I love to tell people who come over to our place that the full-length mirror in the entry is one of the things we 'rescued' from our building's… waste store.

Other items include a cat tree, a small shelving unit, some cooking pots and a plant vase, all of which were in near-perfect condition.

Ever since our first rubbish find — which was the mirror — I look forward to going down there, hoping to find something else we could use. But although I've only become a trash panda recently, I always liked reusing stuff and had plenty of pre-loved items. Growing up, many of my clothes and toys were hand-me-downs as I was the youngest girl in my whole extended family.

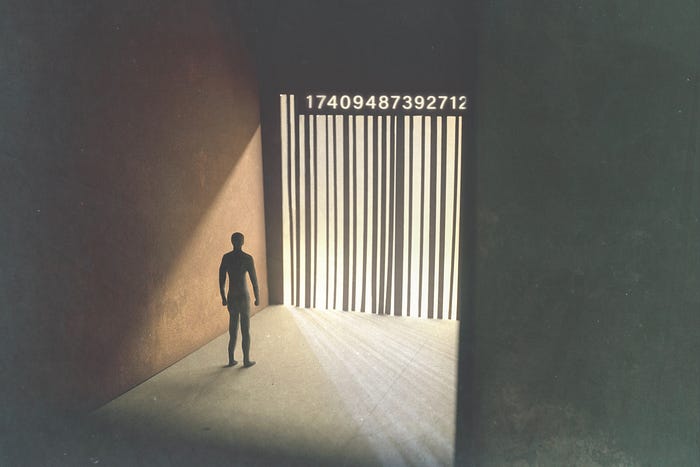

For years, including when I was a teenager — the mid to late 2000s — this wasn't exactly considered 'cool.' We were still largely enamoured with constantly buying new shiny 'stuff' and sold on the idea of what it supposedly means. (A better you. A happier you. A more successful you.)

Then things started changing. Slowly.

Well, to be fair, in some ways, unchecked consumerism might be worse than ever today.

But there also seems to be a growing awareness that, actually, you don't need to — and, more importantly, shouldn't — keep buying new shiny things all the time.

If there's one positive thing that came out of the COVID-19 pandemic and its restrictions on our usual activities, it's that it showed us simpler and less material lives are not only possible but could make us just as happy. If not more.

According to one survey done by Vox, which polled people from all around the world, the number one change they wanted to maintain after the pandemic was to reduce their consumerism. That included spending less on new material goods like gadgets and clothes and trying to 'mend and make do' instead.

In the years that followed, this started to be reflected in online trends and challenges aimed at reducing the number of things we buy, often referred to as 'Low-Buy,' 'No-Spend', or, most commonly, 'No-Buy' months or years. I've recently come across several 'No-Buy Year' viral videos — like this one, for instance — posted by people who plan on doing it in 2024.

The premise is pretty straightforward: abstain from buying any unnecessary new items — excluding essentials like groceries, medicine, toiletries, etc. — for the next twelve months. Or, in the case of people committing to do it just in January, for one month.

And although the motives behind this consumption detox are diverse, many overlap. Most commonly, people cite wanting to get their finances in order, stop living paycheck to paycheck, generate less waste and become more environmentally friendly. Some others who have tried the 'Low-Buy' lifestyle or challenge before also say it helps them find joy in things they already own and declutter their homes.

This fits in with the larger trend of the so-called 'deinfluencing,' which quickly gained momentum at the beginning of last year and, similarly to the 'No-Buy' one, discourages people from buying stuff they don't need or that isn't worth spending your money on. Some attribute its rise to the growing demand for authenticity online, but I think it also reflects the beginning of a shift from materialistic values towards greater consciousness about what we consume, how we consume it, and what it's doing to us and the planet we inhabit.

One recent study that examined over 440,000 YouTube comments from 2011 to 2021 found that there's been an increase in conversations about sustainable fashion, too, for instance.

Still, this is all sharply contrasted with the continuous glorification of traditional, hyper-consumerist influencer culture and the popularity of haul and unboxing posts that show people — which, worryingly, includes many minors — proudly bragging about buying dozens and dozens of products, often from ultra fast-fashion retailers like Shein or e-commerce giants like Amazon.

But, perhaps paradoxically, seeing consumerism at its worst might just be the thing that helps push more and more people to rethink their spending habits.

And it's not the only thing that could do that.

Amazon is actually no longer the most popular provider of shiny new things we love buying for momentary gratification. At least not according to e-commerce app rankings in some countries — the first place is now increasingly occupied by a Chinese platform called Temu, which is said to offer even more discounted prices than Amazon or Walmart.

