On the east bank of the Nile in Luxor, two monumental temples stand as testaments to the grandeur and spirituality of ancient Egypt. The sprawling Karnak Temple Complex and the elegant Luxor Temple were not just places of worship. They were centers of power, ceremonies, and divine connection. For centuries, these temples united gods, kings, and people in their pursuit of ma'at — the cosmic balance that sustained Egypt.

Karnak: The City of Amun-Ra

Karnak is awe-inspiring in its sheer scale. Covering more than 200 acres, it is the second-largest religious complex in the world, surpassed only by Angkor Wat in Cambodia. Over 2,000 years, generations of pharaohs added to Karnak, transforming it into a sacred city dedicated to Amun-Ra, the sun god, and his divine family, Mut and Khonsu.

The Great Hypostyle Hall is the jewel of Karnak. It feels like stepping into a forest of stone. Its 134 towering columns, arranged in 16 rows, create a space of overwhelming majesty. The central columns rise to nearly 69 feet, their capitals shaped like papyrus blooms — symbols of creation and life. Every surface is alive with hieroglyphs and reliefs. Pharaohs kneel before the gods. Battles are won. Prayers are offered. The light filtering through the gaps between columns creates patterns that make the carvings seem to move, almost as if the stories are still unfolding.

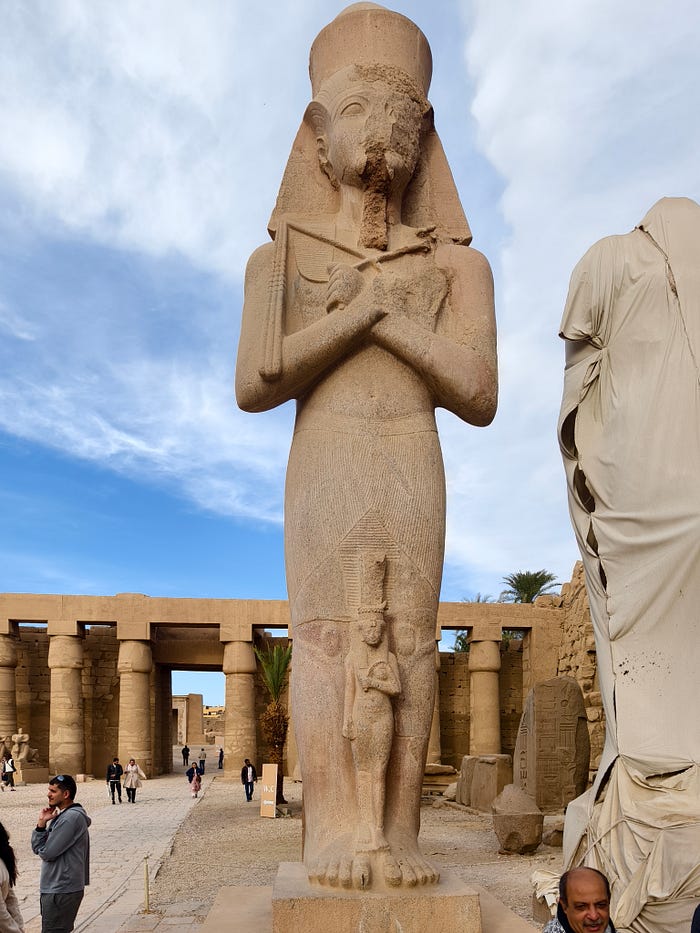

Elsewhere in Karnak, Hatshepsut's obelisk rises nearly 100 feet into the sky. Ramses II stands in colossal form near the Second Pylon, with Queen Nefertari depicted at his side. These statues and monuments were declarations of devotion to the gods and reminders of the pharaohs' divine authority.

Karnak's Sacred Lake adds to its mystique. This vast, tranquil body of water was used by priests for purification rituals. Nearby, a granite scarab stands as a symbol of rebirth. Even today, visitors walk around the scarab seven times, hoping to bring luck and blessings into their lives.

Luxor: A Temple of Kingship and Transformation

Luxor Temple, smaller than Karnak but no less magnificent, was dedicated to the renewal of kingship. Built primarily by Amenhotep III and Ramses II, its purpose was to honor the pharaoh as the living embodiment of the divine. The temple stands as a masterpiece of balance and elegance.

The entrance is dramatic. Two colossal statues of Ramses II flank a towering pylon, with one of the original obelisks still standing tall. Its twin now resides in Paris, gracing the Place de la Concorde. Inside, the temple opens into courtyards, hypostyle halls, and sacred sanctuaries. Every space tells a story. Reliefs show Ramses II being crowned by the gods, reaffirming his divine right to rule. The carvings depict fertility, prosperity, and the strength of the Nile's inundation.

