Ancient Egypt

"If you want to move people, you look for a point of sensitivity, and in Egypt nothing moves people as much as religion." — Naguib Mahfouz

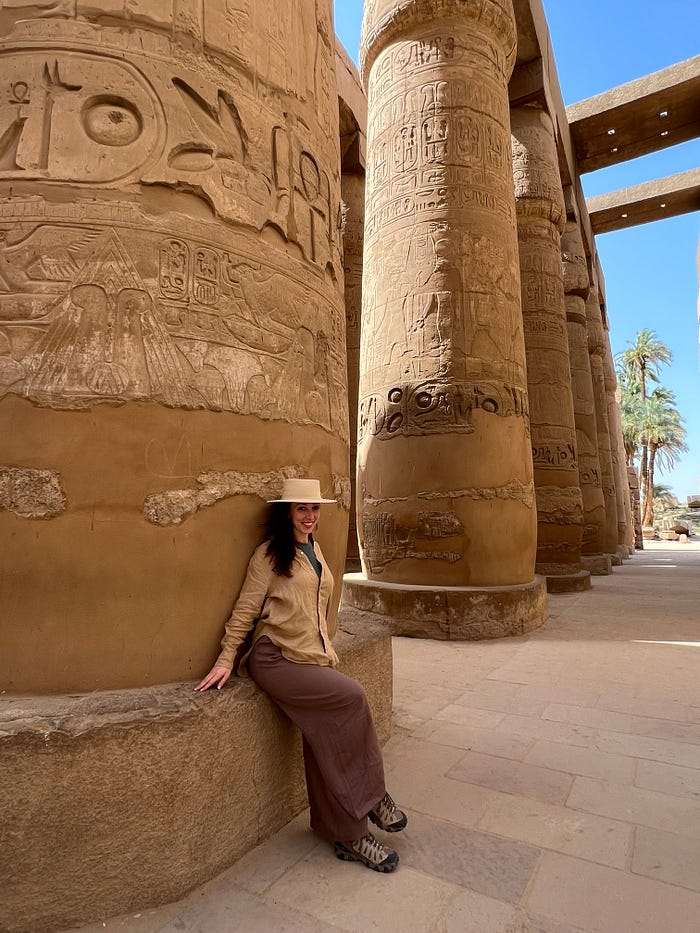

Like many travelers before us, my friend and I flew to Egypt to see the Great Pyramids. But further south, in the city of Luxor, there are other great wonders beneath the surface. I speak of the tombs.

These places are shockingly colorful. They pit your wonder against your ability to endure the desert heat. You think the descent into the earth to explore will take you someplace cool as a cave, but no. It gets warmer. Sweat slips down your body while crowds slip by you. Guards bother you with basic facts and flirtation in the hope of tips. But don't worry. The wonder of Ancient Egyptian tombs is enough to keep you underground.

These expansive tombs hold an astonishing amount of hallways, rooms, and chambers. Every wall is complexly painted, floor to ceiling, in Ancient Egyptian concepts. Inside them, you pass by beast-headed gods and goddesses — hieroglyphs — pictures of the dead — and more, over every inch. Except the ceilings. Those are usually painted with golden night stars on smooth dark blue.

All the tombs are mind-boggling. That's true even of the relatively humble tomb of physically tiny King Tutankhamen.

If you want to know how standing in an ancient Egyptian tomb feels, listen to Siouxsie and the Banshees' music. For me, that music and those tombs elicit similar feelings: feelings eerie, distinct, evocative, and mystical, yet still, of the senses.

But among all the wondrous tombs in Egypt, only one touched my heart.

The Tomb of Nefertari alone brought a tear to my eye. You'll need to see it with your mind's eye and know some of the history behind it to know why.

Know that it was her husband who built her tomb. History interprets this husband as very in love with her. Among many other things, he built her this particularly lavish resting place. It is even uncommonly located close to his own, for a king. You'll recognize the man's name: Rameses. And yes, we're talking about the most famous one.

To quote Wikipedia:

"Rameses II, commonly known as Ramesses the Great … is often regarded as the greatest, most celebrated, and most powerful pharaoh of the New Kingdom, itself the most powerful period of Ancient Egypt." — www.wikipedia.org

Nefertari was greatly loved by a great man. That is how it seems.

In your mind's eye, come with me now. See the bright colors on Nefertari's walls, even after these thousands of years! Her resting place is more colorful and better-preserved than perhaps any other tomb or temple yet uncovered.

There was one archway that stopped me in my tracks. It even drew me back again and again. Queen Nefertari stands painted as tall as me inside of the doorway. Directly opposite on the other interior side is her mirror image, but in this one, she is crying.

Her coffin is no longer in her tomb. In fact, modern Egyptologists only found her mummified legs — these, and the pink granite shards of her once-dazzling sarcophagus. In the tomb's back room, there is a giant recess in the floor that cradled the sarcophagus in its center. You can walk around the space today.

I don't know what connotations pink had for Nefertari, her personal relationships, or her people. But for me, a pink granite tomb reinforces the feeling of Rameses's lighthearted devotional love — and of course, of her femininity.

Consider this. The beautiful tomb, built for a woman by her husband, has no paintings I could discern of said husband. The walls display Nefertari living out scenes from the Book of the Dead (as befits any ancient Egyptian burial site). The Queen's companions walk with her, hand in hand, through the afterlife. They stand by her side from death, through judgment, to reincarnation. And they are all women.

Are they goddesses? Priestesses? Personal friends? My ignorant traveler's eye doesn't know. Whoever they were, they were caring.

Osiris — his green skin representing life — is pagan Egypt's god of the underworld. His lone figure appears again and again through her tomb, as well. He is serious and regal in every depiction. Despite this, in her tomb, he also looks like a benign man.

I began to picture Nefertari, alive, visiting this place as it neared completion. She would have looked at all these paintings. I think both the women walking with her, hand in hand, and Osiris' regal repetition were ways of helping the real, living Nefertari come to terms with death. But, in as reassuring a manner as possible.

Maybe the queen had a particularly acute fear of death. Maybe her husband knew this. All humans dread their mortality at some time or another. But perhaps she was one of us who particularly fixates on it, and is scared. Maybe even the fact she was famously beautiful heightened her fear of decay. The greatest of us fall further, after all.

When I understand this tomb as a present from her husband, I am touched. Really, fellow traveler, it is particularly beautiful and well done. Some historians even call it The Sistine Chapel of Ancient Egypt!

Seeing the absence of paintings of the man himself, yet the presence of so many female guides to Nefertari as she traversed the after life — this also touched me. She had sisterhood. Rameses wanted her to have it.

If my theory is correct, this tomb was aimed to comfort Nefertari. Selflessly, on the part of Rameses. He doesn't "put himself in the picture" anywhere. Instead, the pictures show so many women cherishing and caring about her. They walk with her past death, through judgment, and on to her reincarnation.

Ancient Egyptians believed you only reincarnated if you had a proper burial. I grin. This tomb is so unique, so perfect, so elaborate. The mirror images of Queen Nefertari in the arched doorway, smiling and crying. The familiarizing repetition of Osiris, God of the Dead. The pink granite sarcophagus, the female friends holding her hand through it all, the drenching of hieroglyphics everywhere.

I imagine Nefertari's carefully-done tomb was one more of her husband's ways of saying, "I love you, and I want us to do this again."

I walked through what modern society would call her resting place. But her people understood it as her transitioning space.

It's a place of comfort, beyond a standard place of ancient rites.

More importantly, it is a place of love — both the love of a spouse and the love of women for each other.

It is a monument to the belief that love can conquer death.