It's no wonder why it's so popular, though. Thanks to a combination of inflation — or rather greedflation — and stagnant wages, more and more people struggle to make ends meet and look for the best bargain there is. Temu offers just that. And unsurprisingly, there's already been rumours that it sells goods using forced labour.

But here's the thing. While we tend to associate illegal, unsustainable and otherwise murky practices with low-priced platforms or brands, they are hardly the only ones that rely on them.

A couple of months ago, I wrote about celebrity brands like the Kardashian-owned SKIMS that, despite their hefty prices, are essentially fast-fashion wolves in seemingly more sustainable clothing. The same goes for many luxury brands that fall into an even higher price range. In 2023, nine luxury fashion companies that reported their emissions — including some of the biggest names in the sector, like Chanel and Prada — created over 13.5 million metric tonnes of CO2, roughly the same as the entire country of Lithuania. Created by nine companies. In just one year.

Whether a product has a low or high price tag, and particularly if it's not made from recycled materials (most still aren't), mining the materials for it, producing it and then distributing it to, first, warehouses and then stores or consumers comes at a high cost on both our planet and people.

All of this is one of the key reasons why only 3% of the world's ecosystems remain intact, why we're struggling with issues like air and water pollution and why we're living through a climate crisis. The unpleasant truth is that we're buying into our own destruction, and there's no way we could possibly consume our way out of it.

However, the good news is that thanks to decades-long efforts of environmental activists and researchers, there's indeed growing awareness of the problem. And that people are also waking up to the impact rampant consumption can have on us, the consumers.

We realise that despite the pleasure shopping can provide, it's fleeting. We realise that products advertised to us as 'must-haves' we can't 'miss out on' we'd probably forget about within a few months after buying. (One statistic, albeit old, included in Annie Leonard's 'The Story of Stuff' film states that just one per cent of 'stuff' is still in use six months after its purchase.)

We also realise that buying things doesn't make us better, happier or more successful. Actually, it's often quite the opposite: it clutters our homes, drains our savings accounts, and sometimes even creates consumer debt we struggle to pay off for years.

The latter is currently at an all-time high in countries like the US, the UK and possibly many more.

It's easy to get caught up in a cycle of consumerism.

But it's not always easy to get out of it.

Probably even more so today than, say, a decade or two ago, as many products aren't exactly built to last, and some are likely intentionally designed to become obsolete.

None of this is to say that the onus of responsibility falls on consumers and consumers alone. It's big corporations that decide to churn out mountains of products, often cutting corners whenever possible to increase their profits, and then try to push as many of them down our throats as possible.

Still, the cold fact remains that it's 'developed' countries that consume the most. It's been suggested that if everyone consumed as much as the average American, we would need 5.2 planets to support us. The number is three if everyone lived like the average Japanese and about 3.3 as Europeans.

But we also aren't as powerless as we might think. Individual actions can become social trends that eventually make a difference.

Adopting a 'No-Buy' challenge and restraining ourselves from buying unnecessary things for some time while re-assessing the items we already own seems like a good place to start. Still, we need a far bigger shift in our relationship with consumption in the long run.

One thing that works well in the community where I live is having group chats where people can swap, sell or give away items they no longer have use for. Every day, hell, almost every hour, there are people doing just that. Some even try to barter and offer cooked meals or expertise in exchange for something they need. Some others who run small businesses also sell their products.

Another thing is to pay more attention to what we already own and try to repair it if it breaks. But, unfortunately, this is often easier said than done. Not only there aren't as many repair shops as there used to be — there's virtually none in a 5-mile radius from me, and I live in a big city — but some manufacturers actually restrict the availability of spare parts or tools, making it even more difficult to fix broken items.

But this just ties back to the reality of a highly-consumerist, capitalist society.

'Stuff' isn't meant to be repaired or last.

It's meant to keep piling up in our houses — which some also hoard to the detriment of society, but that's a whole other story — while we keep buying more and more and more and more.

At some point, humanity will have little to no other option but to reuse what we've already produced for the simple reason that, well, physics exists.

We can wait until the moment we're literally choking on and drowning in our own waste or stop buying into the myth that consuming ourselves into oblivion is the key to happiness, well-being or, bizarrely, the backbone of society.

The idea that consumption is good because it drives economic growth and economic growth is good because it 'trickles down' fails to take into consideration one crucial aspect: our lives are entirely dependent on complex natural systems we're currently burning up in a final frenzy dedicated precisely to the Gods of Economic Growth.

So, yes, it could do us good to re-evaluate our relationship with material goods. And, ideally, stop being obsessed with them so much.

None of us are taking them to our graves.

Or the afterlife if you believe in it.

If you like my work and want to support it, buy me a cup of coffee. For more of my content, subscribe to my Substack newsletter or check out my other social media platforms.