A jetski roars past a gasping four-wheel-drive, its snorkel barely breaking the surface of the engulfing tide. Behind it, a wooden canoe battles the surging currents, reaching its unlikely destination: a crumbling concrete wall. Its captain, undeterred, rescues a terrified dog clinging desperately for life. Above, the ominous hum of helicopter blades offers a fleeting promise of hope.

Yet, the merciless brown tide continues its assault.

This scene could be ripped from the pages of a dystopian science fiction novel, but it's the grim reality that has gripped Brazil for the past week. Torrential downpours have unleashed a flood of biblical proportions upon Rio Grande do Sul State, accounting for 70% of the month's typical rainfall. The resulting floods have eclipsed the historic deluge of 1941, with water levels in some cities reaching heights unseen in nearly 150 years of record-keeping, cutting off towns with raging floods and mudslides.

But one thing's for sure — we won't have to wait 150 years for the next one. Ane Alencar, science director for the Amazon Environmental Research Institute, told the Associated Press that the oscillating pattern of extreme drought-extreme rain was likely "the new normal."

Alencar's words were spoken before the current catastrophic flooding that has left people and even horses trapped on rooftops, hoping to be rescued.

"I don't know where my family is"

The downpour started on April 27. The water level rose dramatically, and it went on for over a week. The deluge of rain swelled rivers across the Rio Grande do Sul's low-lying Central Valley region, impacting more than half of its 497 cities. The infrastructure couldn't handle it — bridges collapsed, roads became impassable, and mudslides rampant. With no electricity or communication, entire towns were left in the dark.

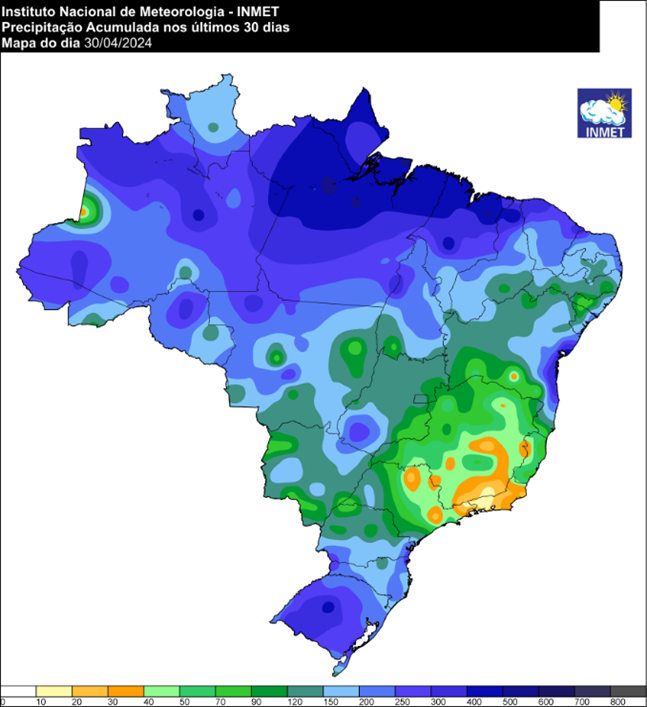

According to the National Institute of Meteorology, INMET, rainfall in certain areas exceeded 300 millimeters (11.8 inches). This caused the collapse of a hydroelectric dam (a second dam in the area also at risk of collapsing) near the city of Bento Gonçalves, where the volume reached a lethal 543.4 mm. The floods have also impacted water and electricity services, with more than 1.4 million affected overall, according to Brazil's Civil Defense.

President Lula Da Silva said, "Never before in the history of Brazil had there been such a quantity of rain in one single location."

Porto Alegre, the regional capital housing over 1.3 million people, saw 258.6 mm of rainfall in just three days. That's over two months of rain when compared to the Climatological Normal for April (114.4 mm) and May (112.8 mm). And so, the Guaiba River has hit a record level of 5.33 meters (17.5 feet), surpassing the record of 4.76 meters and causing widespread flooding and submerging neighborhoods, power plants, and even stadiums. The international airport, no wonder, has suspended all flights for an undetermined period.

The number of people left homeless is well past 150,000 and rising. I won't go into the death toll, but you can imagine. According to Brazil's Civil Defense, over 1.4 million people have been affected by flood-related disruptions to water and electricity services.

"We've been without food for three days, and we've only just got this blanket. I'm with people I don't even know, I don't know where my family is," said citizen Ricardo Junior.

'A disastrous cocktail'

The period between the end of April and the beginning of May 2024 is still influenced by El Niño.

The state of Rio Grande do Sul sits at a hotspot where tropical and polar air masses often collide. Pair this with El Niño, responsible for warming surface waters close to the equatorial belt in the tropical Pacific, and the atmosphere becomes a "disastrous cocktail" of hotter-than-average temperatures, high humidity, and strong winds.

