The man in the center of the Chinese propaganda poster will be instantly recognized by many people around the world. But unless you are familiar with the history and political culture of the People's Republic of China you might miss the more subtle messages embedded in this image.

In our current age of pervasive political disinformation, we all need to develop skill in recognizing and decoding propaganda.

I spent three years in the PRC in the mid-1980s. Before I went there, I studied Mandarin and symbolic politics as part of a doctoral program in cultural anthropology. I wanted to understand how state propaganda works and could think of no better place to see propaganda in action than China.

Before I describe some of what I learned about propaganda from the time I spent in China and from research after, let me offer a brief reading of the image at the head of this essay — a detail of a poster I picked up in a bookstore in Changchun, Jilin Province in 1985.

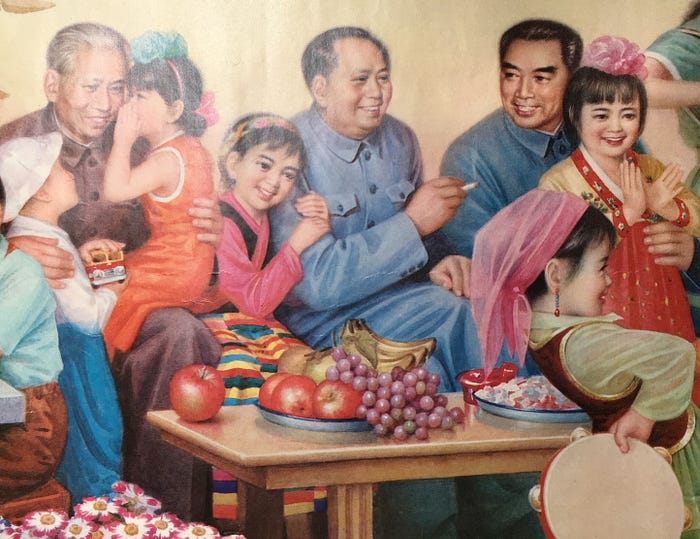

The poster was designed as a colorful decoration for a wall in an elementary school classroom or for display in a Chinese family home. It depicts three founding fathers of the Chinese Communist Party and state, Mao Zedong in the center, Zhou Enlai on the right, and Liu Shaoqi on the left.

At first pass, the message of the poster is obvious. Three paramount leaders of China are surrounded by happy children in a festive scene. It's an image of peace and prosperity and security. Everyone appears to be having a good time. Leaders and children alike look happy, relaxed, and well-fed.

The image says: Life in China is good because Uncle Mao, Uncle Zhou, and Uncle Liu (and the Chinese Communist Party State) made it so. But this is just a superficial reading revealing only the most obvious propaganda purpose of the poster.

Peeling the Propaganda Onion

To get at deeper levels of meaning embedded in the image requires a closer look at some of its details and some background knowledge. Why were these three men placed at the center of this party scene? Who are those children with whom they seem to share such apparently strong bonds of affection?

The children cavorting blissfully in the company of Uncle Mao, Uncle Zhou, and Uncle Liu are dressed in colorful costumes. Those costumes are meaningful.

In the U.S., we sort people— albeit unreliably and unscientifically — into different racial and ethnic categories based on visible traits such as skin tone, facial features, and hair color and texture. In the P.R.C., differences between Han Chinese and non-Han Chinese "minority nationalities" (xiaoshu minzu) are marked by traditional styles of dress.

The girl hugging Mao's arm is wearing a Tibetan-style dress. The girl being held by Zhou is wearing a Korean-style dress. The girl whispering in Liu's ear is wearing a Han-style dress and the boy at his knee wears what a Chinese viewer in the 1980s would have seen as modern, western-style clothing typical of urban-dwelling Han Chinese. The girl dancing in the foreground is wearing an earring, a head scarf, and a vest and is holding a tambourine, all things associated with the Uyghur nationality.

Decoding the children's costumes reveals a slightly deeper reading of the propaganda poster: The Chinese Communist Party and the leadership of the P.R.C. are protecting and ensuring the mutual respect and prosperity of the all the peoples of China, Han and non-Han alike.