For centuries, Luxor Temple lay buried halfway under the sands. Homes and markets were built over it, concealing its grandeur. In the 19th century, archaeologists unearthed the temple, revealing its towering columns, intricate carvings, and ancient secrets. Yet even during this time of obscurity, Luxor retained its sacred aura. The Mosque of Abu al-Haggag, built in the 13th century, rose atop the temple, its minaret still standing proudly. Earlier, Coptic Christians had converted parts of Luxor into a church. Roman emperors added their touch, with chapels dedicated to Augustus and later rulers. Today, Luxor Temple is a tapestry of faiths and histories, blending Egyptian, Christian, Islamic, and Roman influences.

The Opet Festival: Divine Renewal

Karnak and Luxor came alive each year during the Opet Festival, a celebration of renewal and cosmic harmony. The festival began at Karnak, where statues of the Theban Triad — Amun, Mut, and Khonsu — were placed on golden barques and prepared for their sacred journey. Carried by priests along the Avenue of Sphinxes or floated down the Nile, the statues were transported to Luxor Temple.

At Luxor, rituals in the temple's birth-room ensured the pharaoh's rebirth as the son of Amun-Ra. This rebirth wasn't just symbolic. It reaffirmed the pharaoh's role as the mediator between the gods and the people. It also promised fertility for the land, prosperity for the Nile's inundation, and a continuation of the royal lineage. For ordinary Egyptians, the festival was a time of joy and celebration, with music, dancing, and offerings accompanying the gods' procession.

Alexander the Great and the Ptolemies

By the time Alexander the Great arrived in Egypt in 332 BCE, Thebes already had a history stretching back two millennia. Alexander, raised on tales of Homer's Iliad, admired Egypt's grandeur and sought to align himself with its traditions. Declared the son of Amun at the Oracle of Siwa, Alexander became a pharaoh in the eyes of the Egyptians.

At Luxor, Alexander left his mark with a barque chapel inscribed with his name in royal cartouches. Depicted in Egyptian attire, he stands before Amun, presenting himself as the god's chosen ruler. Remarkably, this chapel was built within an older structure constructed over a millennium earlier. The overlapping walls, one shrine within another, symbolize the continuity of kingship and divine favor.

The Ptolemies, Alexander's successors, continued to revere Luxor and Karnak. These temples remained central to Egyptian religious life, their ceremonies reinforcing the connection between the gods, the land, and the ruling dynasty.

The dance of power

As majestic as the temples of Karnak and Luxor were, they also became centers of immense political power through their times. By the time of the New Kingdom, the priesthood of Amun-Ra had grown so influential that up to 20% of Egypt's tax revenues were directed to the temples. With their vast wealth, sprawling lands, and control over religious rituals that affirmed the pharaoh's divine authority, the priests of Amun were becoming political forces in their own right.

This growing friction came to a head during the reign of Pharaoh Akhenaten (1353–1336 BCE). Akhenaten attempted a radical experiment to curb the power of the Amun priesthood by introducing Aten, the sun disk, as the sole deity. Moving the capital to Akhetaten (modern-day Amarna), he sought to establish a monotheistic religion centered around Aten and himself as the sole intermediary. Some claim that the cult of Aten was not monotheistic, but he was created to only take on Amun-Ra, the central God of both Karnak and Luxor.

The experiment unraveled after Akhenaten's death. His successor, Tutankhaten, only a boy when he ascended the throne, was pressured to abandon his father's controversial reforms. He changed his name to Tutankhamen, aligning himself once more with Amun-Ra, and moved the royal court back to Thebes. The temples of Karnak and Luxor regained their central role in Egyptian religion and politics, and the glory of the Amun priesthood was restored.

This brief episode of turmoil highlights the delicate balance between religion and state in ancient Egypt. Karnak and Luxor, though built to honor the gods, were also deeply entwined with the pharaoh's authority. Their grandeur symbolized the divine connection of the king, but their power could also challenge it.

— -

In the Egypt series:

- Gods and Kings: How they shaped Egyptian ethos

- Whispers of eternity: Walking amongst the pyramids of Egypt

- A Sacred Marriage: How Karnak and Luxor Cemented Egypt's Cosmic Order

- Valley of Kings, Temple of Hatshepsut, and Valley of Queens

- Kom Ombo and Edfu: Temples of Duality and Power

- Philae: An island of Gods and Legends

- Moving mountains: The legacy of Abu Simbel

- The Citadel of Saladin: Cairo's Guardian through the ages