This year, El Niño's consequences have been devastating, causing a historic drought in the Amazon after 11 months of record monthly temperatures — and counting. This comes after a series of environmental catastrophes in Rio Grande do Sul, with floods in July, September, and November 2023 already claiming lives. The September cyclone followed over two years of relentless drought, leaving the region parched.

These recent torrential rains mark the fourth environmental catastrophe in less than a year in the region, following floods in July, September, and November 2023, after over two years of relentless drought.

State Governor Eduardo Leite had described the recent floods as "unprecedented" and that "the state will need a sort of "Marshall Plan" to be rebuilt."

Long-term projections suggest that Rio Grande do Sul is set for more annual rainfall and extreme weather events, meaning more intense and damaging storms. According to research by NOAA, the ever-changing El Niño and La Niña weather cycles add "another degree of complexity" to understanding how climate change will affect future weather patterns. Currently, this phenomenon affects around 40 to 50 million people in 16 countries. And as we approach the end of the century, scientists warn that these extreme weather events could intensify and double in frequency.

On how to climb our way out of the 'new normal'

Brazil is not alone: extreme flooding has affected countries around the world.

El Niño-intensified Cyclone Hidaya has displaced thousands in Kenya and Tanzania. Floods sweep Indonesia's South Sulawesi. Dubai was underwater weeks ago. Pakistan saw its wettest April since 1961, with rainfall more than double the usual.

And it's also going in the opposite direction.

East Asia is grappling with a "brutal 48 C° heatwave". 48,000 state schools across the Philippines were closed, and "ruins of a centuries-old town have emerged at a dam parched by drought. A heat-induced explosion killed 20 soldiers in Cambodia. Myanmar is losing 40 people daily due to the heat. And "a long, hot summer is set to worsen conditions in Gaza."

Ugghhhh.

Covering climate change can feel like a constant stream of disaster reports. Sometimes, I feel like the pessimistic and catastrophic messenger. But this isn't a time for wallowing in doom and gloom. Brazilian president Lula is far from a climate activist but he is right: we need to stop running behind disasters. And the best (and only) way to do so is by embracing togetherness.

Together, we must create positive momentum. Incite change, spread awareness, and collaborate so that isolated efforts turn into a wave that rises relentlessly toward a better future. Because the truth is the next years are going to be rough: for every dollar you earn, climate change will charge you one.

This isn't about instilling fear or, worse, defeat; it's about preparedness.

Nature-based Solutions: The Real Answer

Budget constraints, regulations, and policies in water management, agriculture, and climate change mitigation are driving the necessity for sustainable, cost-effective solutions to flooding.

One answer lies in wetlands. Formerly seen as wastelands needing drainage, wetlands are now recognized as some of the most valuable ecosystems on Earth. They support biodiversity, filter pollutants, store carbon, and provide critical ecosystem services like watershed dynamics.

They are the natural solution.

Wetlands are water sponges. They trap and then slowly release water from rain, snow, ground, and floods. The trees and plant roots slow down runoff and spread it over the floodplain. In cities, wetlands counteract increased runoff from buildings and pavements. Riverine wetlands are particularly useful for storing and holding flows by retaining sediment and reducing excess sediment in the water — including peak flows that cause flood damage. Likewise, coastal wetlands prevent coastline erosion by absorbing energy from ocean currents that would otherwise destroy a shoreline and associated development.

Nearly 90 percent of the world's wetlands have been degraded or lost to date, and we are losing wetlands three times faster than forests. Over the past decades, the world has lost over 13,000 square kilometers of tidal wetland. However, we've seen gains of almost 10,000 km2 due to natural processes and large-scale ecosystem restoration activities. 27% of these changes relate to direct human activities like agriculture conversion and wetland restoration. The rest comes from indirect drivers, such as coastal processes and climate change. So, there's a lot of room for improvement here.

Floodplains and wetlands are cost-effective and eco-friendly solutions. They require minimal maintenance and are more environmentally friendly than cement dams or barriers, which harm local ecosystems and are far from a safe long-term solution.

There are success cases everywhere: the Dutch national plan 'Room for Rivers', in the Northeastern USA, River Skjern riverine wetland restoration in Denmark, Djegbadji Lagoon in Benin, Boracay Island in the Philippines, and even the Guapiaçu River Basin in Brazil. My country, Argentina resorted to this solution with success in Peninsula Valdes.

There's a lot of hope

Moving further, La Niña might provide some relief and halt our record-breaking climate streak. Wind and solar are 'fastest-growing electricity sources in history,' with powerhouse China leading the transition away from fossil fuels. And climate change is taking central pages of major platforms after decades of being misplaced.

This might be the longest uphill road humankind has ever faced, one we built for ourselves. But together, we can climb up the way out of this 'new normal,' one step at a time. Because it all comes down to compounding collective efforts.

Be loud.

Thank you for your thorough reading and support! And once again, much deserved credit and gratitude to Tim Smedley for his invaluable feedback. Subscribe for immediate insights and join the 400+ Antarctic Sapiens community for weekly thought-provoking content.