There is a third layer of meaning of this poster, perhaps its most important. It comes from the juxtaposition of the three men at the center of the image and, specifically, from the inclusion of Liu Shaoqi alongside Mao and Zhou in this tableau of Chinese Communist Party demi-gods.

When the poster was designed and distributed in the early 1980s, Liu, Mao, and Zhou were all dead. The stories of their deaths go a long way toward providing the background needed to understand the political significance of the poster in the context of Deng Xiaoping's leadership in the Four Modernizations era (announced by Zhou in 1975, officially initiated by Deng in 1978).

Mao and Zhou both died in 1976. Their deaths marked the beginning of the end of the Cultural Revolution. When Zhou died in January 1976, a ban was imposed on public expressions of mourning for fear they would morph into protests against the political extremism and turmoil of the Cultural Revolution. The ban was conveyed to the masses via the "five nos" campaign (no wearing black armbands, no memorial halls, no funeral wreaths, no memorials, and no handing out photos of Zhou).

Zhou had been ill with cancer and out of the public eye for some time before he died. During his illness, Vice-Premier Deng Xiaoping had taken on many of Zhou's roles and responsibilities in the Politburo.

Even before Mao died in September 1976, mass gatherings and public grieving for Zhou in violation of the "five nos" revealed the depth of public disaffection with Chairman Mao and with the Gang of Four who had lead China into the chaotic depths of the Cultural Revolution at Mao's direction. In April 1976, an estimated two million people visited Tiananmen Square in Beijing to pay their respects to Zhou Enlai in appreciation of his reputation (whether deserved or not) as a force for moderation of the excesses of Mao and the Gang of Four.

After Mao's death, the Gang of Four lost power and Deng Xiaoping consolidated his control of the party and state, ending the Cultural Revolution and initiating the Four Modernizations era.

Liu Shaoqi was arguably the most prominent of the political victims of the Cultural Revolution. Liu had been a close comrade and confidant of Mao from the very start, joining the Chinese Communist Party in 1922 and quickly rising in the ranks of CCP leadership.

In 1959, Liu took over Mao's position as President of the P.R.C. — Mao retained power as Party Chairman and head of the Chinese Army — a move necessitated by the need to create distance between the Chinese State and the mass starvation caused by Mao's Great Leap Forward. In the early 1960s, Liu, with help from Deng Xiaoping, implemented market-based reforms to help restore the Chinese economy.

After Mao announced the start of the Cultural Revolution in May 1966, nearly all senior CCP leaders who had been critical of Mao, including Liu and Deng and their families, became targets for the Red Guard. By 1967, Liu and his wife, Wang Guangmei, were under house arrest. In November 1969, Liu died in prison. News of his death was not reported until 1974.

In 1980, as part of Deng Xiaoping's consolidation of party and state control, he restored Liu's reputation and status as a founding father of the People's Republic of China.

So here is the deepest political message embedded in the propaganda poster: Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai were great leaders, but not infallible; Liu Shaoqi was right to criticize the political excesses of Mao and help put China on the path of modernization and prosperity.

How to Recognize and See Through Propaganda

I think my time living in the People's Republic of China in the 1980s has helped me recognize propaganda more easily and to read it more deeply than most folks.

As I see it, the United States is currently awash with political propaganda — primarily produced by the extreme right-wing and inspired by MAGA anti-democratic populism. Disinformation is so pervasive it threatens to drown out reasoned political debate and could very well usher in an era of autocratic rule.

Back in early 2020, I started noticing that I was seeing propaganda coming from the White House that reminded me more and more of the propaganda I had been exposed to in the P.R.C. At the time, I published an essay on Medium discussing the Trump administration's frequent use of one of the most powerful tools in the propaganda toolbox, the "big lie," a tool perfected by the Nazi regime under Hitler and also used extensively in China and by autocrats elsewhere.

