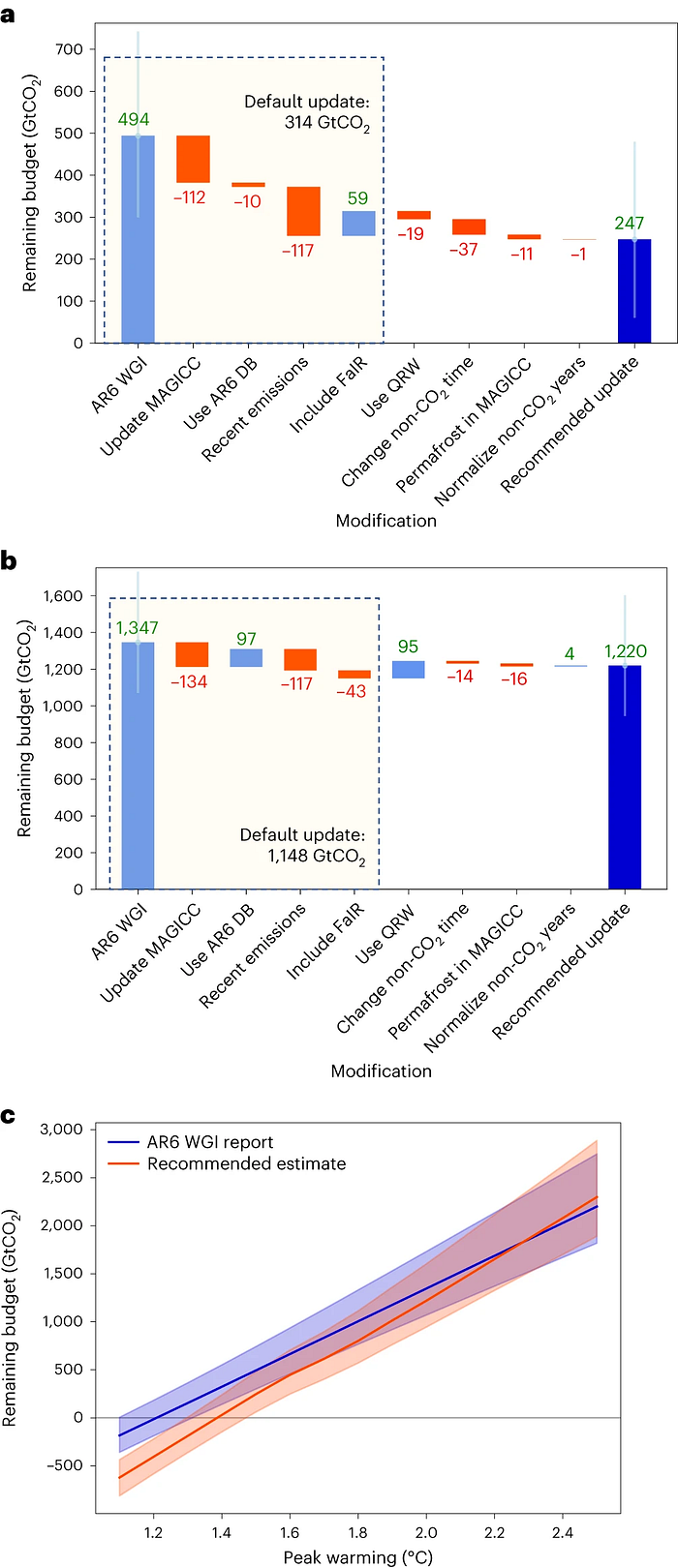

To estimate how soon we'll hit the 1.5°C warming target set by the Paris Agreement, scientists devised a carbon "budget" — the amount of carbon we can emit before breaching this critical threshold.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) predicted that we could emit only 500 billion tonnes of carbon to have a 50% chance of staying below 1.5°C. With current emissions at about 40 billion tonnes annually, the IPCC warned we'd cross the line by the middle of the next decade.

But a new study suggests it's even sooner. IPCC's data only extends to 2020; the researchers accounted for emissions beyond 2020. It also reevaluated the role of other warming factors, like aerosols, which exert a considerably more powerful cooling influence than previously understood by reflecting sunlight back into space. Yet, as efforts to improve air quality in urban areas and reduce the use of highly polluting fossil fuels progress, the number of aerosols in the atmosphere diminishes. Oh, and which mainly arises from the burning of fossil fuels.

According to the researchers, this re-evaluation of aerosols alone deducts 100 billion tonnes from the remaining 1.5°C budget. When combined with the additional carbon emissions and other minor adjustments, the total remaining budget dwindles to 250 billion tonnes.

Dr. Robin Lamboll from Imperial College London, the lead author of the study, emphasizes, "The window to avoid 1.5°C of warming is shrinking because we continue to emit and because of our improved understanding of atmospheric physics. We now estimate that we can only afford to release about six years' worth of current emissions before we are likely to exceed this key Paris Agreement reference point."

The researchers assert that to avert exceeding 1.5°C, global carbon dioxide emissions must reach net zero by 2034, a considerably earlier target than the current expectation of 2050.

Prof. Joeri Rogelj, also from Imperial College London, comments, "Having a 50% or higher likelihood that we limit warming to 1.5°C, irrespective of how much political action and policy action there is, is currently out of the window. That doesn't mean that we're spinning out of control to three or four degrees. But it does mean that the best estimates suggest that we will be above 1.5C of global warming."

The Dual Specter of War and Climate Crisis

The World Bank has issued a stark warning that if the war between Israel and Hamas escalates into a full-scale Middle East war similar to events from the Yom Kippur War of 1973, it could result in a significant shortage, driving the price per barrel to surge by 56% to 75%, reaching levels between $140 and $157, up from the current status of about $90. The previous peak, unadjusted for inflation, was $147 a barrel in 2008.

Add the ongoing Russia's war with Ukraine, which continues to affect the global economy, and the global economy could face a dual energy shock if the situation in the Middle East escalates.

The World Bank's assessment also indicated that the consequences of an escalating conflict would extend beyond energy prices. It could lead to a severe food crisis affecting hundreds of millions, increasing food prices.

As of now, the Israel-Hamas war has had a limited impact on commodity prices. While oil prices have risen by approximately 6%, other commodities like agricultural products and industrial metals have remained relatively stable. However, the situation could quickly worsen if the conflict intensifies.

It's commonly said that "the Stone Age didn't end for want of stones." Similarly, the age of fossil fuels is not ending because we've run out of fossil fuels (yet). However, the overwhelming evidence points towards a necessary shift. Fossil fuels present a severe threat to our current reality and our sustainable future. This includes our dependency on extraction countries, the intricacies of commodity pricing, and its impact down the food chain, all while renewable energy sources and electric vehicles are rising. Even within the fossil fuel industry, there has been a turning point, with oil companies such as Chevron conceding in court that "fossil fuels are the problem," despite their previous attempts to portray themselves as part of the climate solution.

The question we must confront is whether we need two simultaneous devastating conflicts across continents to drive the profound, systemic change that our world urgently requires. It certainly appears so.

Against these geopolitical crises, the Earth's thermostat continues to rise, with distressing occurrences like thousands of fish washing up dead in the Gulf of Mexico (see above) due to overheated waters, unpredictable tropical storms escalating into category 5 hurricanes, and alarming glacier melt rates.

The dual specter of war and climate crisis should serve as a stark reminder that the status quo is unsustainable. The imperative for systemic change has never been more apparent.