The basic principle of the "big lie" is that people will tend to believe a big lie, if it is repeated frequently, more readily than a small one. Trump and his supporters have used the "big lie" consistently and effectively, nowhere more so than in the claim that the 2020 election was "stolen."

One way to recognize propaganda and to separate disinformation from facts is to consider the feelings a political image or piece of news is intended to evoke. Propaganda is almost always designed to elicit a strong emotional response.

The feelings propaganda evokes are often one or more of the following four:

- Fear of missing out — Propaganda uses the "bandwagon" effect to encourage feelings of belonging, for example, the inclusion of children representing different minority nationalities in the Chinese poster or pictures from a Trump rally showing happy people in MAGA hats.

- Fear of "others" — Propaganda uses "scapegoating" to evoke fear and anger, for example, describing migrants as "poisoning the blood" of America and making jokes about organizing a "migrant fight club."

- Paranoia — Propaganda uses ill-defined threats to evoke uncertainty and doubt, for example, playing on fears of violent crime and distorting or fabricating crime statistics and trends in an effort to stoke distrust of leaders of "Democrat-run" cities.

- Hope — Propaganda uses "glittering generalities" to evoke feelings of nostalgia and well-being, for example, portraying dictators as avuncular and benign in a surreal party scene as in the Chinese poster or promoting vacuous slogans like "America First" or "Make America Great Again."

By evoking one or more of the above emotional responses, propaganda gets in the way of clear thinking and creates confusion and doubt. In this way, propaganda works to make people malleable and more easily convinced to accept the alternative to truth conveyed by the propagandist.

Recognizing propaganda is the first step in reducing its impact, on ourselves and on others. Uncovering the hidden intent, the emotional force, and the distortions and lies embedded in propaganda is the second step.

As I illustrated in my "decoding" of the Chinese poster, uncovering the more subtle messages conveyed through propaganda can require some knowledge of the political context in which the propaganda is used as well as the goals and interests of the political actors the propaganda is intended to serve.

Earlier this this year I happened to be in the home of a relative in Missouri whose television was tuned to the One American News Network. Though the sound was turned down and I did my best to ignore the television, I was unable to avoid noticing that a short video clip was being played over and over again in a loop. This kind of repetition is a clear sign of propaganda.

The video clip — no more than 30 seconds long — was of an incident I recalled having been in the news in the Bay Area several years earlier. It showed a young man who appears to be Black riding a bicycle through the aisle of drugstore while sweeping items off shelves into a bag and then riding out the door past a security guard who does not stop him. The surface message of this bit of propaganda is that crime is out of control.

The emotions the repetition of the video clip was designed to evoke included anger and fear of the young Black man on the bike and perhaps even deeper anger and disgust aimed at the security guard for not intervening to stop the theft. By triggering these emotions, OAN was making it difficult for its viewers to think clearly in evaluating right-wing demands for more aggressive law enforcement. This bit of propaganda was also intended to heighten viewers fears of crime by reinforcing racist associations of criminality with Blackness.

For me, uncovering the lies and distortions in the video clip was made easier by my knowledge of its background and original context. First of all, the clip was several years old, hardly the stuff of late-breaking news. Secondly, the incident shown in the video was originally deemed newsworthy because it was so unusual. America is not, as the OAN repetition of the video clip implies, plagued by an epidemic of bike-riding shoplifters.

Fighting MAGA Propaganda Requires All Hands on Deck

As extreme right-wing propaganda efforts in America continue to scale up, countering those efforts will take a massive response. Organized efforts to debunk and stop the spread of political disinformation in the U.S. have been weakened by sustained attacks by right-wing politicians. Republican members of the House Judiciary Oversight Committee recently celebrated the demise of the Election Integrity Partnership —a research organization that provided rapid responses to political disinformation — as a "big win."

The time for complacency is long gone. MAGA propaganda is powerful and it will succeed in seducing many Americans to follow their fears and vote against their own best interests.

The threat of right-wing authoritarian rule is real. All Americans who care about preserving the integrity of our electoral process need to learn to recognize propaganda and to call out its lies and distortions.